- The Intrinsic Value Newsletter

- Posts

- 🎙️ Uber: Cash Burner to Compounder?

🎙️ Uber: Cash Burner to Compounder?

[Just 5 minutes to read]

Uber needs no introduction. We’ve all used it, we all probably have our gripes with it, and yet, it has fundamentally changed the modern world. A few weeks ago, in our newsletter on Airbnb, I joked that Uber convinced the world to ride in strangers’ cars, and Airbnb convinced them to sleep in strangers’ homes.

This gave rise to a 2010s movement known as the Sharing Economy, which has now become so ingrained into modern life that it’s more accurate to just call it “the economy.”

I’ll be the first to say I never thought much about Uber as an investment. Driver and car insurance costs impose strict limits on economies of scale, meaning that the business doesn’t benefit from the same operating profitability at scale as a company like Microsoft, where there really aren’t any additional costs to selling one more software subscription to Microsoft Office.

Yet, they’ve made the economics work. Now, new fears stem from the idea of autonomous vehicles displacing Uber. I was actually one such investor who, when researching Alphabet previously, suggested Waymo could and should eventually cut Uber out instead of partnering with them.

After having studied Uber, I now see it differently. Let’s discuss 👇

— Shawn

Profit From Your Passion: Invest In Bourbon Barrels — Together With CaskX

CaskX makes it possible to invest in full barrels of bourbon from top Kentucky distilleries. As bourbon ages, so does its value—making it one of the few investments that actually improves over time.

With global demand on the rise and limited supply, now’s the time to diversify beyond stocks and traditional investments. For Intrinsic Value Newsletter readers, we’re offering early access to our latest portfolio featuring barrels from award-winning distilleries that are shaking up the industry.

Uber: Ride-Hailing Economics — Winner Take Most?

No Longer A Cash Burner

On the podcast this week, I (Shawn) pitched Daniel on Uber, and if you haven’t listened yet, well, ya should — we had a ton of fun together and dove much deeper than is possible in a newsletter format.

What I love about researching companies like Uber is they really challenge my preconceived notions. I came into Uber heavily biased by what I’ve read about them over the years: I knew they burned cash, had long been unprofitable, had a bad reputation for taking advantage of drivers, and couldn’t benefit from the same economies of scale as other tech giants since its business is so rooted in the physical world.

On that last point, for Uber to increase revenues, they need to either deliver more Uber Eats food/grocery orders or they need to transport more people from point A to point B, and both of those things require more drivers.

In other words, they can’t really grow the business without correspondingly scaling variable costs related to driver pay and the vehicle insurance they provide to drivers, so they’re destined to be more like Amazon or Walmart, which operate at a massive scale but have very slim profit margins.

Now, those aren’t bad businesses to be like, but unless you’re truly an incredible operator that has mastered capital allocation (as Walmart and Amazon have), as an investor, I’d typically prefer companies with a little more room for error through structurally higher profit margins (think Alphabet and Airbnb.)

And then, when you factor in the seemingly inevitable adoption of autonomous vehicles that will disrupt Uber’s business, I just didn’t see anything to love, nor did I think the $150 billion+ valuation it sports made any sense.

Well, after digging in, I see things differently.

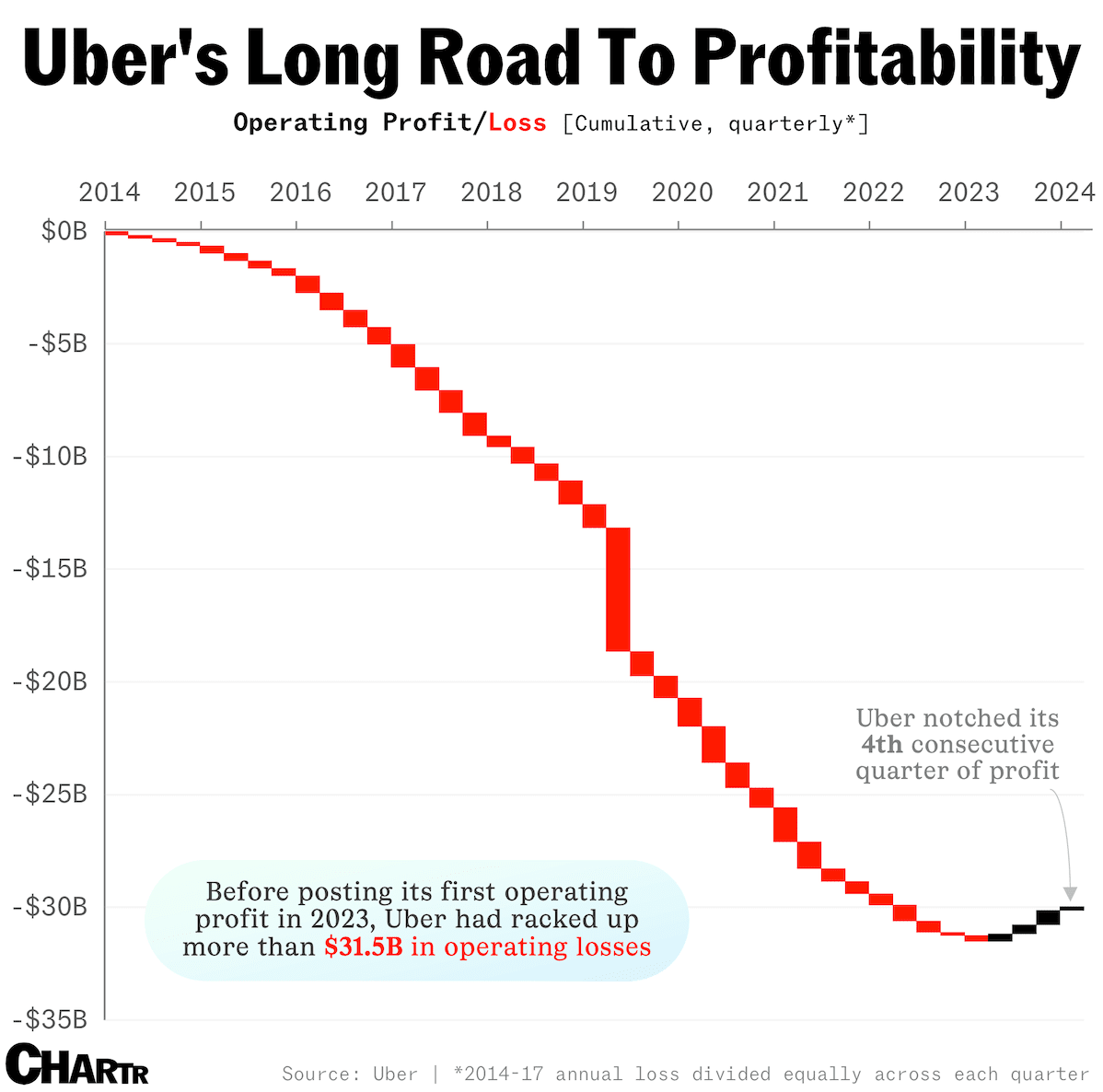

For starters, as of 2023, Uber is finally profitable:

Yikes!

Inflecting To Profitability

The days of accumulated losses are behind Uber. In fact, years of unprofitability can now be “carried forward“ in tax accounting parlance to reduce the company’s tax payments in the future, but that’s another story.

My focus is on the reality that Uber has finally reached enough scale to not only unlock marginal profitability but transform into a much more promising business.

For example, now that Uber is the clear leader in many major markets, it doesn’t have to excessively undermine itself and its competition with promotions and discounts, allowing it to charge more normalized rates and earn larger fees (on both Uber rides and Uber Eats deliveries).

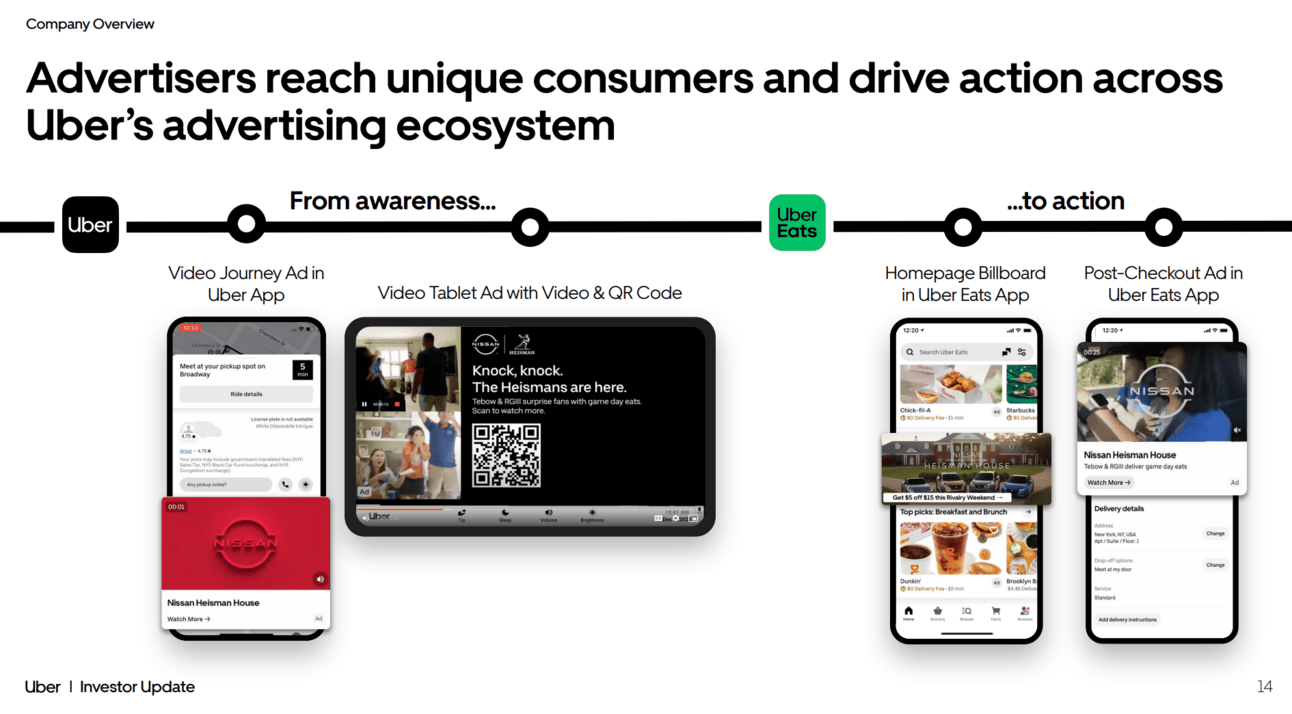

Also, as part of its scale, Uber has attracted enough advertisers to now wield a billion-dollar-plus ads business that will only keep growing.

Uber’s management is targeting ad revenues at 2% of “gross bookings,” suggesting the ads business could 5x within the next five years — providing a major tailwind for top-line growth as well as margins since advertising doesn’t come with the same costs as, say, driving someone to the airport.

For Uber, advertising comes in two primary forms:

Ads in Cars: Uber drivers can strap devices to the backs of seats and show ads to passengers to earn extra revenue. This is more powerful than you might think, given A) that tens of millions of people frequently ride in Ubers and B) Uber knows exactly where they’re going, which is very valuable to advertisers.

In-vehicle ads

If you’re coming home from the airport after a long trip, I bet some local spa and massage businesses would love to show you an ad while sitting in your Uber.

Or maybe you’re Ubering to work, and a local restaurant wants to plant a seed in your mind for what you’ll order for lunch. It doesn’t take much creativity to see how valuable this can be(!)

Uber drivers can also put ad signs on top of cars that act like just general billboard ads

Ads In-App: Uber has tried running ads for local businesses in the Uber app, which has been less popular than hoped, but more compellingly, the company has found considerable success with sponsorships in its Uber Eats app

In-app ads

Sponsored searches have been very popular. Searches like “Burgers food near me” may come with a sponsored result from Wendy’s at the top, or when you first open the app, the suggestions made to you may be sponsored.

This actually strengthens Uber’s network effect further because not only do local restaurants need to be on the Uber Eats app to compete, but they may even need to run ads to counteract ads being run by competitors. For example, if there are two Italian restaurants in town, and one starts aggressively running ads on Uber Eats, the other will probably be compelled to respond with their own ads(!)

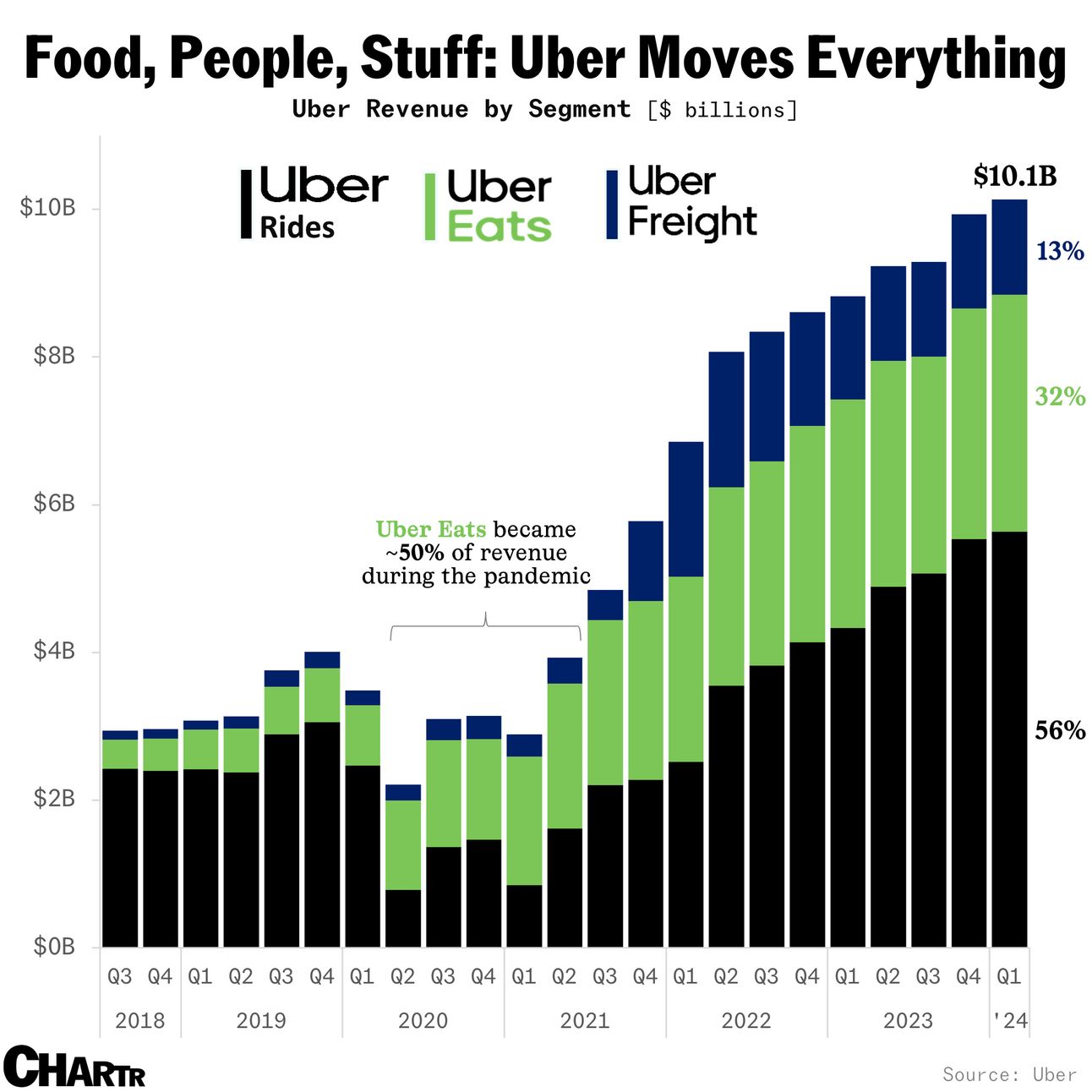

What Uber Does

To take a step back, let’s all get on the same page about what Uber does. There’s Uber Rides, which the company refers to as its “Mobility” unit, and then there’s Uber Eats, which the company refers to as its “Delivery” division.

Both are premised on moving things from one place to another, whether that be transporting people home from the bar or to the airport, or delivering Chick-fil-A to your doorstep (yum.)

You might not know, though, about Uber’s third and much smaller, unprofitable division known as Uber Freight.

Uber Freight is Uber for commercial shipping, connecting truck drivers with freight shippers who need to move inventory from place to place.

See the handy graphic below for context:

On top of this, Uber has very substantial cross-holdings on its balance sheet that are relevant to its intrinsic value. This has come about because, even though Uber is global, it couldn’t spread to every market before local competitors had the idea to use the Uber Playbook against them.

For a variety of competitive and political reasons, Uber has pulled out of places like China, Southeast Asia, and Russia, because it simply would’ve been a race to the bottom to remain, and they weren’t the first mover.

Rather than just calling it quits entirely, though, they would sell their operations off and take stakes in the competitor set to win a given market, thus explaining how they racked up $8.5 billion worth of stakes in companies like Didi (the Uber of China), and Grab (the Uber of Southeast Asia), among others.

I actually really like these pragmatic decisions. Not to say this doesn’t come without opportunity costs, but being able to recognize where you can’t win and still positioning yourself to benefit from sizable stakes in those who beat you in a certain region strikes me as being very effective, especially since these competitors are relatively contained to their geographic niches.

This is vastly more preferable than sinking billions into competing in markets where it was otherwise clear that Uber was operating at a disadvantage.

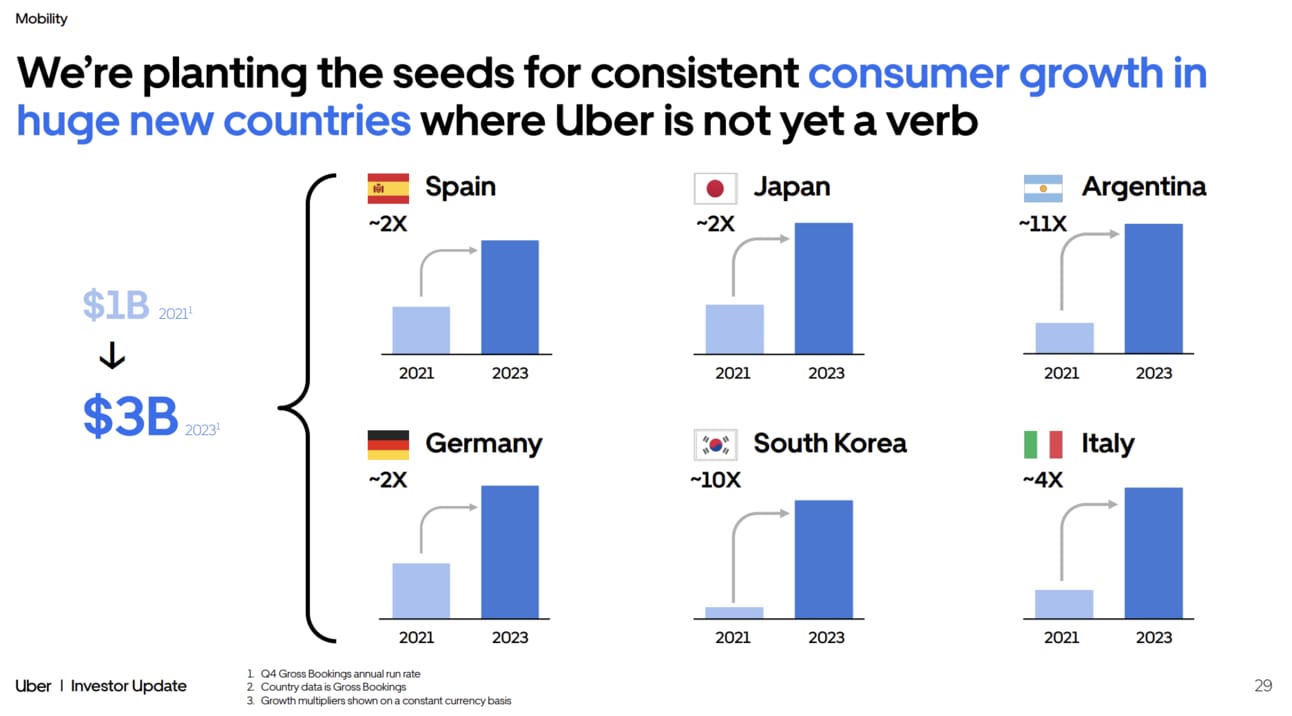

That is not to say Uber is established in some markets and abandoning growth everywhere else. On the contrary, in places like Spain, Italy, Japan, Argentina, and South Korea, adoption is scaling quickly (though competition is more intense in some places than others).

See the following from Uber’s investor update presentation:

Uber, Autonomous Vehicles, and Bill Ackman

Alright, let’s move on to the part of the newsletter everyone has been waiting for: Our discussion of Bill Ackman.

I’m kidding, of course. Bill Ackman did, however, recently come out in praise of Uber, arguing that the company is hugely undervalued after taking a $2 billion+ stake in it.

Ackman has, well, something of a mixed reputation these days after making political forays and seeming to spend a lot of time on Twitter/X (maybe a little too much?)

Nonetheless, when Ackman moves, millions follow, and after he announced his position, the stock leapt 7%. This isn’t consequential to my thesis by any means; I don’t aim to follow Ackman into any stock, nor any investor for that matter.

What I want to focus on, and this is something that Ackman is apparently in agreement with Uber’s management on, which is that the autonomous vehicle revolution offers a massive opportunity for Uber, much more opportunity than risk.

Uber’s CEO (and Ackman) have referred to autonomous vehicles, aka AVs, as a $1 trillion+ opportunity. That’s, uhh, pretty big!

From Uber’s official filings

I quite literally have no idea how they determined that, and I’m going to go out on a limb and say that this is maybe, just maybe, a little optimistic.

But the real point is that rather than AV taxis obsoleting Uber, making it the next big example of economic relics from history like VHS tapes, Blockbuster stores, Walkman music players, Blackberry phones, and pagers, there’s a plausible scenario where Uber isn’t brought to its knees by AV adoptions and actually comes out stronger for it (while the market has started to price Uber as if these AV disruptions are imminent.)

For starters, not having to pay drivers would be a massive cost savings, boosting margins. That is, of course, all for nothing if people aren’t ordering Uber anymore because Waymos has taken over every major city and become the preferred way to hail a ride.

Here’s why that undesirable scenario (for Uber) may not come to fruition:

Firstly, Uber and Waymo are partnered, and they’re likely to remain partnered together because Uber has developed the most sophisticated ridesharing platform technology in the world and has the widest network effects surrounding its business — things that Alphabet (Waymo’s parent company) can’t easily recreate.

More importantly, but relatedly: Going into the AV business doesn’t mean going into the ridesharing business. This should be obvious, but bears repeating. Waymo is in the business of turning vehicles, historically driven by humans, into vehicles that are self-driving, which is a very different business model than trying to build a ridesharing platform.

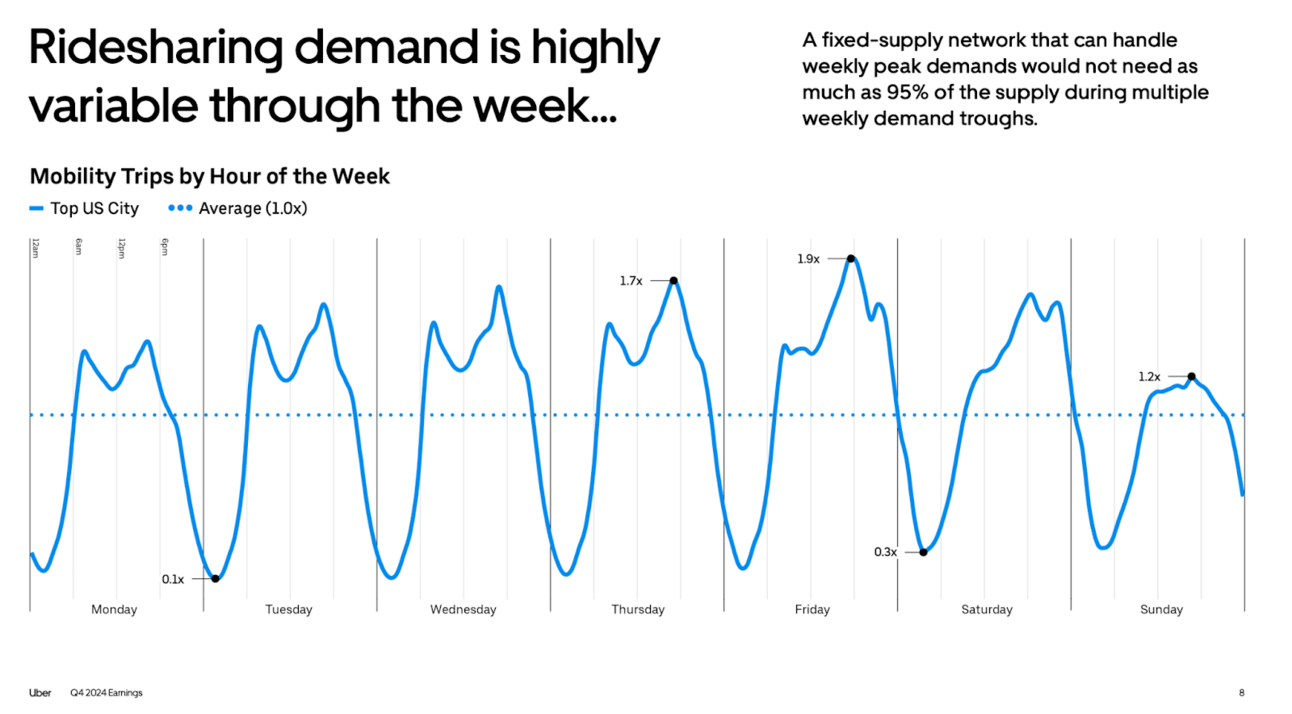

For example, ridesharing demand is highly variable throughout the week and throughout the day, so AV fleets couldn’t efficiently dislodge Uber with their own ridesharing platform, as they can’t naturally match demand and supply.

How come? At any given moment, such an AV competitor, since they would directly own the vehicles and allocate them across different cities globally, would either have too many AVs or too few in any given place, either making the platform unreliable (not enough AVs to provide rides at all times of day) or too expensive to run (an almost constant surplus of cars to absorb surges in demand.)

The beauty of Uber’s model is that its platform naturally responds to surges in demand. Uber drivers are part-time contractors, and as such, if there’s a surge in booking requests at 6 pm on a Friday, they can jump in their car and start completing rides, and once requests fall off, they can just go offline and return to their regular days.

They help absorb requests as needed and earn compensation as they fulfill rides, but they aren’t paid a minimum wage or otherwise cost anything to Uber once they’re offline — contrast that with maintaining a fleet of AVs that, most of the time, would be unused, or at best, underutilized.

Again, such adaptability and flexibility aren’t even remotely possible with a fleet of AVs hoping to displace Uber’s ridesharing platform, which is why companies like Waymo have found it far more attractive to partner with Uber rather than try to displace Uber.

From Uber’s presentation to investors

Waymo AVs are actually a great way to add more supply onto Uber’s network without trying to completely replace it, and I suspect this dynamic will hold well into the foreseeable future, strengthening Uber’s network effects and profitability (management has said Waymo-Uber rides are so popular they can charge a premium for them, despite them being operationally cheaper than regular rides since there are no drivers.)

Okay, you might still wonder what would happen to Uber if AVs do prove to be adversely disruptive?

I’d argue this is a very distant concern. As mentioned, for the time being, companies like Waymo are choosing to partner with Uber instead of competing.

Additionally, while certain cities may have very high AV adoption rates that disrupt Uber, this will not happen globally all at the same time — it’s going to be a very long time before India has the same rates of AV ownership as San Francisco! And you could probably even say the same for Paris, London, and other cities across the U.S.

Adoption will be slower than most people anticipate and may not even reach some countries, in terms of consequential rates of adoption, for many decades.

And if that wasn’t enough to assuage your concerns, I should add that half of Uber’s business is food delivery through Uber Eats, which, unless we have armies of robots and drones picking up and delivering our food (maybe one day!), doesn’t exactly stand to be disrupted by AVs anytime soon.

So, between some cushioning from Uber Eats, and slower adoption of AVs worldwide and across parts of the U.S. — assuming AVs even are a negative for Uber’s business and not an opportunity as management thinks, I just don’t see this as something worth losing sleep over. At least, not for the next 5 years.

What This Means For Investors

Alright, so what does this all mean for investors? Well, to me, it means that Uber is very reasonably valued, given that revenues from its core business are expected to grow between 15-20% per year over the next few years, while earnings per share grow at more than 30%, thanks to improving margins and aggressive share repurchases.

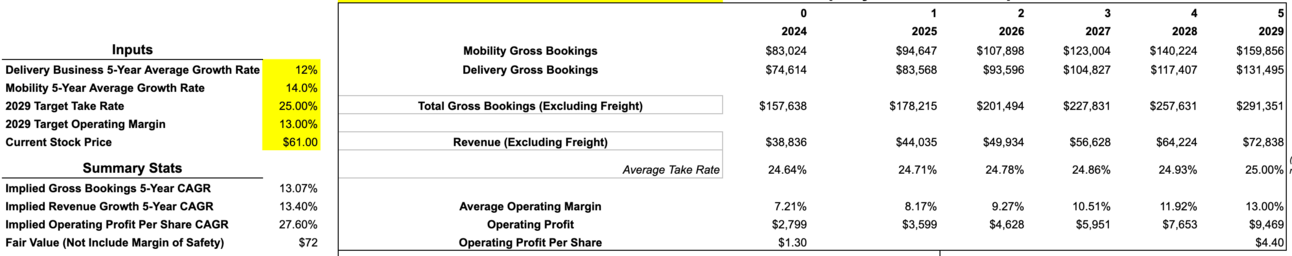

From Bill Ackman’s presentation on Uber

That brings us to another elephant in the room: stock-based compensation. For anyone who read our research on Reddit and Airbnb, you’ll know this is a familiar issue for tech companies.

All I’ll say is that, like these other two companies, Uber seems to be beyond the stage of significant dilution and now, thanks to its massive upswing in profitability in the last two years, can comfortably afford to more than offset the dilutive effects of the stock-based compensation it uses to retain employee talent.

Going back to the growth story for Uber, I don’t have time to cover every single thing they’re doing and can do, but trust me when I say it’s a lot.

From more obvious things like expanding internationally, growing adoption further in its core markets, and providing membership bundles for its most loyal users (like Uber One, which offers 6% credits on Uber rides, free Uber Eats deliveries, and other discounts), to programs like Uber Health, where the elderly or those who live alone or anyone else can use a specialized transportation service to bring them to and from non-urgent appointments, to Uber Teens, which allows teens to book their own Uber rides home from, say, basketball practice while parents can track their location at all times.

There’s also Uber Black for business travelers looking for first-class experiences, Uber Courier for sending packages back and forth, or simply Uber’s willingness to partner with Taxi groups in Japan to bring over 20,000 taxis onto the platform.

I’ve been blown away by all the different ways they’ve reimagined how Uber could create value, and I can confidently say I’m not doing these initiatives proper justice, either.

There’s also so much room to do more with advertising, as we touched on a bit earlier, and yet, when you adjust Uber’s free cash flow for stock-based compensation expenses, the company is only valued at about 30x FCF — very reasonable for a company of Uber’s quality and growth prospects.

The underlying business is growing as fast as ever in recent memory and is more profitable than ever (and increasingly so), and that is to say nothing of how share repurchases may reduce the share count going forward (increasing shareholders' ownership slice in the company).

There’s too much to cover here, but I go into more detail in the podcast with Daniel on competitors, AVs, and growth plans through cross-promotion — see the below graphic for reference, so make sure to give that a listen, but let’s look more at the valuation.

Uber is successfully converting Uber Eats customers to riders, and riders to Uber Eats customers

Valuing Uber

I’m not doing any rocket science here. There are people who have done much more extensive modeling than I have. My goal with valuation is to simply ground my qualitative understanding of the company and its prospects with numbers that allow me to very roughly imagine what the company is worth in different scenarios.

As my “base case,” I went with management’s guidance that they can grow revenues by 15-20% over the next two years or so, with that tapering off to average about 10% per year by 2029.

Then, thanks to advertising mostly, I accounted for Uber’s take rate slightly growing (the percentage of gross bookings that they capture as revenue), and then I assume some continued economies of scale that boost operating margins to 15% by 2029 (analysts expect operating margins to reach 12% next year, up from 6% in 2024.)

I don’t make any bold assumptions about stock-based compensation, and I just, probably lazily, assume that the share count will be roughly flat as repurchases offset grants to employees.

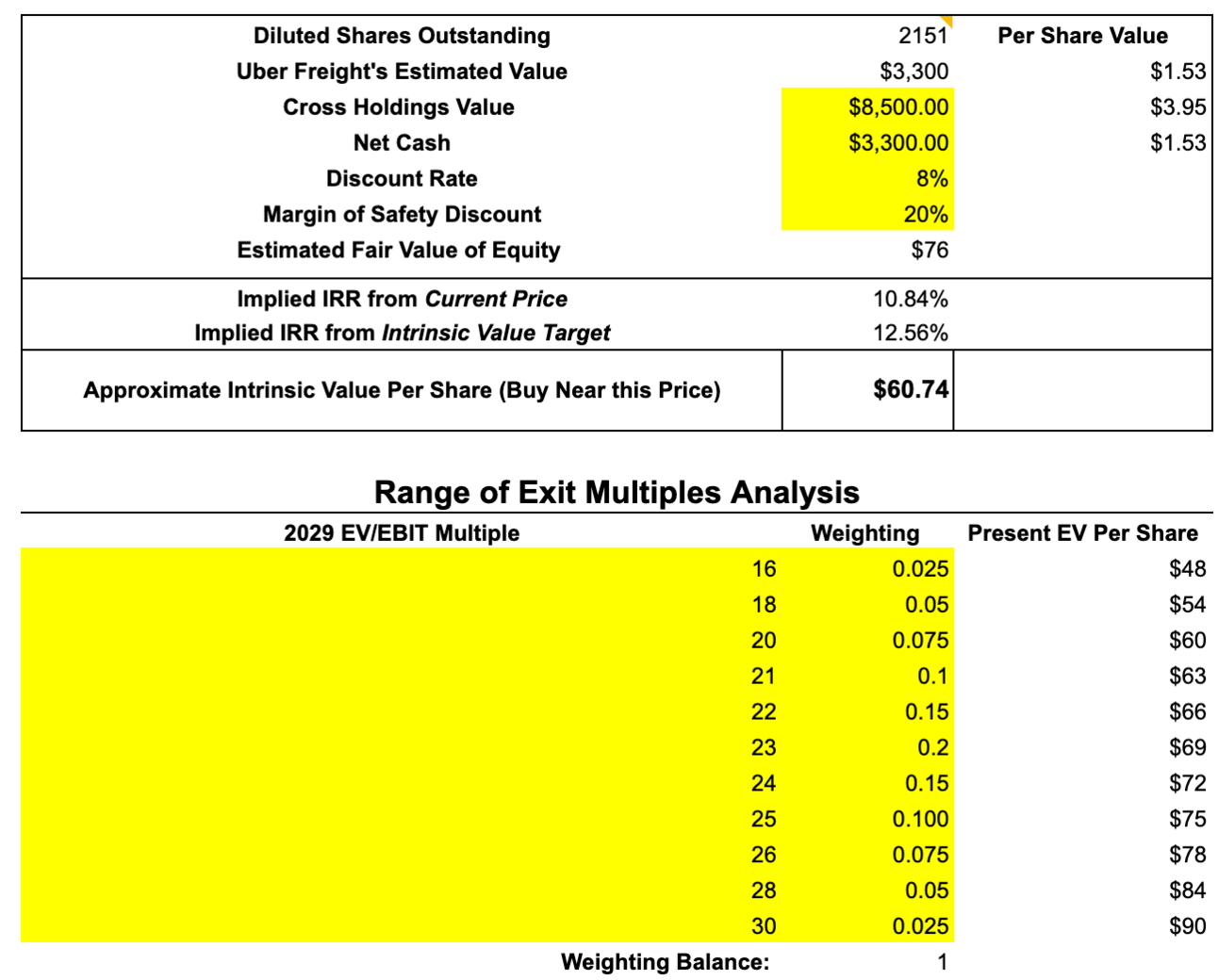

So, with that, I have an idea of what Uber’s operating profits per share will look like by 2029, and from there, I can try to value the entire enterprise by using a range of plausible exit multiples at that point in time. For context, Uber currently trades at 55x operating profits (EV/EBIT), which will almost certainly come down as the business matures further.

And the question is, how far will this come down? Will it be like Amazon today (mid-30s EV/EBIT valuation), Airbnb (high-20s EV/EBIT), or Alphabet (high-teens EV/EBIT.)

There’s a lot that goes into a company’s multiple, and I prefer the unscientific approach of using peer comps to help set my floor and ceiling for a plausible range of multiples and then simply calculate a weighted value, with the middle of the range having the most weighting. Again, I’m the first to admit it’s not a fool-proof approach, but we are ballparking here, folks.

With all that said, we also must discount that 2029 value to present dollars, add in a margin of safety (in this case, I went with 20%, reflecting the uncertainty around the company’s future), and, importantly, we can’t forget to account for Uber’s $8.5 billion worth of equity in companies like DiDi and Grab or its net cash (Uber has more cash than debt.)

What we’re doing here is converting Uber’s enterprise value into a per-share equity value. If we had used, say, P/E or P/FCF instead of EV/EBIT, then we wouldn’t have to add back net cash and cross-holdings, but I feel more confident modeling out operating profits than earnings/free cash flow for this company.

You also might notice that I didn’t explicitly account for Uber Freight in my model, which is focused on the Mobility and Delivery businesses. For simplicity, I opted to treat Uber Freight like one of these cross-holdings and not account for it until the end, when I added back its value at around $3.3 billion, which is the valuation the unit received when it was considering an IPO back in 2023.

Finally, we get to an intrinsic value target of a little over $60 per share, where we’d expect a 12.5%+ annual return if we can get Uber around that price:

Click below to download for yourself

You can view the file for yourself here (feel free to click “File” and “Download” to add in your own assumptions.)

Let me say that, after all the uncertainty that has gripped the markets recently around tariffs and recession fears, I decided to review my weightings and range of exit multiples to be somewhat more conservative, so my intrinsic value target that I share here is a bit lower than the target I share in the podcast (about $74 per share.)

Portfolio Decision

Given that Uber has been trading around this updated intrinsic value target of late and, more importantly, because of my feeling that the market is too pessimistic about Uber’s prospects with respect to AVs and the very promising ways they can grow their business, I made the case to Daniel that we add it to the portfolio.

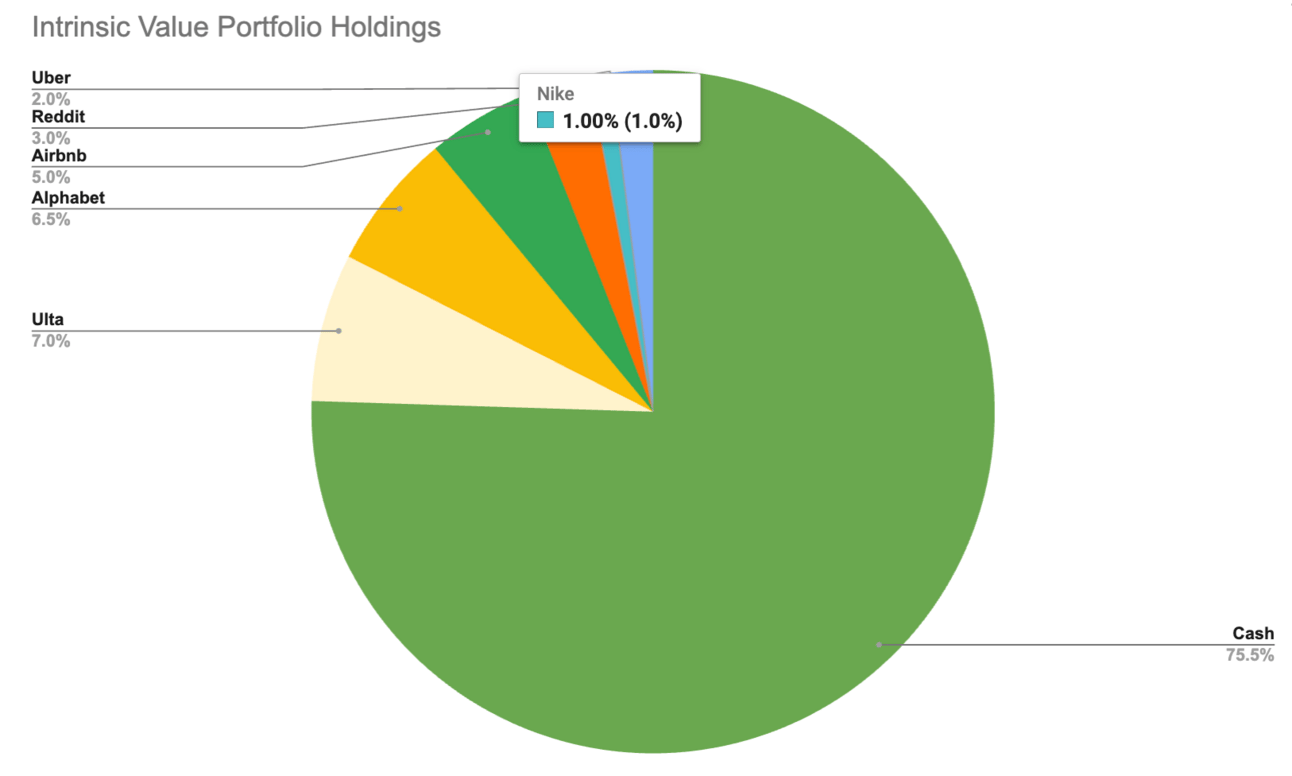

We agreed to make it a relatively small position for now as a 2-3% holding, but this could certainly increase over time if we get even more attractive prices and as we eventually begin to rebalance the portfolio.

More on the portfolio decision in our weekly portfolio update below.

Weekly Update: The Intrinsic Value Portfolio

Notes

For the sake of full transparency, I did my research on Uber well over a month ago, and Daniel and I recorded our episode together before the tariff-induced market metldown of early April, so I used that panic as a chance to add Uber to my personal portfolio and to our Intrinsic Value Portfolio at about $62.31 per share. Daniel and I had already agreed to try and add it at that point, and I wasn’t expecting Uber to so suddenly and briefly bounce toward our buy price target — I couldn’t help myself but capitalize on that opportunity before this newsletter was even published.

So, I added Uber as just a 2% position, and if we retest those tariff lows in Uber’s price (around $60 per share), or go lower, I’ll recommend to Daniel that we grow our stake in Uber to 3%. We will just have to wait and see if we get that chance.

What Readers Said About Last Week’s Newsletter

Readers, at least based on those who answered our poll, disagreed with the conclusion to initiate a small position in Nike’s beaten-down stock. Here’s what others were saying about Nike:

“Too much competition. It's lost its mojo. Tariffs will take a big bite on profits, or they will have to cap-ex new factories and bots to make it work.”

“I think that, although Nike is certainly a solid company now back to a proven leadership, its share price is still too high, not yet offering that margin of safety I would hope for. At least below 50 would be a start, also given the fair value you shared in your very appreciated newsletter issue.”

“Consumer trends are fading against Nike. Look around at gyms and on walks. They won’t demand a premium multiple based on historical standards.”

“It’s tired. The logo is easy to copy for cheap knockoffs. The status symbol is no longer respected as much with the young. The product is no longer, ‘THE Product.’ The strategy is too obvious and lacks distinctive variation. Success over the years has killed the brand. It is not new, original, or distinctive. Compare it with Crocs.”

“Great post, but NKE today ain't the NKE of yesteryear. Until they can figure out how to innovate and become the AAPL of apparel and shoes, they're not going to be long-term investable.”

“$NKE is a great pick, I've been wanting to buy this company for over 10 years. Finding great companies at a discount is always uncertain because there must be unknown fear in the market to get it to that price.”

Quote of the Day

"You never really know a stock until you own it.”

— Walter Schloss

What Else We’re Into

📺 WATCH: Costco’s CEO breaks down how a Kirkland product gets made

🎧 LISTEN: The Dhando Investing Playbook with Kyle Grieve

📖 READ: A historical analysis of tariffs

Your Thoughts

Do you agree with the portfolio decision for Uber?(Leave a comment to elaborate!) |

See you next time!

Enjoy reading this newsletter? Forward it to a friend.

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here.

Use the promo code STOCKS15 at checkout for 15% off our popular course “How To Get Started With Stocks.”

Follow us on Twitter.

Keep an eye on your inbox for our newsletters on Sundays. If you have any feedback for us, simply respond to this email or message [email protected].

What did you think of today's newsletter? |

All the best,

© The Investor's Podcast Network content is for educational purposes only. The calculators, videos, recommendations, and general investment ideas are not to be actioned with real money. Contact a professional and certified financial advisor before making any financial decisions. No one at The Investor's Podcast Network are professional money managers or financial advisors. The Investor’s Podcast Network and parent companies that own The Investor’s Podcast Network are not responsible for financial decisions made from using the materials provided in this email or on the website.