- The Intrinsic Value Newsletter

- Posts

- 🎙️ FICO: The Algo Behind America's Credit

🎙️ FICO: The Algo Behind America's Credit

[Just 5 minutes to read]

Every year, Fair Isaac Corporation ($FICO) sells over 10 billion scores annually — four times the number of burgers sold by McDonald’s, and twice the number of coffees that Starbucks sells.

In a system where nine out of ten lending decisions lean on one number, that number quietly runs modern American life, considering that everything from job interviews to apartment applications can also involve pulling someone’s FICO score.

This is the story behind that three-digit number that can determine which credit cards you’re approved for and the interest rate on your mortgage (or whether you qualify for one in the first place), as well as the wide-moated ‘tollbooth’ business that charges a tiny fee each time your credit rating is passed on.

— Shawn

FICO: The Algorithm Behind America’s Lending

When you apply for a mortgage, your lender doesn’t just “check your credit.” They buy a score, often multiple scores, from the big three bureaus (Experian, TransUnion, Equifax), who in turn remit a royalty back to FICO for having been the one to synthesize the underlying credit data into a single rating.

Beyond its practicality for lending decisions, that score is also the stamp that enables your local bank to sell the loan onward to investors, following a government guarantee from Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac (who have long required FICO scores for the mortgages they ordain, too.)

As such, the securitization machine and capital markets more broadly want a standard gauge for risk: one yardstick so loans can be pooled, sliced, and priced.

FICO is at the heart of mortgage loans, and then the repackaging of them into mortgage-backed securities sold to investors

FICO is that yardstick, and that sort of monopoly-like positioning is exactly what we want to see from potential investments, as Daniel and I consider whether they can continue to generate excess returns on capital for many years to come. On that front, FICO’s stats are very impressive: 38%+ average ROIC in the past 5 years, 12% revenue growth per year for the past three years, 40% free cash flow margins, and a 10-year EPS CAGR of 25%(!)

This is no secret, though. Many investors are keenly aware of FICO’s significant and unwavering role in these processes. It often rates high on the list for people’s “Top Quality-Stock Ideas,” meaning the stock trades consistently at a substantial premium to the median S&P 500 company.

Correspondingly, the stock has been a juggernaut of a compounder:

This was prior to the October 1st rally in the shares (more on that later)

Yet, the less understood wrinkle is that, within the eye-watering amounts you pay at closing for titling, taxes, and commissions, usually in the thousands of dollars when all is said and done, the FICO piece can be just a few dollars — a rounding error in cost but also essential to the process. An analogy with Visa is apt: merchants wince at the tolls they pay to Visa, but the network’s utility is so overwhelming that the small toll persists. There’s good reason to think that FICO could be squeezing much more juice than they currently do, adding incremental revenues that almost entirely drop to the bottom line.

Through a different lens, if you’re a policymaker trying to meaningfully lower the cost of buying a home, shaving FICO’s pea-sized fee, no matter how monopolistic it is, really doesn’t move the needle. You’ll get more leverage tackling title costs or broker-commission structures. Meanwhile, the market continues to pay for the numbers (FICO scores) that keep the machine moving.

The cost for pulling a FICO score as part of the mortgage origination process is $4.95, which, again, isn’t a lot in the context of overall closing costs. FICO could conceivably double, triple, or quadruple that price, as they already have in recent years, without anyone flinching, allowing them to easily double, triple, or quadruple their mortgage-origination revenues (which are a substantial part of the overall business).

From Lending Pseudosciences to Standardization

Before FICO, lending was vibes-based, in Gen Z parlance. You shook a banker’s hand and hoped they liked your story. Rates were one-size-fits-all; truly great credits couldn’t prove their greatness, and risky borrowers were often shut out entirely. It wasn’t just inefficient, but all too often, discriminatory, as well. Credit decisions could hinge on subjective cues that had nothing to do with the probability you’d actually pay the loan back, ranging from someone’s marital status, skin color, gender, and even involvement in the Church.

Decisions about extending credit were, in many ways, being made subjectively based on things that had nothing to do with one’s objective creditworthiness, since neither the data nor the algorithms to objectively integrate that data existed at scale.

Enter Bill Fair and Earl Isaac, who met at the Stanford Research Institute and in 1956 launched a shoestring consulting firm built on a simple idea that now sounds obvious: use data (properly) to make better decisions.

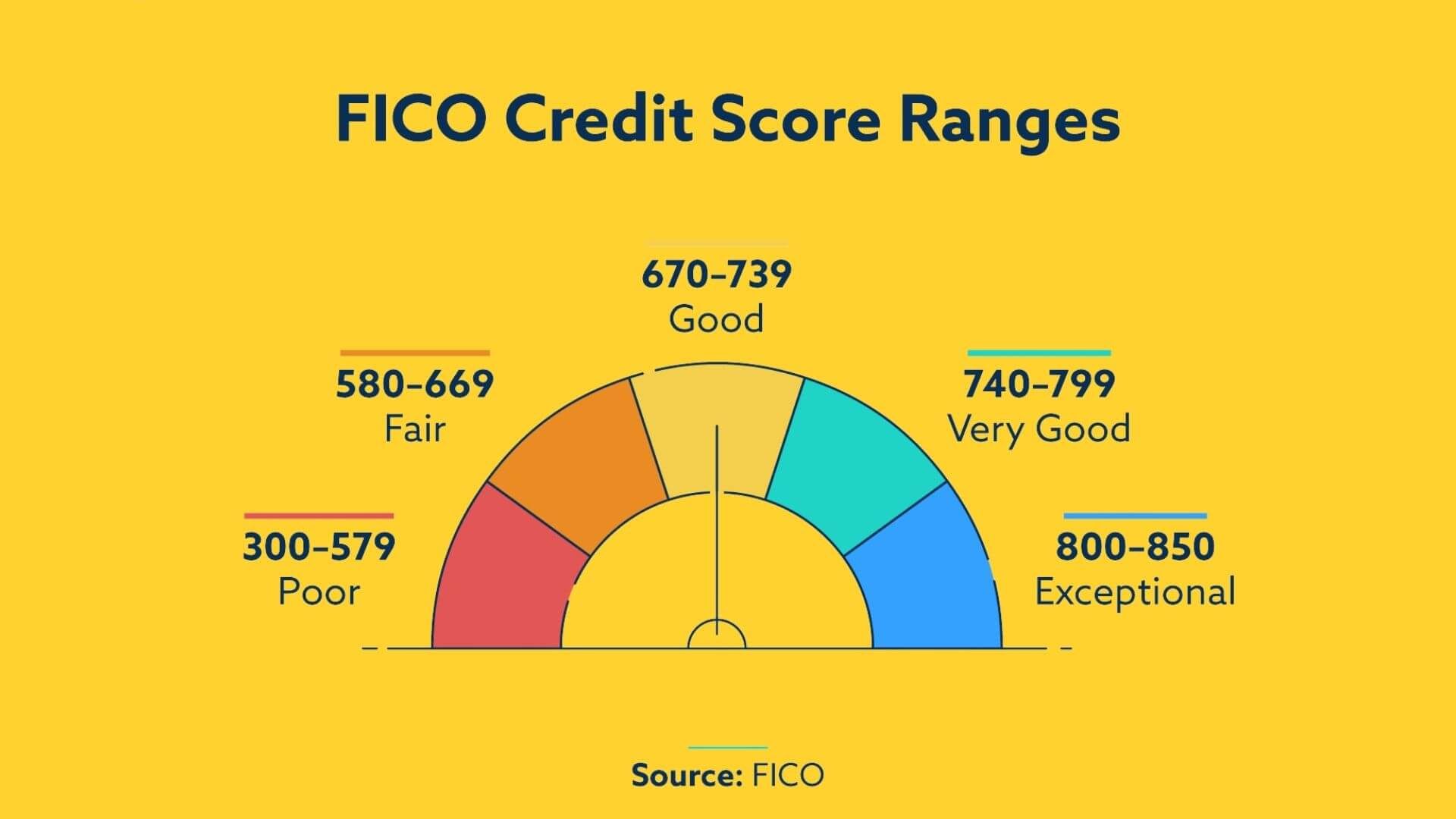

These early scoring systems they designed were bespoke, though, built for individual institutions. The pieces didn’t click into a true standard until the credit bureaus consolidated in the ’70s and ’80s, with FICO releasing “PreScore” in 1981, which led to the now-familiar 300–850 FICO Score in 1989. However, the watershed moment was six years later, when Fannie and Freddie required FICO scores for all conforming mortgages (i.e., mortgages that can be sold to Fannie & Freddie), thereby cementing FICO as a lingua franca of risk.

That mandate didn’t so much arbitrarily confer a government-backed monopoly on FICO as it turned FICO’s strong position and adoption amongst lenders into the de facto industry standard.

Think about the coordination benefits of having a universal scoring standard: if you ran a handful of branches for some regional bank in 1950, a universal scale for credit risk would let you compare risk across geographies, products, and time in assessing your company’s overall risk profile to an extent that never otherwise would’ve been possible.

Now, extend that to Wall Street, which trades baskets of loans by the billions — grading those loans with a common scoring system was, and is, essential for standardizing trading. In other words, standardization didn’t just make lending decisions fairer at the local banking level; it expanded the market by letting everyone price risk with a common ruler.

It’s sort of like how, for better or worse, the SAT score has become a necessary part of comparing and contrasting thousands of students annually in a given college’s admissions process. For everything wrong with the SAT, and excess reliance on it in the American academic system, you can imagine how a universal scoring system makes life easier for administrators who would otherwise be left to more subjective means for determining which applicants are admitted and which aren’t.

For starters, if every school relied only on its own proprietary scoring system, it would be impossible to compare how a university’s student body compares to other universities. Is the median SAT score to get into Duke higher or lower than that of UNC-Chapel Hill? Nobody would know, which is to say, internally and externally, the ability to objectively (as much as possible) compare the academic merits of one university with another would largely be lost without any kind of uniform standard, whether that standard is the SAT or something else.

The existence of a standard is necessary, and it just so happens to be very difficult to move off a standard once it has become, well, a standard (good for FICO’s business!)

What’s Inside a Score

A FICO Score isn’t entirely a black box. It’s a mathematical formula mapping five buckets: payment history, amounts owed, length of credit, mix of credit, and recent credit, to a single probability of default. The key is whether it can reliably separate higher-risk borrowers from lower-risk borrowers across an economy. Decades of loss data say yes, which is why the market keeps using FICO scores as a proven standard.

FICO score inputs

But there are implications to any scoring system that implicitly favors some over others, especially in a country that didn’t have equal rights at a federal level until approximately 60 years ago.

If you were shut out of mortgages for decades, you couldn’t build the length of your credit history, which is now a pillar of your FICO score.

Despite potentially reflecting a consistent record of paying owed amounts, rental payment history isn’t usually counted in FICO scores, while mortgage payments are. Again, if your family was discrimminated against in getting a home loan 80 years ago, that can compound and ripple through ‘til today, leaving folks stuck in a cycle of rentership that doesn’t add to their credit score and their ability to ultimately build wealth through homeownership, hence claims that, even still, the FICO score isn’t a perfectly fair benchmark, despite being calculated, in theory, with inputs that are meant to be objective.

That’s where VantageScore, a joint venture launched by the three major credit bureaus (Experian, TransUnion, and Equifax) as FICO’s sole competitor of substance, has pushed into the picture, offering the possibility to calculate credit ratings for more types of people with nontraditional data like rental and utility payments, seemingly opening the door for access to credit to ~tens of millions~ of people in the U.S.

FICO’s response acknowledges that it’s a neat idea, but credit scores aren’t just about scoring as many people as possible; it’s about accurately predicting who is more and less likely to default over time, which undermines the decision to make a loan and at what interest rate. Inclusivity is a goal, but predictive power is the job, and by all measures, FICO’s latest models remain by far the predictive credit scoring metrics, perpetuating its deeply-rooted usage (while FICO also explores using more types of data inputs).

Whether you side with one or the other, the scoreboard doesn’t lie. Almost two decades after its launch, VantageScore hasn’t dislodged FICO’s position with lenders in any meaningful way.

And even in places that lean on alternative models for underwriting, you’ll often find FICO lingering in their communications — FICO scores are still the number they use in investor decks to describe loan pools because it’s the number everyone understands. Said differently: when a lender doesn’t explicitly pull FICO scores as part of their loan underwriting decision, they still pull them to share with 3rd-parties, since FICO scores are a common tongue understood across regulators, investors, and customers.

The Network Effect Affecting Your Financials

The thing with industry standards is that they tend to harden over time, making for as wide a moat around FICO as any business we’ve seen (perhaps with the exception of VeriSign, which earns annual royalties from every website ending in “.com” around the world. Here’s our previous newsletter on VeriSign if you missed it.)

Lenders use these scores by setting approval cutoffs based on FICO score bands. Then, when mortgages are packaged into mortgage-backed securities and sold, investors demand the average FICO score for these securities to assess their riskiness.

And consumers, so you and I, may check their FICO score (or estimates of it) before opening a card or shopping for a home to know what they qualify for. Point being, a number of different parties independently rely on the objectivity and trustworthiness of FICO scores.

In fact, over 95% of U.S. mortgage and credit card securitizations reference FICO scores somewhere in the process. That’s more than a dominant market share(!), that’s the type of monopoly-like dominance you see in government-regulated utilities. FICO, though, isn’t subjected to the same regulated returns as utilities.

Even if a competitor is “as good” or even a hair better than FICO on raw risk-modeling performance, swapping out a common yardstick changes the calculation of credit risk distributions and the translation table for interpreting those scores that the whole market speaks. Put plainly, a competitor has to have a significantly better formula for predicting credit risk across society; otherwise, inertia favors FICO.

Of course, the more a system leans on a standard, the more it attracts scrutiny.

Under the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s (FHFA) Bill Pulte, conforming mortgages (those compliant with Fannie & Freddie standards) are moving toward a world where lenders can use either FICO or VantageScore 4.0 instead of a model where FICO was effectively solely mandated for years.

If your first reaction is “that sounds big,” you’re right; Daniel felt the same. That’s why FICO shares sold off hard on the headline, but remember that the driver of the economic engine here is the actual number of scores pulled (and the prices paid for those scores).

Optionality can open the door to competition, but it doesn’t automatically mean everyone (or anyone) will shift away from FICO if it’s working well, as it has. That’s not to say, though, that there isn’t a good reason to worry about whether this will make it more challenging for FICO to raise prices in the future.

Still, it’s worth emphasizing two things:

Underwriting share ≠ usage share. Big banks may blend internal signals with bureau data, but that doesn’t mean they stop pulling (or reporting on) FICO. Like colleges considering all the different factors in a student’s application, with each school having its own weighting system, they still use SAT scores as an input, and that’s unlikely to change, even if FICO scores or SAT scores were to become a smaller part of the overall decision-making process.

Even if the scores are relied on less in making final decisions, as long as they’re still useful enough to be pulled (paid for), then that’s what ultimately matters for FICO (and the SAT).

On that point, JPMorgan and Bank of America absolutely use more internal data than they did ten years ago, leading some to wrongly assume that FICO is being phased out. But again, using more data sources is different from not pulling FICO at all. And, as mentioned, banks still reference FICO all over their own disclosures; even when lenders don’t underwrite with FICO, they often communicate with it. Toyota’s financing arm, for example, underwrites with VantageScore but still describes its lending book to investors using FICO.

Cost vs. consequence. In most cases, outside of mortgages, a FICO pull costs pennies to dollars, while a mispriced loan can cause six, seven, or eight figures of pain. There’s an asymmetry here — FICO’s relatively tiny tolls can sustainably persist when the alternative risks breaking the business (nobody at a bank wants to lose their job because they pushed to move off using something as inconsequential in cost as a FICO score if that were to precipitate an increase in lending losses).

I think people underestimate the number of business decisions, small and large, that are made using some permutation of this logic, boiling down to “let me keep doing this since it’s always what we’ve done” or “I’ll just do what everyone else is doing” as excuses for perpetuating the status quo. And to be clear, those mindsets greatly enrich FICO.

How a Low Price Built a High Wall

One interesting aspect of this story is that, for decades, FICO kept prices low and unchanged. That was part of a strategy to lower the frictions to widespread adoption as much as possible.

The playbook was to make FICO the default through low-cost and predictive superiority, driving the industry to build integrations, workflows, and securities around it, and only then test the price lever after 25+ years of patience. By the time the system “spoke FICO” end to end, price hikes would be unlikely to trigger defection (just grumbling), and that’s exactly what happened in 2018.

Mortgage score prices rose 30%…then more…then even more. Now, FICO’s wholesale mortgage fee has risen to $4.95 from 2018 levels — a 725% step-up.

Even though the number of people applying for mortgages, auto loans, or credit cards hasn’t dramatically changed in the last few years, price hikes have enabled double-digit compounding of the top line, while earnings per share have compounded even faster as profit margins have expanded (since there are virtually no incremental costs to just raising the prices for FICO scores) and from those profits being recycled into share repurchses, reducing the denominator in EPS.

See below, earnings per share since 2019 have compounded at roughly triple the rate of revenues:

As you can probably guess, this is what caught Bill Pulte of the FHFA and also Congress’s attention, with politicians like Elizabeth Warren highlighting the issue. As FICO leaned in, the DOJ opened an antitrust probe, the FHFA rewrote conforming mortgage rules, and Congress started asking questions.

You can argue management “flew below the radar” for 25 years and then turned on the high beams overnight, and while shareholders have cheered the stock higher, regulators have noticed, which is, as far as I can tell, the bear case against an otherwise bulletproof business.

Two Business Engines, Very Different Torque (Margins)

With all this talk about credit scores, you might be surprised that FICO’s top line splits roughly 50/50 between Scores and Software.

And the disproportionate amount of attention on one over the other is because, with the bottom line, the contribution isn’t remotely 50/50. The Scores segment, our main focus thus far, generates over 75% of the company’s operating income due to having much higher profit margins. So, Software is the other half of FICO’s revenues, but a fraction of the total profit.

Ironically, software segments are usually the most profitable part of the business for many companies today, so this inversion isn’t from FICO’s Software unit being particularly poorly run, but more so due to how extraordinary the core scores franchise is.

What’s in “Software”, you ask? Think of a toolbox that sits around the score, including fraud detection, origination workflow, collections, and comms (SMS/email for alerts and reminders). The platform lets lenders embed decision-making logic without hard-coding rules in 40 places. And yes, it leans on the same data the scores do, but it’s a distinct product line facilitating optimal usage of FICO scores, you might say.

Software still posts 30%+ operating margins, making it a very good business by any normal standard, but the Scores business lives on a different planet with nearly 90% operating profit margins. When your COGS is just a math algorithm developed decades ago, price rises mostly fall straight to the bottom line.

A Note On Cyclicality

An important question for us to ponder when considering FICO’s intrinsic value is where the company is more cyclical than it looks. The answer to that is, unequivocally, yes.

That’s a bit peculiar for a company that many refer to as a “Quality Compounder,” which usually means the business seemingly grows in almost a straight line over time. For FICO, volumes naturally ebb and flow with credit activity across the economy, but the business hasn’t been as sensitive to this as you’d think. While the business can make money in both high and low-rate environments, the massive price hikes of the last few years have concealed any underlying fluctuations in the number of scores being pulled by lenders for lending decisions (mortgage applications, credit card applications, auto loan applications, etc).

At the core of this thesis is your opinion on how much further FICO can take price? Can they triple or quadruple prices over the next five years? If so, I can tell you without even doing a valuation that the stock is undervalued and will do very well.

But if regulators, and VantageScore, cause FICO’s management to begin taking price much more conservatively in, say, 18 months from now, then the company’s earnings power would seemingly be much lower than implied by the market at the stock’s current P/E of 72x trailing earnings (more than three times the S&P 500’s P/E multiple), with the business becoming much more cyclical in the future, tied to swings in credit activity.

Now, volumes could actually be a tailwind if/when price-taking slows. FICO’s CEO recently suggested that mortgage loan origination is ~40% below peak (as home prices and rates remain elevated), which, if/when rates drift down, could drive more volumes for the company, kicking the can on needing to take price as aggressively in the short-term to keep up with the market’s earnings expectations.

But the skeptics would say you can’t run the 2018 playbook again at the same intensity. Regulators are watching, and after 25 years of no price hikes, it’s hard to argue that FICO hasn’t now compensated for that. Yet, there’s no guarantee that mortgage borrowing will pick up soon, and it’s quite plausible that mortgage origination could decline further.

For Scores revenue to double again in the next five years, you’re implicitly assuming hefty price hikes on top of volume normalization, which is possible, but I’m not certain about it so much that I’m content paying 70x earnings for the stock.

Talking Valuation

Those points lead me to the part where I tell you what I personally think is a fair price to pay for this wonderful business, and the decision on whether to add it to our Intrinsic Value Portfolio, though you can probably guess that I’m going to need to see the stock come down further before I endorse it to Daniel.

Let’s begin by contrasting FICO with other wide-moat tollroad financial services businesses, where FICO’s valuation still looks to be at a premium:

P/E Valuations: Moody’s (Blue), FICO (orange), Visa (purple), S&P Global (green)

S&P Global and Moody’s, in providing credit ratings for securities and corporate (and governmental) borrowers, actually have a relatively similar business to FICO in a sense, though a more capital-intensive one — more ongoing qualitative work goes into monitoring corporate credit ratings compared with just plugging in data inputs as they come for the masses of individual borrowers.

That, and the presumably untapped pricing power still on the table for FICO, which allows them to plausibly grow faster than these more mature peers, does justify a higher valuation, so the question is really determining what’s a fair price to pay for such a quality, and fast-growing, business.

Of the four comps I show in the chart above, Visa’s business is arguably the most mature, and the P/E reflects that (Daniel pitched Visa a few months back, actually). I’d probably say that neither Moody’s nor S&P Global has much of a margin of safety built into them today, while Visa’s valuation is much more reasonable as a low-30s multiple of earnings, reflecting the company’s ability to generate excess returns on capital for the foreseeable future, allowing them to grow earnings per share modestly faster than the overall market.

In a scenario where FICO roughly doubles earnings per share through 2030, as many analysts expect, the implied CAGR would be roughly 15%, thanks to price hikes in scores, organic growth in software, and share repurchases (the company has shrunk its share count by 3% a year since 2019).

According to Ben Graham (Warren Buffett’s mentor), his P/E valuation matrix suggests that when the AAA corporate bond yield is 5% (the opportunity cost of an equity investment), we should pay ~33.9x earnings for a stock that we think can grow at 15% a year over 5 years, and 15% EPS growth through 2030, as mentioned, is roughly the consensus on Wall Street for FICO currently.

And well, with the AAA-corporate bond yield being approximately 5.5%, that places us squarely between the 5%-bond-yield P/E recommendation of 33.9x and 6%, where the recommended P/E is 28.2x.

See for yourself below:

Point being, even if Wall Street isn’t being overly optimistic about the base case for FICO’s earnings growth over the next 5 years (driven by Scores’ price hikes), the market is still paying too much of a premium for this growth.

I don’t have a hard opinion that FICO can’t double its earnings per share over the next 5 years, but even so, the market has seemingly taken its enthusiasm beyond a fair price for that growth, leaving no margin of safety if the company even mildly disappoints. The current P/E is more than twice what the Graham & Dodd Matrix suggests it should be…

In my model, assuming an exit multiple of 31× 2030 earnings, which may be optimisitc still as it would suggest that FICO can grow EPS at similar rates for another 5 years from there, I get a fair value of $1,100 for the stock, and a target buy price, including a margin of safety, of about $940 per share, at which point I’d consider recommending the stock to Daniel as an addition to our Intrinsic Value Portfolio, assuming nothing major has changed for the worse with the thesis.

So, we’re passing on FICO for now, but what an incredible business it is to study. It’s worth your time to dive deeper into, as it’s the epitome of a wide-moat company, where its compounding is very unlikely to be disrupted by competitors for years to come. It’s a great example of a company I’d like to keep on my watch list to try and snap up shares of during a major market correction like we saw this past April.

But it’s possible to pay too much for quality, and in this case, I think the market is, even after this year’s correction in the stock, which is starting to not look like a correction anymore, after shares have leapt 20%+ in the last few days following this news:

Quick News Update

On Oct. 1st, Fair Isaac announced that it would change its pricing and distribution model for its mortgage scores. Fair Isaac will allow tri-merge resellers (specialized mortgage credit reporting agencies that pull all three bureau files on a borrower, merge them into one report, and return it to the lender) the option to directly calculate scores and bypass the credit bureaus. This sent FICO’s stock dramatically higher, rising 18%.

As we’ve discussed, Fair Isaac has encountered scrutiny over its price increases from lenders and government regulators, but it’s hard not to see this as FICO flexing its muscles, proving its pricing power and ability to potentially shift more of the scoring fee burden to consumers as opposed to lenders while cutting out the credit bureaus (Experian, TransUnion, and Equifax didn’t do well on the news.)

There’s speculation now that FICO may be able to double its revenue per mortgage(!)

This is a pretty material, and unexpected, change from when I first began researching the company, and I probably need more time to wrap my head around it, but generally speaking, the shares being 20% more expensive than they were two weeks ago doesn’t make Daniel or me more interested in the company.

If there are any experts on FICO in the audience, please write in and let us know if we missed anything!

More on our Intrinisc Value Portfolio, as well as recommended reading, watching, and listening, below. You can catch our full podcast on FICO here.

Weekly Update: The Intrinsic Value Portfolio

Notes

One of our watch list companies, Ferrari, which we covered six weeks ago, had quite the selloff this past week. The company debuted its new EV model, but wasn’t sufficiently optimistic on its forward earnings guidance, garnering some protest from Mr. Market. The stock was down about 20% for the week. Daniel and I love Ferrari’s business, but unfortunately, the valuation is still rich for us.

To begin getting excited about $RACE ( ▼ 0.29% ), we’d need another 20% correction or so. Maybe if we’re patient, Mr. Market will reward us, but we’re not buying the current dip. When relatively mature companies trade at nearly 50x earnings, as Ferrari did, their positioning becomes much more precarious, and selloffs like these are exactly what we intended to avoid by not paying an ultra-rich premium for a company that others might argue deserves the premium (just like with its cars).

If we see a price for Ferrari that starts to look attractive for us to add to our Intrinsic Value Portfolio, you’ll hear about it in our weekly updates here.

Quote of the Day

“If you can follow only one bit of data, follow the earnings — assuming the company in question has earnings…I subscribe to the crusty notion that sooner or later, earnings make or break an investment in equities. What the stock price does today, tomorrow, or next week is only a distraction.”

— Peter Lynch

What Else We’re Into

📺 WATCH: Where have all the entry-level jobs gone?

🎧 LISTEN: The Rise & Fall of Julian Robertson’s Tiger Fund

📖 READ: When Fed Chairs opine on stocks, should we listen? (Article from Aswath Damodaran)

You can also read our archive of past Intrinsic Value breakdowns, in case you’ve missed any, here — we’ve covered companies ranging from Alphabet to Airbnb, AutoZone, Nintendo, John Deere, Coupang, and more!

Your Thoughts

Do you agree with the portfolio decision for FICO?(Leave a comment to share your thoughts) |

See you next time!

Enjoy reading this newsletter? Forward it to a friend.

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here.

Join the waitlist for our Intrinsic Value Community of investors

Use the promo code STOCKS15 at checkout for 15% off our popular course “How To Get Started With Stocks.”

Read our full archive of Intrinsic Value Breakdowns here

Keep an eye on your inbox for our newsletters on Sundays. If you have any feedback for us, simply respond to this email or message [email protected].

What did you think of today's newsletter? |

All the best,

© The Investor's Podcast Network content is for educational purposes only. The calculators, videos, recommendations, and general investment ideas are not to be actioned with real money. Contact a professional and certified financial advisor before making any financial decisions. No one at The Investor's Podcast Network are professional money managers or financial advisors. The Investor’s Podcast Network and parent companies that own The Investor’s Podcast Network are not responsible for financial decisions made from using the materials provided in this email or on the website.