- The Intrinsic Value Newsletter

- Posts

- 🎙️ TSMC: The Most Important Company in the World?

🎙️ TSMC: The Most Important Company in the World?

[Just 5 minutes to read]

“Taiwan Semiconductor is one of the best-managed and most important companies in the world. And I think you’ll be able to say the same thing 5, 10, or 20 years from now.”

This is what Buffett said about TSMC in his 2023 shareholder meeting. However, he added, “I don’t like its location.”

That one comment may explain why Buffett exited his $5 billion position in TSMC just a few months after initiating it, despite praising the business itself in the strongest terms.

Since then, the stock has more than doubled. But the geopolitical noise surrounding Taiwan hasn’t quieted down. So today, let’s take a closer look at TSMC and whether the quality of its business can outweigh the risk of owning it.

After visiting Brazil in our Nubank post last week, this week we are making a trip to the next country we haven’t yet visited – Taiwan!

— Daniel

*Last Announcement*

A few weeks ago, we announced that we’d open 30 spots for our Intrinsic Value Community — and the interest has genuinely blown us away. We’ve spent a lot of time reviewing applications and continue to do so carefully.

The Intrinsic Value Community is a place for sophisticated, long-term investors to exchange ideas, challenge each other’s thinking, and build meaningful connections with like-minded individuals.

We give each other feedback on our research, share high-conviction ideas, and host guest speakers, from industry insiders to seasoned investors, who walk us through their strategies, investments, and mental models.

Today is your last chance to apply for this cohort. A handful of spots are still available, and we’ll carefully review every application we receive — that’s a promise! So, if you want to join, now is the time!

TSMC: The Most Important Company in the World?

Taiwan — Becoming the World’s Semi Factory

Before TSMC was founded, no one, not in their wildest dreams, could’ve imagined that Taiwan would become the epicenter of the most advanced manufacturing in the world.

Back then, Taiwan was known for its labor-intensive, low-cost industries. Western companies went there to produce textiles, plastics, and basic electronics on a large scale at a low cost. Fast forward to today, and the companies knocking on Taiwan’s door are Apple, Nvidia, and Google.

So, why did this transformation happen — and perhaps more interestingly, how? The why is relatively straightforward. By the 1980s, Taiwan’s low-cost advantage had begun to fade. Rising wages and lower-cost competition from China and Southeast Asia pressured Taiwan to move up the value chain. That strategic shift set the stage for TSMC’s founding in 1987 and Taiwan’s transformation into a high-tech powerhouse led by semiconductors.

TSMC’s history is a story worth telling on the big screen. There’s no movie about it yet, or about its founder, Morris Chang, but I wouldn’t be surprised if that changes one day.

Morris Chang was born in China, educated at Harvard and MIT, and with 30 years of experience in the industry at Texas Instruments, Chang had seen the entire semiconductor value chain from the inside. But when he was passed over for the CEO job at TI, Taiwan came calling. The government aimed to establish a world-class semiconductor industry, and it tasked Chang with building it.

What seems like a no-brainer in hindsight was a massive leap into the unknown at the time. Instead of becoming CEO of a well-established semiconductor firm, ideally in the U.S., Morris Chang found himself starting from scratch in a country known for manufacturing textiles and plastics, not cutting-edge semiconductors.

But at 56 years old, with no clear path to a top leadership role at any of the industry giants, he took the offer. And under his leadership, TSMC would go on to revolutionize the global semiconductor industry. What he proposed was unknown at the time: a “pure-play” foundry. A company that would manufacture chips for others but not design any itself. At the time, every major chipmaker controlled both design and production. No one outsourced critical IP to a third party.

TSMC — The Unbeatable Value Proposition

Before we go further, I should explain the difference between designing and manufacturing a chip. Think of designing a chip as creating its blueprint.

That blueprint tells the chip what to do – how to process information, store memory, or power graphics – kind of like planning how all the parts of a car engine will work together. Once that blueprint is ready, a manufacturer like TSMC steps in to turn that blueprint into reality, layer by layer, on a piece of silicon.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the dominant players — Intel, Texas Instruments, and IBM — all followed a vertically integrated model, designing and manufacturing their chips in-house. While this approach worked well for large, diversified companies, it came with trade-offs. Innovation slowed, and as semiconductor complexity grew, costs surged.

Design teams were often limited by internal manufacturing roadmaps, while manufacturing units were under constant pressure to maintain high utilization, even when demand was low. TSMC broke that cycle by focusing solely on manufacturing. By offloading production, fabless companies like Qualcomm, Broadcom, AMD, and today, more than ever, Nvidia and Apple, were free to focus entirely on design.

Charlie Munger once said that in the modern world, specialization is rewarded, and TSMC leveraged that specialization like no one else. What made this model unstoppable was the scale advantage it created.

Semiconductor fabrication is among the most capital-intensive businesses on earth. A single advanced fab can cost more than $20 billion, and both TSMC and Samsung have been spending over $30 billion annually in capex to stay at the cutting edge.

TSMC – Orange Line; Samsung – Blue Line

TSMC, by aggregating demand from dozens of customers, could run these fabs at a higher utilization rate than its integrated competitors. This gave it a cost advantage, which it reinvested in more advanced nodes, improved process yields, and tighter integration with its customer roadmaps.

Over the past five years, its return on incremental invested capital (ROIIC) has averaged in the mid-30s — an exceptional figure for such a capital-intensive and cyclical business.

By now, you already know where this is going…

It’s TSMC’s flywheel. A self-reinforcing loop of competitive advantages that compound over time. This is what built the company’s moat and turned it into the undisputed champion of semiconductor manufacturing.

As we discussed in our podcast, dominating the semiconductor industry for decades is an incredibly challenging feat. It’s notorious for its fast pace and innovation, which is not a great environment for becoming a long-term market leader. TSMC did it anyway.

More volume means lower cost. That’s true in many industries, but in semiconductor manufacturing, where capex runs into tens of billions, it’s even more important. As the world’s leading semiconductor manufacturer, nobody has more volume than TSMC. It controls roughly 60% of global foundry revenue and over 90% at the leading edge (5nm and below).

Speaking of the leading edge, let me briefly explain the difference between the different sizes of nodes. Semiconductor nodes refer to the size of the transistors on a chip, measured in nanometers (nm).

The smaller the node, the more transistors can be packed onto a single chip, which generally translates into better performance and greater energy efficiency. TSMC’s most advanced nodes (5nm, 3nm, and soon 2nm) are used in performance-critical applications like smartphones, high-performance computing, and AI accelerators. Key customers include Apple, Nvidia, and AMD.

iPhone sales have stagnated for years, though, and with Apple being one of TSMC’s largest customers, this was a key reason for the slowed growth in that segment.

That didn’t stop TSMC, though. High Performance Computing has consistently grown and is now 51% of TSMC’s revenues. In 2024 alone, TSMC’s revenue from AI-related chips more than tripled, and for 2025, it’s expected to double again.

More mature nodes (like 28nm or 65nm) are still widely used in sectors such as automotive, industrial, and IoT applications, where reliability and cost efficiency matter more than cutting-edge performance.

Even those historically less important sectors are becoming increasingly important. Automotive revenue has outpaced smartphone growth by two to three times in recent years. While most of that demand still relies on mature nodes, the shift toward autonomous driving and software-defined vehicles is pushing more of it toward the leading edge.

Companies like Tesla, Waymo, and even traditional automakers like Mercedes-Benz are becoming increasingly valuable customers.

Growth — Fueled by the AI Revolution

As demand for high-performance computing (HPC) and AI accelerators surges, TSMC has emerged as the single most crucial manufacturing partner for the companies driving this revolution.

Virtually every AI chip that matters today, from Nvidia’s H100 and B200 to AMD’s MI300X, is fabricated by TSMC. The company’s mastery of ASML’s extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography and ability to scale leading-edge nodes made it the go-to manufacturer for all ship designers.

Nvidia’s CEO, Jensen Huang, is not holding back when talking about TSMC’s importance for Nvidia and the entire AI industry. When asked if he has any intentions to reduce Nvidia’s dependency on TSMC, he was quite explicit:

“No! The reason why we depend on TSMC is because they’re the world’s best. And they are the world’s best not by a little a bit. They’re the world’s best by a mile. It’s incredible how good they are at what they do. And it’s not just technology. It’s technology, it’s scale, but it’s also the deep trust that we have. TSMC is just truly extraordinary.”

Between 2019 and 2023, TSMC doubled its revenue from $35 billion to over $70 billion, driven by the rising complexity of semiconductors and the shift to advanced nodes. Nodes measuring 7nm or smaller account for 70% of revenues. That’s not only an advantage because they carry higher margins, but it’s also important because very few other players even compete in that segment. That’s why all the demand goes to TSMC.

We’ll talk about why exactly TSMC is the undisputable champion in this space in a minute. Before that, let’s quickly look at the growth outlook once more.

According to TSMC’s management, AI-related semiconductors currently make up a mid-single-digit share of total revenue, but that’s changing quickly. They expect this figure to grow at a 50% compound annual rate, reaching around 20% of total revenue within the next five years.

And as mentioned earlier, while automotive and IoT are still relatively small segments, they are growing rapidly and account for 7% and 9% of 2024 revenue, respectively. Even companies you would never expect become TSMC’s customers, diversifying TSMC’s operations and thereby reducing cyclicality. John Deere, for example. A producer of farming equipment and one of the first companies covered on our show.

Turns out, even tractors are high-tech machines now.

The Competitive Edge — Why Nobody Else Can Do It

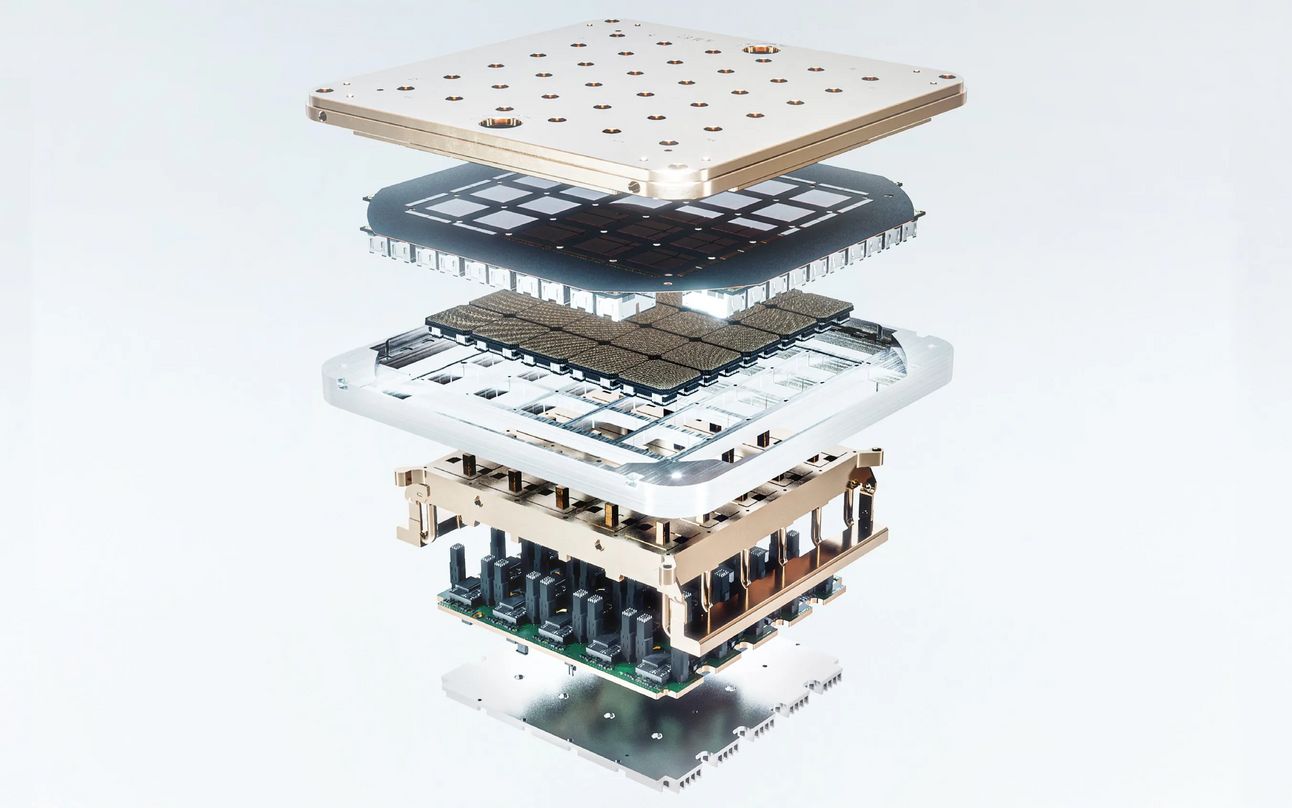

The process of manufacturing wafers is among the most complex in the world. Start with process know-how. Producing a single 3nm wafer means guiding it through hundreds of ultra-sensitive steps: lithography, deposition, etch, clean, repeat. Each of these steps has thousands of variables.

This process involves a lot of trial and error, and TSMC has gained decades of experience in it as a pure-play foundry, processing tens of millions of wafers per year. When a new company enters the market, they can buy the machines (although, as we will see, even that is difficult), but they can’t buy the know-how.

Perhaps that sounds a bit vague, but the numbers back this up. The term “Yield” describes how the efficiency of manufacturing is measured; it’s the ultimate scorecard for a foundry. At 5nm, TSMC exceeds 90% usable dies per wafer. Samsung, TSMC’s largest and arguably only competitor, reaches 60%. The difference between the newer generation, the 2nm nodes, is even larger.

And when a single wafer costs up to $20,000, a 30% yield difference can decide whether a chip launch is generating or losing billions of dollars. Intel, for example, has been trying to regain its position as a leading-edge producer for quite some time now.

And it has been costly… Last year, Intel’s foundry division lost $13 billion on less than $18 billion in revenue. TSMC generated $41 billion in operating profit on $90 billion in revenue.

Add to that the trust Apple, Nvidia, AMD, and every other top customer put into TSMC and timely delivery. If TSMC can’t deliver, Apple’s shelves are empty, Nvidia and AMD can no longer supply Google, Meta, or Amazon with chips, and the high-tech world comes to a halt. Besides TSMC, no one can deliver that level of reliability due to their unpredictable yields.

But while AI companies rely on TSMC, TSMC itself relies heavily on one critical partner: ASML. ASML builds the EUV lithography machines mentioned earlier — marvels of engineering that enable the ultra-precise fabrication of advanced semiconductors.

The exact number of EUV scanners ASML produces isn’t public, but in 2023, industry rumors suggested the total output was just 55 units. In 2024 and 2025 combined, TSMC reportedly ordered 70 units on its own. That makes TSMC ASML’s single most important customer.

Both sides rely on and benefit from each other. ASML’s business is less cyclical since TSMC’s demand is the most stable in the industry, and in return, TSMC gets early access to ASML’s most advanced tools.

TSMC has also begun diversifying its manufacturing footprint by building new fabs outside Taiwan, with major projects underway in Arizona, Germany, and Japan. The largest of these is in the U.S., a $40 billion investment in Arizona that is expected to exceed $100 billion over time. These fabs are set to produce high-end nodes beginning in 2028.

At full capacity, the Arizona fabs are supposed to manufacture about 30% of TSMC’s most advanced generations of semiconductors. Currently, about 99% of those are made in Taiwan.

The facilities in Germany and Japan are smaller in scale and will focus on mature nodes for sectors like automotive, industrials, and consumer electronics.

However, replicating TSMC’s ecosystem outside Taiwan is nearly impossible. Surrounding TSMC’s fabs in Hsinchu and Tainan is a hyper-specialised supplier “city” that has taken decades to build. Local photoresist giants mix EUV chemicals inside the science parks, allowing TSMC to tweak a formula in the morning, and everything is ready by the end of the day for the night shift.

Ultra-high-purity gas lines from Air Liquide and others feed the tools in real time, and EUV mask blanks (crucial for the manufacturing process) can be polished just one highway exit away, so a $300,000 mask repair happens within 24 hours instead of a week-long trans-Pacific shipment. Of course, ASML is also on site, maintaining 24/7 field-service teams and spare-parts depots as needed, ensuring that even at 3am, any problem with one of the EUVs is fixed before the next shift.

Add to that a talent pipeline of 10,000 semiconductor graduates a year from Taiwan’s top Universities, such as NTU or NTHU. This entire ecosystem is why other companies cannot replicate what TSMC is doing. TSMC itself has problems replicating outside of Taiwan.

This naturally brings us to the risk aspect of TSMC’s story. It’s clear that the highest yields, and therefore the highest margins, are achieved in Taiwan. Building fabs abroad will almost certainly result in lower profitability and increased operational complexity. TSMC expects its gross margin to dilute by 2-3% per year due to the ramp-up of international fabs. However, in the long term, it still guides for gross margins of 53% or higher.

What might be even more important in the long run is the know-how and infrastructure that leave the country. There is even an argument to be made that by helping to build advanced infrastructure in places like the U.S., TSMC may inadvertently accelerate the rise of future competitors. This raises the question: Why diversify in the first place?

The Big Risk — China vs. Taiwan

For every superlative attached to TSMC: highest yields, widest moat, irreplaceable supplier, there’s one unavoidable reality: nearly all of its cutting-edge capacity sits about 100 miles from mainland China.

And Beijing has declared eventual reunification a national goal. In recent years, China held military drills close to Taiwan, violated their airspace, and ran cyberattacks. China also said it would consider military action to take control over Taiwan if no peaceful reunification can be achieved.

Any form of military conflict would inevitably shut down TSMC’s entire local production. And I’m fully aware that the production of semiconductors in such a scenario would be the least important thing.

Nevertheless, the economic, geopolitical, and technological consequences would be significant enough to make some experts argue that this very importance is what protects Taiwan.

This idea is known as the Silicon Shield. Any attack that destroys or idles TSMC’s fabs would cripple China’s own electronics industry as well as the West’s. TSMC’s CEO, C. C. Wei, has said that without TSMC’s engineers and supply chain, “the factory is a dead body.”

The logic of mutual dependency comforts some investors, including me, yet it does not eliminate tail risk; great-power politics can override economic rationality, as the Ukraine war reminds us. For China, this might be even more true.

Although a study of China’s history shows that it’s not a country of direct military conflict, that’s not how China operates. Henry Kissinger famously drew a comparison: while the West plays chess, a game of direct attack and defense, China plays Go, a game of gradual encirclement, where the objective is to dominate by patiently surrounding the opponent.

Valuation — Assessing Tail Risks

Valuing TSMC is a balancing act. On one side, you have one of the highest-quality businesses in the world, with dominant market share, structural growth tailwinds, and outstanding returns on both capital and incremental investment. By almost any metric, it’s a phenomenal business.

But on the other side lies a persistent geopolitical risk — one that, in a worst-case scenario, could lead to a complete capital loss. So, in my valuation model, I tried to capture both the strength of the business and the gravity of the tail risk.

Let’s start with the fundamentals. I structured the model around three core drivers of revenue: wafer volume growth, a shift in the mix to advanced nodes, and an increase in the average selling price (ASP) per node.

Given the industry’s cyclicality, I modeled an average annual growth rate of 10% through 2029 for wafer volume growth. After a dip in 2023, volumes recovered in 2024, growing 7.5%. This year and 2026 are expected to be much stronger, though. On average, 10% seems like a realistic estimate.

The second driver is the mix shift – each year, a larger portion of TSMC’s revenue comes from more advanced nodes like 3nm and, soon, 2nm. In 2024, the migration from 7nm to 3nm alone added roughly 12 % to wafer revenue, even without any pricing changes during the year.

However, for the model, I dial that back to a more sustainable 3% a year from mix alone. That might sound conservative, but it takes time to upgrade to new nodes again, so after a new generation, the shift will naturally slow down for a couple of years and draw down the average.

The third driver is pricing. Here, TSMC enjoys considerable pricing power. A 3nm wafer sells for over $20,000, while 5nm and 4nm nodes are typically priced between $16,000 and $18,000. Older nodes trade at far lower levels. So even though wafer volumes have yet to return to their 2022 peak, revenue per wafer has surged, which is one of the key reasons TSMC posted over 30 % revenue growth in 2024.

For 2025, TSMC has already announced price increases. Prices for 5nm and 4nm nodes are set to rise by up to 10 %, while 3nm prices are expected to climb around 4 %. In the model, I’ve assumed an average annual price increase of 4 % across all nodes, which feels reasonable given both past trends and customer dependence on TSMC’s capacity.

Putting it all together — 10 % wafer volume growth, a 3 % annual uplift from mix shift, and 4 % pricing tailwind — the result is total revenue growth of roughly 18 % per year. That’s slightly below TSMC’s own long-term guidance of 20 %, which historically has been a fairly reliable indicator.

Using an 8 % discount rate and an exit multiple of 24× earnings, which is above today’s level, but still a significant discount to peers and more than reasoanble for a company generating $40 billion in operating profit with 20% annual growth, I arrive at a fair present value of around $250 per share.

But today, we can’t stop at the base case. We need to address the tail risks — and specifically, how they affect the stock’s fair value. What I wanted to understand is how TSMC’s value changes when we factor in different probabilities of a total loss and let those risks compound over time.

Why take this approach? Because it reflects the true nature of the risk. This isn’t a one-off event, but rather an ongoing risk that investors face every single year. And just like in insurance or credit analysis, even small annual probabilities can compound into something far more material over time.

The table shows how different probabilities of a total loss affect TSMC’s fair value over a five-year holding period. While I obviously can’t tell you the “correct” probability of a geopolitical escalation, the math is straightforward: the higher the annual risk, and more importantly, the longer your holding period, the greater the cumulative impact, and the more it drags down TSMC’s present fair value.

The problem with TSMC is not related to its business. It lies in its terminal value. Perhaps that’s the reason why TSMC, despite world-class margins, 20% annual growth, and a near-monopoly position, only trades at 17x forward earnings, while Texas Instruments trades at over 30x.

The most relevant comparison would be Samsung’s foundry division, but because it’s part of the broader conglomerate, we can’t isolate clean financials for just the foundry business. Even Intel, which continues to lose ground in both technology and execution, trades at a higher multiple, despite being a fundamentally weaker business.

Portfolio Decision

Shawn and I didn’t take this decision lightly. If you’ve listened to the podcast, you’ll know we actually postponed the investment to first speak with members of our community. With backgrounds spanning aerospace, software engineering, semiconductors, and AI, we saw an opportunity to dig deeper into the technological edge that makes TSMC so dominant — why no other company can match its yield, scale, or execution, and what makes its lead in advanced nodes so durable.

Those conversations were incredibly helpful, but they also brought us right back to the geopolitical risk and what the math behind compounded probabilities really means for a long-term investor. Coming out of those discussions, two things became clear:

First, TSMC’s moat is just as wide as advertised. While the semiconductor industry is known for its rapid cycles and constant disruption, TSMC has built a position of strength that no other company in the sector has ever achieved.

Second, and just as important, was the realization that this tail risk likely never goes away. And with each passing year, it compounds. Combine that with the persistent discount the market applies to TSMC, and you’re left wondering whether the valuation will ever truly reflect the quality of the business.

In the end, we placed TSMC on the too-hard pile. It might well become one of the best compounders of the next decade, but it also carries a risk of going to zero. For an investing approach that emphasizes margin of safety, that’s a tough position to justify, especially at current prices, which are near all-time highs. There’s clearly a discount to peers, but not to TSMC’s own historical valuation.

For now, we’re holding off. There may come a time when the market prices in more fear, and TSMC trades at a level that offers a more compelling risk-reward profile. Until then, we’ll keep watching closely.

Weekly Update: The Intrinsic Value Portfolio

Notes

Adobe reported earnings on Thursday, and the results were very good. Not only did Adobe beat revenue and earnings estimates, but it also guided for double-digit revenue growth in the years ahead, about 10%, and a further margin expansion from already best-in-class. 45%. Still, Adobe stock sold off 5% in response to the earnings release.

It’s more than apparent that the market is not buying Adobe’s guidance and continues to believe that it will be hurt by the developments in AI. We have argued before that we believe Adobe is actually a beneficiary.

If you want to read about that, here’s our Newsletter on Adobe.

Quote of the Day

"Rule No.1 is never lose money. Rule No.2 is never forget rule No.1.”

— Warren Buffett

What Else We’re Into

📺 WATCH: Henry Kissinger: On China at Charlie Rose

🎧 LISTEN: Mastering the Capital Cycle w/ Clay Finck

📖 READ: A Whitepaper by NZS on Semiconductor’s

You can also read our archive of past Intrinsic Value breakdowns, in case you’ve missed any, here — we’ve covered companies ranging from Alphabet to Airbnb, AutoZone, Nintendo, John Deere, Coupang, and more!

Your Thoughts

Do you agree with the portfolio decision for TSMC?Leave a comment to share your thoughts! |

See you next time!

Enjoy reading this newsletter? Forward it to a friend.

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here.

Use the promo code STOCKS15 at checkout for 15% off our popular course “How To Get Started With Stocks.”

Follow us on Twitter.

Read our full archive of Intrinsic Value Breakdowns here

Keep an eye on your inbox for our newsletters on Sundays. If you have any feedback for us, simply respond to this email or message [email protected].

What did you think of today's newsletter? |

All the best,

© The Investor's Podcast Network content is for educational purposes only. The calculators, videos, recommendations, and general investment ideas are not to be actioned with real money. Contact a professional and certified financial advisor before making any financial decisions. No one at The Investor's Podcast Network are professional money managers or financial advisors. The Investor’s Podcast Network and parent companies that own The Investor’s Podcast Network are not responsible for financial decisions made from using the materials provided in this email or on the website.