- The Intrinsic Value Newsletter

- Posts

- 🎙️ Hermès: How much is the Best Brand in the World worth?

🎙️ Hermès: How much is the Best Brand in the World worth?

[Just 5 minutes to read]

Retail companies are a tough place for investors. Brands come and go, and what looked like a phenomenal business two years ago might be a dumpster fire today.

You can say something similar about automotive brands. There’s less churn among the top names, sure—but the cyclicality still makes the sector pretty unattractive.

We would know. We’ve looked at automotive companies before, and we’ve looked at plenty of retail names. But in both sectors, there’s a subcategory that stands out: luxury companies.

Ferrari isn’t like other car companies. One look at the financials and you have no doubt about that. And LVMH isn’t your typical retailer. Yet there’s one luxury fashion house that stands above all others: Hermès.

Yes, Hermès trades at a premium. But historically, that premium hasn’t stopped shareholders from outperforming the market. Over the last decade, Hermès traded at an average P/E of roughly 48x and still delivered annualized returns north of 20%.

The goal of today’s newsletter is to figure out whether the next decade can look anything like the last one.

Let’s dive in!

— Daniel

Last Chance: Join The Intrinsic Value Community

Over the last few weeks, we’ve shared that applications are open for a new cohort of The Intrinsic Value Community, and this will be the final announcement for this intake.

At this point, there are fewer than a handful of spots left. If joining has been on your mind, now is the time to submit an application. Once the remaining seats are filled, the cohort will close.

A big thank you to everyone who has already applied — it’s been genuinely fun speaking with you 1:1 and getting a sense of what you’re building as an investor.

If you want to be part of this cohort, head to the link below to learn more and apply. Once it closes, that’s it for this round.

Hermès – Made for Eternity

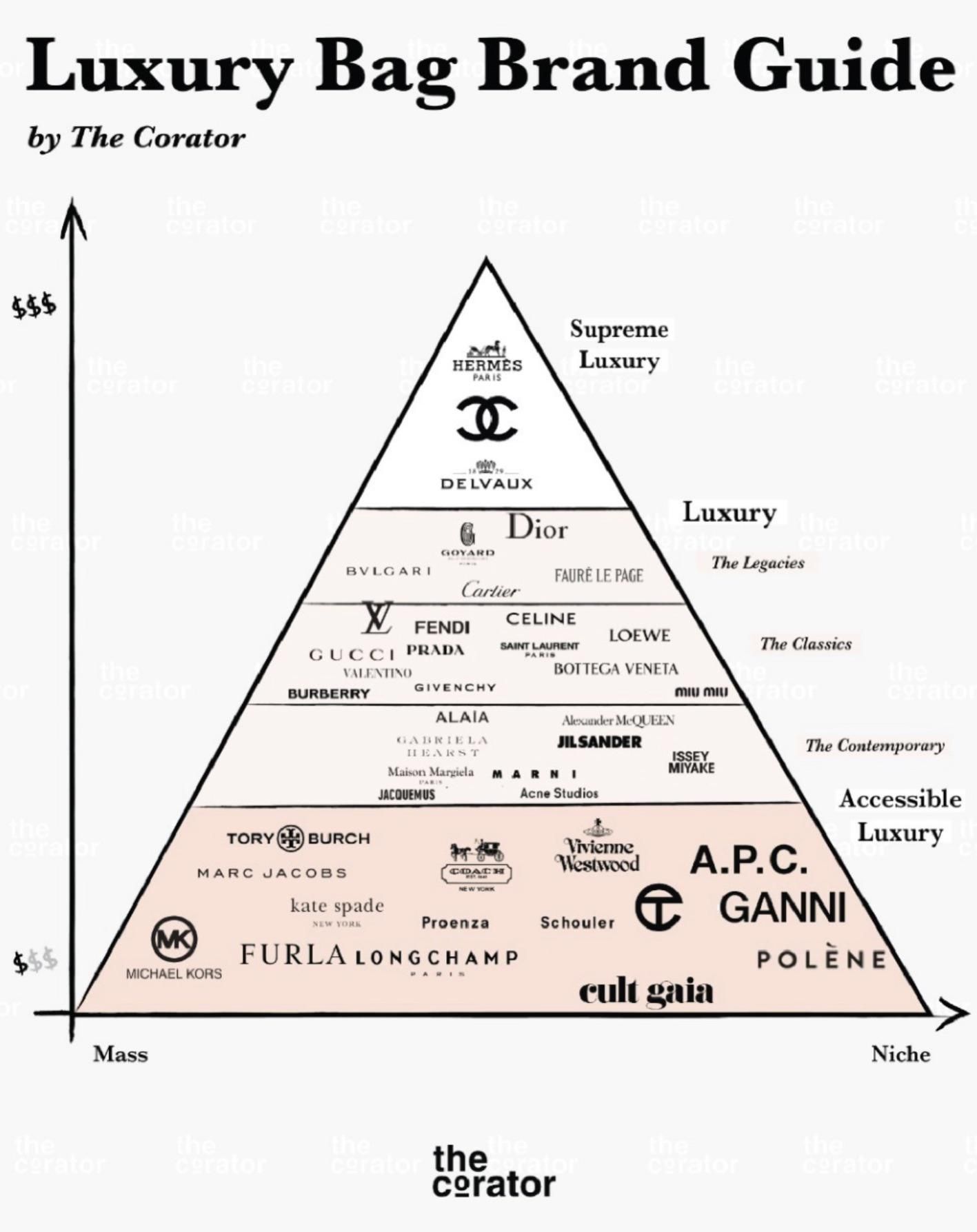

There are three perspectives you can take to show just how different Hermès is from other luxury brands. In luxury investing circles, there’s a hierarchy usually portrayed by a pyramid.

No matter which one you look at, Hermès will be on top of that pyramid on all of them. It’s the ultimate level of luxury. One that, to some extent, can’t even be bought with money. At least, there’s no guarantee.

But we don’t even have to rely on fashion experts and their opinions. As finance guys, we trust the market. Okay, that sounds a bit cliché. But honestly, there are way more fashion-versed people than Shawn and me. And still, if you look at the market and the consumer, you can’t miss that Hermès is viewed differently.

Just compare Hermès’ stock chart with other luxury names like LVMH, Kering, or Burberry. You’ll see that all of them are meaningfully more volatile than Hermès. Luxury brands love to market themselves as “anti-cyclical,” but only a few can actually deliver on that promise. And Hermès is one of the few.

An even easier way is to look at the multiples the market is willing to pay for a dollar of earnings. If you compare LVMH to Hermès, you can clearly see that the market consistently gives Hermès a hefty premium.

Last but not least, ask yourself how many LVMH bags you see when you walk outside and compare that to how many Hermès bags you spot. Sure, Hermès is harder to clock because it doesn’t rely on such a noticeable signature print. But I’d bet a good chunk of my portfolio that you see at least ten times more LVMH bags when you walk through your city.

Normally, you want your product to be everywhere. But as we all know, luxury often breaks many “normal” business rules. Luxury is scarcity, exclusivity, and that little dopamine hit of feeling special. If you’re carrying a Birkin, Hermès’ most iconic and exclusive bag, it loses a lot of its mystique if you bump into a dozen other people with the exact same one on your way to get coffee.

That’s also why counterfeits are such a risk for luxury brands. In small doses, they can even feed the aspirational image – people see the logo everywhere and start wanting the real thing. But once there are too many fakes, the dynamic changes. At first glance, it's hard to tell whether it’s real or fake, and constant exposure to the print can make the brand feel “cheap” to the very customer base that’s supposed to value it most.

When I see someone wearing a Gucci cap or bag, my default assumption is that it is fake. You don’t ever want that to happen as a brand.

The Gaiting Mechanism

If you listened to our Hermès episode, you’ll have heard Shawn and me spend a good 15 minutes, maybe longer, talking about the so-called “Gating Mechanism.” It’s a pretty common practice among the most exclusive luxury brands in the world, regardless of the category. Ferrari, Patek Philippe, Hermès… they all do it.

In practice, it means they won’t sell you their most in-demand products even if you have the money. Those pieces are reserved for loyal customers with a long track record. You could be a Hollywood actor, and yet, if you’re not a regular Hermès client, you still won’t get the chance to buy a Birkin.

So when you see someone carrying a Birkin, you can be pretty sure they didn’t just pay the ~$30,000 sticker price. They’ve likely spent multiples of that on other Hermès products just to earn the right to buy one.

It’s a relationship-based system that works a bit like a leveling system. When you first walk into an Hermès store, you’ll usually start with the “low-level” items – think scarves, watches, or perfume. Over time, by buying consistently, you build a relationship with your local boutique and the staff.

At some point, you might get offered your first bag. Not a Birkin or a Kelly, of course, but one of the less prestigious lines. This whole sales approach has come under some scrutiny by now. And that’s not exactly a surprise. It’s completely counterintuitive that you walk into a store, willing and financially able to buy the product, and the store basically goes, “Nope, you can’t buy that.”

There was a U.S. class action lawsuit against Hermès over this. The argument was that this “pay-to-play” system, in which you’re nudged to buy other Hermès products first to build a purchase history, with no guarantee you’ll ever be offered a bag, constitutes an illegal tying arrangement under antitrust law.

Hermès argued that handmade Birkin or Kelly bags are scarce and therefore that allocating them to loyal clients is a selective retail practice. Hermès has won the case, and as a complete layman in law with only a dozen law lectures at University, it does make sense to me that Hermès has full control over whom they sell to. The fact that something is displayed in a store, even if there’s a price tag, does not constitute an official offer to sell the item to anyone who shows up.

Before we go further into why gaiting is such an important mechanism for Hermès, let’s first discuss Hermès's manufacturing process and see whether Birkin bags are actually so scarce that Hermès couldn’t offer more, even if they wanted to.

Manufacturing Excellence

Of course, that’s only part of the truth. Hermès could produce more bags if it wanted to. But that doesn’t take away from how demanding and genuinely high-quality the manufacturing process is.

Hermès follows the so-called “one man, one bag” policy, meaning each bag is made by a single artisan from start to finish. Shawn joked in our episode that Adam Smith wouldn’t be proud of that, and he’s probably right. But that’s exactly what makes Hermès special. Every bag is produced in France, and a single artisan manufactures and assembles it.

So each bag is essentially a 1-of-1, marked with specific stamps that identify the artisan and trace the leather's origin. And by the way, when Hermès products say “Made in France,” they’re actually made in France. Not just the final stitch or “assembled in” part, but the whole thing.

Today, that’s not a given anymore, even among luxury brands. It’s a real part of the Hermès brand image. Roughly 80% of products are manufactured in France. And the other 20% isn’t outsourced to low-cost Asian countries, but to places that are genuinely specialized in those categories. For example, watches are made in Switzerland, and some clothing comes from Italy.

Training to become an artisan takes about 18 months. But to become a Master of the craft, and yes, there’s an actual certificate for that title, you’re looking at roughly five years of study/work.

What I found even more astonishing is the so-called “apprentice tradition.” Hermès family members have to spend at least a decade in production before they can take an executive position. So this isn’t a little internship, so you can later say you “understand the company on all levels” in a Wall Street interview. They have to commit their lives to the craft in order to lead the company one day.

We’ve definitely not seen anything like that with Bernard Arnault’s kids at LVMH or really at any other company we’ve ever looked at.

By the way, Hermès is currently run by the sixth generation of the family. Although they no longer carry the Hermès name. At some point, there were only daughters with the Hermès name, and since, traditionally, the wife took the husband’s name, the Hermès name didn’t make it.

Business Breakdown and Store Economics

Up until the ’80s, almost all of Hermès’ revenue came from France, and roughly 50% of sales were driven by the Silk & Textiles segment – ties, scarves, shirts, that kind of stuff. Today, that picture has flipped completely, like with pretty much every modern global brand.

Roughly half of revenue now comes from the Asia-Pacific region, with China as the largest market. Around 20% comes from Europe, another ~20% from the Americas, and about 10% from Japan.

It’s not news to anyone, but I still find it kind of wild how critical Asia has become for fashion and luxury. It used to be Europe or the U.S., and now that era is long gone. If your brand doesn’t work in China, you’re in a tough spot.

The good news for Hermès is that it’s one of the most popular brands among the Asian elite, if not the most.

Asia isn’t just a volume story, either. It’s also the highest-margin region globally. While operating margins in Europe and the U.S. tend to sit somewhere in the low-to-high 30s, China is closer to 50%. The main reason is simply that demand from Chinese clients is huge. So every store you allocate to that region has a very high probability of selling through quickly.

Imagine that at any given time, you have 100 high-quality customers in Paris that you’d like to sell a Birkin to. You can’t allocate much more than ~100 bags without hurting the exclusivity.

Now take a store in China that’s roughly the same size and has roughly the same staffing. But instead of 100 top-tier clients, it might have ten times that number on the list. We don’t need to study math to see why that’s a more profitable store.

The more demand there is per store, the easier it is to be selective and still sell out.

I did some math using the (pretty limited) details Hermès reports, and I don’t think it’s unreasonable to assume Hermès generates about €60,000 to €80,000 per square meter on average. Which is an insane number.

Other fashion retailers like Lululemon sit around $16,000, while luxury fashion brands tend to be closer to $30,000 to $40,000. Apple is often crowned the king of store economics at roughly $50,000–$60,000, and it’s totally reasonable to think Hermès is in that same league, if not higher.

What has accelerated this metric is that Hermès’ share count has been shrinking for quite some time now. Since peaking in 2019, the store count has declined from 311 to 293. At the same time, revenue compounded at roughly 17% per year.

This is possible because of the sales dynamics I described above, and we’ve also seen it with Ferrari.

First of all, Hermès stores are basically never crowded. Employees have time, and big purchases are often initiated through personal outreach. So clients are contacted and invited. So “more stores” doesn’t automatically translate into more high-ticket sales the way it would for a normal retailer.

And because Hermès is the one doing the inviting, the most important locations are the flagship stores. You don’t need a bunch of boutiques in Tier 2 cities just so people can casually pop in while they’re out shopping. The customer will go to the city where Hermès is. Hermès doesn’t follow them.

Guy Spier once made a similar point about Ferrari. Most luxury car brands fight for the prime, easy-to-access spot in town. Ferrari doesn’t really care. They know the customer will come to them anyway. If there’s no real substitute for what you sell, you don’t have to chase customers.

Structural Tailwinds

The Chinese luxury market has been slow in recent quarters, affecting not only Hermès but the entire luxury sector. In fact, there are long-term tailwinds that could benefit Hermès.

If we want to figure out whether Hermès can still be a great long-term investment, we need to know two things: First, what does the runway look like? And second, what are the risks that could actually kill the brand?

On the runway side, there’s not much to lose sleep over. Hermès has been at the forefront of ultra-high-end luxury for close to two centuries, and if anything, the client base is still expanding. The top 0.1% has been the fastest-growing cohort of luxury shoppers, compounding at around 9% per year over the last decade. For comparison, aspirational shoppers grew at a CAGR of only 1%.

I also don’t really see major headwinds from a generational shift. Studies suggest Gen Z is at least as interested in luxury as prior generations, if not more so. And when people say younger consumers prioritize travel over physical goods, it’s worth remembering who Hermès is actually selling to. If you can drop tens of thousands on a bag, odds are you’re not cancelling the next vacation to “make up for it.”

Another, somewhat unusual but really important, tailwind for Hermès is its family ownership. Luxury brands can fail for all sorts of reasons, but the most common is that they lose sight of the long term in pursuit of short-term performance. More often than not, that drift happens under the watch of outside CEOs.

As long as Hermès stays family-controlled and I fully expect that to be the case for a very(!) long time, I see that particular risk as relatively low.

Capital Allocation – Dividends and Hoarding Cash

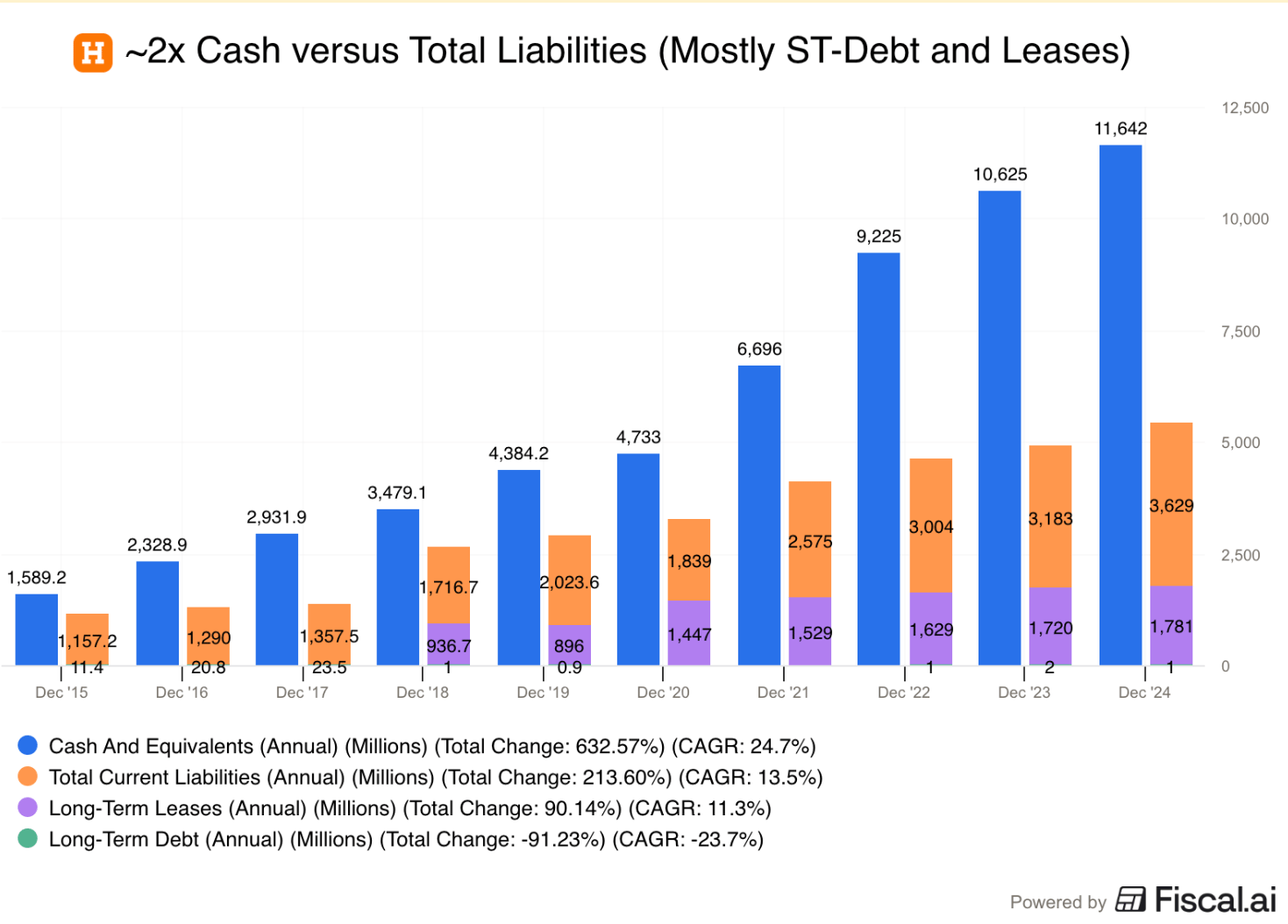

When evaluating companies, we love to see a strong, healthy balance sheet. Hermès definitely checks that box. Cash is about twice the total liabilities, which mostly consist of short-term debt and leases, so no long-term debt.

While that’s great to see, you could argue it also hints at something else. Hermès may not have endless opportunities to reinvest capital at high returns. Don’t get me wrong, the money it can reinvest earns phenomenal returns. We’re talking ROICs in the 40s. But there’s a ceiling on how much capital you can realistically plow back into the business.

That’s why cash compounded at roughly a 25% CAGR over the past decade. At today’s valuation, though, there isn’t an easy “fix” for that. Shawn and I talked about this in our Ferrari episode. When the multiple is high, spending cash on buybacks or dividends is simply less efficient.

Last year, Hermès paid about €1.6 billion in regular dividends and another €1 billion in special dividends. And despite that, the dividend yield still came in below 1%.

Valuation and Investment Decision

I could give you a song and a dance about different growth rates across product categories, but I think that would miss the real driver of Hermès’ stock price. At almost 50x earnings, the multiple is what’s going to decide your investment success from here on out.

Hermès is probably the most durable business I’ve ever come across. The brand and its image have existed for almost two centuries, and I don’t see that changing. In my mind, it’s even more durable than Ferrari. With Ferrari, you can at least get creative and paint a bearish picture around a structural decline in ICE car sales. Ferraris would still be in demand among the super-rich, sure—but it could still hit volumes over time, and that matters.

I don’t see a comparable structural risk with Hermès. The main risk is reputation. You could imagine some kind of scandal around sourcing—where the leather comes from, animal welfare, that sort of thing. But Hermès seems to manage this pretty proactively (for example, by controlling parts of the supply chain and working with dedicated farms), so I’m not losing sleep over it.

I also don’t really worry about Hermès suddenly being “out of fashion.” It doesn’t chase trends, which makes it unusually resilient in a world where fashion can flip overnight. And even if today’s icons like the Birkin or Kelly ever lost some of their appeal, Hermès can create the next product that benefits from the same brand prestige. Don’t forget that back in the ’80s, leather goods were only a small part of the business. Reinvention and innovation are part of the Hermès story.

With that backdrop, let’s get into the model. In my base case, I assume revenue grows at an 8% CAGR, a couple of percentage points below what we’ve seen in the last few years. I keep margins stable at current levels, which means operating profit and net income grow at roughly the same pace.

At an exit multiple of 40x and a 20% margin of safety, that leaves us with an estimated fair value of about €1,850, and only a mid-single-digit expected return.

In the bull case, I’m more optimistic about growth. Instead of a slowdown, you get more of a rebound in the Chinese luxury market over the next five years, which doesn’t just lift volumes, but also improves the mix and margins. In that scenario, I end up with roughly 14.5% growth in net income. Assuming the same multiple and the same margin of safety, this yields an estimated fair value of around €2,750.

You might ask why I don’t increase the multiple in my bull case, and this is where investing in Hermès gets tricky for me. As a value investor, I’m simply not willing to expand a multiple that’s already 40x (in my model). If anything, and you’ll see this in the bear case, I compress it.

Hermès might trade at the current ~50x for a while. But to me, at that level, you’re mostly looking at downside risk. Even one of the best companies in the world will, at some point, see its multiple come down.

And when that happens, as you’ll see below, it doesn’t take much to end up with a stock that’s trading 50% lower than today.

Hermès is a wonderful business, but we’re in a similar situation to Ferrari back when Shawn covered it on the show: at some point, the price is simply too high. And in my opinion, the stock is priced too well right now.

If we ever get a chance to buy Hermès at 30x earnings, I’m all for it. And if the past few weeks have shown us anything, it’s that even the best companies go on massive “sales” every now and then.

For more on Hermès, you can listen to our podcast here.

More updates on our Intrinsic Value Portfolio below 👇

Weekly Update: The Intrinsic Value Portfolio

Notes

PayPal released earnings, and they were a dumpster fire — basically the complete opposite of Q3. This reflection will take up a bit more space than usual in the Notes section, but I think that’s warranted after we discussed the position in detail over the last few days in our Intrinsic Value Community and after we decided to sell our PayPal position.

Instead of doing a detailed rundown of the quarter, I want to walk you through my thought process on PayPal. If you have questions about the numbers, drop a comment, and I’ll make sure to work through them and answer.

The most important thing upfront: we decided to sell PayPal after earnings. This wasn’t an emotional decision. I had a checklist going into the print of what I would need to see to stay invested. Over the last two months, I saw a lot of yellow flags, and my mistake was not acting on them sooner.

The main issue is my loss of trust in the management team. After Q3 — which was way better than I expected, frankly — shareholder communication got increasingly worse. There were no real updates or follow-ups on major initiatives like ads, Fastlane, or PayPal World. As you know from the original pitch, these initiatives were the optionality of the thesis. And when we did get disclosures, they felt less like transparency and more like empty numbers or narratives.

Black Friday is a good example. Instead of giving shareholders TPV data, we got “transactions per minute.” Instead of precise BNPL growth, we were told it was “double digits.” For a segment where the key question is whether growth is closer to 10% or 30%, that’s not useful information. It’s avoiding information. And this wasn’t a one-off. It became a pattern.

Another example followed with this earnings release: the surprisingly abrupt firing of CEO Alex Chriss and the little clarity shareholders got on the “why.” Execution hasn’t been good, no doubt. But spending the last two months in public appearances blaming macro, and then turning around and removing the CEO because of execution… that’s not a great look.

The new CEO, Enrique Lores, comes from HP and has served on PayPal's board. He seems to be known for streamlining operations. That can help in the short term. But PayPal isn’t losing because it’s spending too much on overhead. It’s getting left behind by competitors. It doesn’t need a pure cost-cutter. More than anything, it needs a clear vision and someone who can execute on it.

I thought Alex Chriss was that guy. I was wrong. And maybe he also wasn’t given enough time by the board — but honestly, that would be an additional argument for not owning the stock. It’s like sports: with the wrong management team and culture at the top, you can’t expect the team to perform, no matter how much potential the roster has.

Even the guidance doesn’t sit right with me. PayPal is guiding for another year of $6 billion in buybacks, which at today’s market cap is roughly a 15% buyback yield. And despite that, they’re guiding EPS down mid-single digits. Without more detail on what exactly they’re investing in, and how much, I have to assume that organic earnings power is declining meaningfully to make that math work.

Yes, PayPal is cheap. But “cheap” alone isn’t an investment thesis for me. The optionality I was underwriting is largely gone, trust is lost, and the core checkout business seems to be losing ground faster than expected. Which is especially surprising to me after solid results just last quarter.

A slow-growing stock at a cheap multiple with upside optionality is one thing. But once the business starts to decline structurally, no margin of safety is large enough to compensate for the uncertainty. I can’t predict if there will be a short-term bounce or whether the new CEO can actually turn the ship around. I do know that the PayPal of today is on my too-hard pile. And with other investment opportunities coming up, I don’t think my money is best invested in PayPal.

Uber reported earnings as well. And while the market initially didn’t like it, the underlying results are fully in line with our thesis and show strong fundamentals.

Zooming out is everything with Uber. After first attaining profitability in 2023, operating profit margins have gone from 2% —> 6% —> 10.7% (and 12% in Q4) over the last few years. From 2024 to 2025, nearly doubling operating profit margins + 18% revenue growth led to 100% growth in operating profit for the year!

After the Pandemic propelled the business to incredible growth, rather than seeing a pullback, Uber’s growth is continuing to accelerate: sales up 16% in 2023, up 17% in 2024, and now up 18% yoy in 2025.

We continue to believe that we’re early in the Uber story, and operating leverage is very much still kicking into full effect. Between AVs, advertising, and simply further scale, we have a lot of confidence in margins continuing to rise dramatically in the coming years, while Uber’s valuation itself seems incredibly reasonable to us, given their prospects, at sub 28x EV/EBIT.

We were also happy to see that Uber’s subscription membership program, Uber One, grew 55% YoY, reaching 46 million paid subscribers globally.

Long story short, we just freed up capital by liquidating PayPal, and we decided to put these funds into Uber. Thus, the position will increase from slightly below 7% to 10%.

Reddit reported another set of impressive earnings. Although the market didn’t really know what to do with it. After pushing the stock 10% higher initially, the stock went back negative, only to end up slightly in the green. Aftermarket trading is crazy…

In the end, Reddit sold off 8% the next day, and we took this as an opportunity to finally add to our position. Reddit has been too expensive for a while, but now it has run back a lot. We decided to take it up from 2.7% to 4%.

Revenue was up 69% overall and 76% internationally. Net income margins, from 2024 to 2025, inflected positively by more than 50 percentage points, from -37.2% to 24.1%. That is astounding. And because profitability was lower earlier in the year, the number is a bit weighted down. In Q4, net margins hit 34.7%.

Dilution has been one of the core issues post-IPO for me with Reddit, so it’s wonderful to see them already announcing a $1b buyback program.

Daily active users is up 19% YoY, and weekly active users is up 24% YoY. This is pretty solid, though for RDDT to be a 10-bagger for us one day, we’re going to need to see that kind of user base growth sustained for many more years. The reason revenues are growing so much faster than the user base is, namely, due to Reddit historically having low ARPU monetization. As the user base grows, while revenue per user increases significantly, that’s a recipe for exploding top-line figures, which we’ve seen, also leading to exploding margins, causing profits to grow even faster.

Quote of the Day

"Never buy what you don’t want, because it will be dear to you.”

— Thomas Jefferson

What Else We’re Into

📺 WATCH: Prof G Podcast on Google, the Netflix-WBD Deal, and Software Stocks

🎧 LISTEN: Gavin Baker on The Economics of AI and the Threat for Software

📖 READ: A Case Study on one of Buffett’s earliest Investments ever by Joe Raymond

You can also read our archive of past Intrinsic Value breakdowns, in case you’ve missed any, here — we’ve covered companies ranging from Alphabet to Airbnb, AutoZone, Nintendo, John Deere, Coupang, and more!

Do you agree with the investment decision on Hermès?Write a comment to elaborate! |

See you next time!

Enjoy reading this newsletter? Forward it to a friend.

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here.

Join the waitlist for our Intrinsic Value Community of investors

Shawn & Daniel use Fiscal.ai for every company they research — use their referral link to get started with a 15% discount!

Use the promo code STOCKS15 at checkout for 15% off our popular course “How To Get Started With Stocks.”

Follow us on Twitter.

Read our full archive of Intrinsic Value Breakdowns here

Keep an eye on your inbox for our newsletters on Sundays. If you have any feedback for us, simply respond to this email or message [email protected].

What did you think of today's newsletter? |

All the best,

© The Investor's Podcast Network content is for educational purposes only. The calculators, videos, recommendations, and general investment ideas are not to be actioned with real money. Contact a professional and certified financial advisor before making any financial decisions. No one at The Investor's Podcast Network are professional money managers or financial advisors. The Investor’s Podcast Network and parent companies that own The Investor’s Podcast Network are not responsible for financial decisions made from using the materials provided in this email or on the website.