- The Intrinsic Value Newsletter

- Posts

- 🎙️ Mercado Libre: More than the Amazon of LATAM?!

🎙️ Mercado Libre: More than the Amazon of LATAM?!

[Just 5 minutes to read]

Half a year ago, we ventured into the Latin American market by investing in Nubank. That has served us quite well. So we thought, why not look at another Latin American poster child!

Mercado Libre has an incredible track record. In fact, it’s the only public company ever to grow by more than 30% year over year for 27 consecutive quarters…That’s almost 7 years.

It is often compared to Amazon since, ultimately, it’s an e-commerce giant. However, Mercado Libre has something that Amazon doesn’t have – Mercado Pago. Mercado Pago is a payments arm with operations and size similar to Nubank's.

So, technically, you get one of Nubank’s competitors plus an entire Amazon-like ecosystem. And you can buy all of this at the cheapest valuation Mercado Libre has ever traded at.

Let’s dive in!

— Daniel

Mercado Libre: E-Commerce + Payments = Unbeatable Flywheel

Every once in a while, there’s a statistic that sounds so absurd it almost feels made up. One of those “this can’t possibly be right” kind of numbers.

Such a statistic is the one I mentioned in the introduction. Mercado Libre has grown revenue by more than 30% year over year for 27 consecutive quarters.

And this is a company that had to fight many tough battles. Different currencies, different governments, inflation cycles, rate hikes, pandemics — you name it.

Now, the natural reaction to hearing that is: “Okay, so we’re obviously too late.” That’s usually how these things go. If something has already compounded like crazy, the opportunity must be gone, right?

Well, Mercado Libre continues to grow at these levels. And one of the reasons that’s possible comes down to e-commerce penetration in Latin America. That number is only around 14–15%. In the U.S., it’s closer to 25%. In the U.K., nearly 30%, and in China, it is well above that.

So, unless one believes that Latin America will permanently stop adopting online commerce at half the level of the rest of the world, which seems highly unlikely to me, there’s still a long runway ahead.

The valuation makes this all the more interesting. Despite this growth, despite the e-commerce underpenetration, and despite the fact that operating profit has gone from roughly $100 million to over $3 billion in just five years, the stock hasn’t exactly kept up.

Over that same period, Mercado Libre’s share price is up about 30% in total. To be fair, it wasn’t cheap before that, especially in 2021. So it has spent a couple of years growing into expectations that were a bit too optimistic at the time.

But today, the pendulum has swung in the other direction. Mercado Libre trades at its lowest valuation ever on an EV-to-EBIT basis, at roughly 30x operating earnings. On the surface, that doesn’t sound cheap. But for a company growing revenues around 30%, expanding profits, and still operating in massively underpenetrated markets, it’s at the very least worth a closer look.

Why Mercado Libre is More (and Less) than Amazon

At this point, it’s almost impossible to talk about Mercado Libre without someone calling it the “Amazon of Latin America.”

But that comparison does not tell the entire story. We’ve covered Amazon before, and one thing becomes very clear once you take a closer look: Amazon hasn’t really been “just” an e-commerce company for a long time.

The marketplace itself is huge, but the bulk of profits come from AWS. And then, of course, Amazon also happens to run an advertising business, a logistics empire, a subscription program, and, occasionally, launches rockets into space.

Mercado Libre doesn’t have an AWS equivalent, and it doesn’t shoot things into space. I can do without the space operations, but a cloud business would’ve been nice. However, the economics of both e-commerce operations can’t be compared one-to-one, either.

Mercado Libre never used its marketplace as a loss leader in the same way Amazon did. One reason for that is the product mix. Over 90% of Mercado Libre’s gross merchandise value comes from third-party sellers. That’s a very high-margin setup because Mercado Libre doesn’t own inventory, doesn’t take pricing risk, and doesn’t have to manage large balance sheets tied to physical goods. It earns fees for facilitating transactions and layering services on top.

Amazon, on the other hand, generates roughly half of its GMV from first-party products. That gives Amazon more control over pricing, quality, and the products it offers, but it also drags down margins.

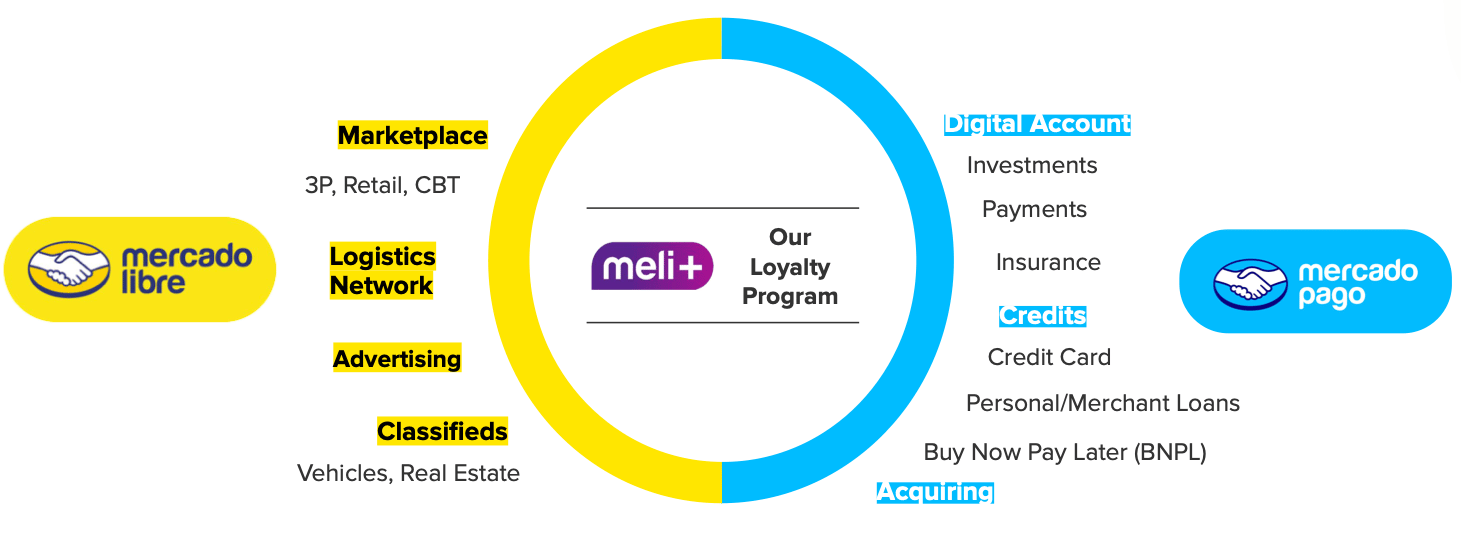

At a high level, Mercado Libre consists of three major pillars:

the core marketplace, a rapidly scaling logistics network, and a fintech business that has become one of its most important growth drivers.

A Brief History – The Second-Mover Advantage

If there’s one thing Mercado Libre’s history has made clear, it’s that a company can be successful without inventing new business models. Mercado Libre has won by copying what others did and perfecting it (Mohnish Pabrai calls this “shameless cloning”!).

Galperin came up with the idea for Mercado Libre while doing his MBA at Stanford, founding the company in 1999 alongside two co-founders. (He actually finished his degree, which sets him apart from many of the tech founders we’ve studied in this newsletter.)

Back in 1999, as you can imagine, every pitch deck boiled down to some version of “the eBay of X” or “the Amazon of Y.” Most of those ambitions didn’t age particularly well, though.

Mercado Libre Founder Marcos Galperin

Galperin’s original vision was actually closer to eBay than Amazon. In its early years, Mercado Libre focused on auctions rather than fixed-price listings. In some of the smaller markets where Mercado Libre operates, that legacy is still visible. When I visited the Dominican Republic last year, I realized that people use the platform almost like Craigslist.

In larger markets like Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina, though, the model shifted to fixed-price listings in the mid-2000s. Mercado Libre realized, also thanks to Amazon, that this is more likely to be the winning model.

But starting a LATAM e-commerce business was still much more difficult than doing so in the U.S. The biggest problems were low credit card penetration, unreliable deliveries due to insufficient infrastructure, and low trust between buyers and sellers.

Perhaps Mercado Libre's response to these challenges is why it was able to outcompete local and international competitors. Over and over again, management made the call to invest ahead of demand, absorb short-term pain, and fix bottlenecks that limited long-term scale.

Mercado Libre turned the challenges of subpar delivery and online payment infrastructure into a moat by building its own logistics network and payment company.

Building Infrastructure Where None Existed

Operating in Latin America is a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, it was almost impossible to build an AWS equivalent in LATAM when Amazon did so in the U.S. On the other hand, Amazon missed out on building a payments operation the size of Mercado Pago because such players already existed, and the necessity was not there.

But let’s start with Mercado Envíos, the company’s logistics network.

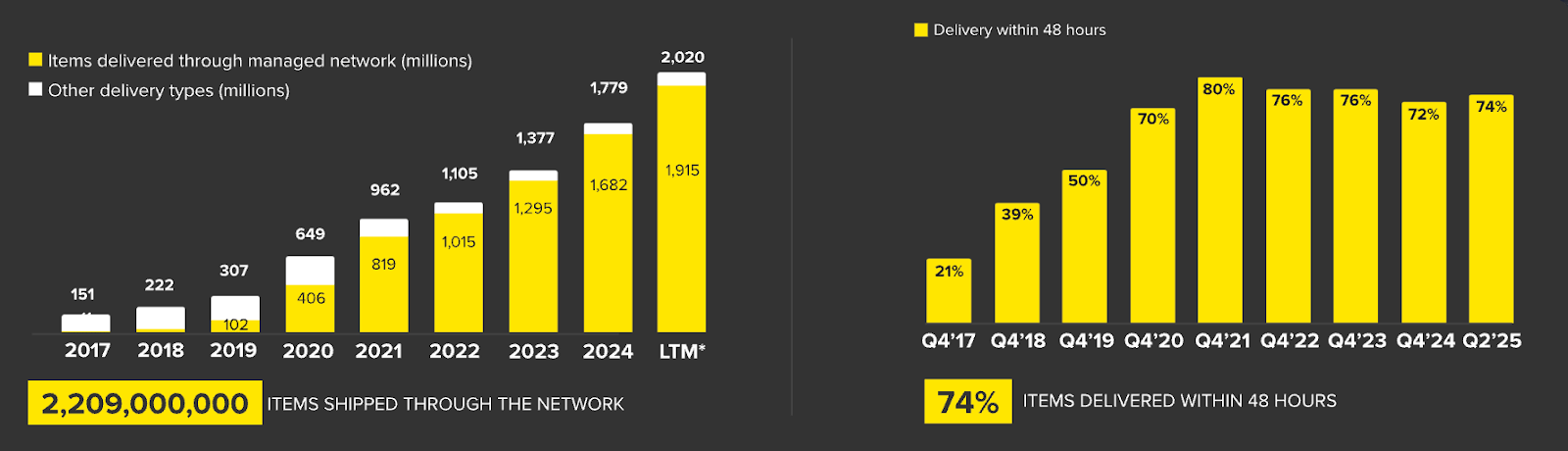

Launched in 2013, Envíos began as a fairly modest operation, primarily focused on standardizing shipping and negotiating better rates with third-party carriers. Sellers continued to hold inventory themselves, while Mercado Libre coordinated the process. That setup still exists today in what Mercado Libre calls the “Flex” model.

As volumes grew, Mercado Libre started building fulfillment centers where sellers could store inventory directly with Mercado Libre under the “Full” model. This is essentially what Amazon’s FBA is. And then there’s an in-between model called “Cross Docking,” where sellers deliver packages to Mercado Libre hubs, and Mercado Libre takes over sorting and transportation.

Over time, this evolved into a highly sophisticated network of warehouses, sortation hubs, pickup and drop-off points, and even air transport, with Mercado Libre now operating its own fleet under the Meli Air brand.

Today, 94% of packages are delivered through Mercado Libre’s own logistics network, and about three-quarters arrive within 48 hours. That is very, very good, even by U.S. or European standards. My Amazon packages never arrive within a day either. Although I’m a Prime user!

But there are differences compared to Amazon’s logistics network. Unlike Amazon, which tends to own large parts of its logistics stack outright, Mercado Libre took a more hybrid approach. Many facilities are leased rather than owned. And a large portion of the last-mile delivery still runs through local partners rather than fully in-house fleets.

At first, that might seem like less of a moat, but it does make a lot of sense when you think about the risks in Latin American markets. You don’t want to own billions in hard infrastructure in markets where political and economic conditions can shift quickly. You want to be flexible, scale up, pull back, or reroute capacity without being stuck with stranded, and therefore worthless, assets.

And since Mercado Libre is the biggest and sometimes only customer for the local last-mile delivery companies, they still have meaningful operational control.

As we know from Amazon, building a logistics network is expensive. New warehouses take time (and volume) to reach optimal utilization, free shipping subsidies (to increase volume) compress margins, and delivery speed improvements take even longer to show up positively in the results.

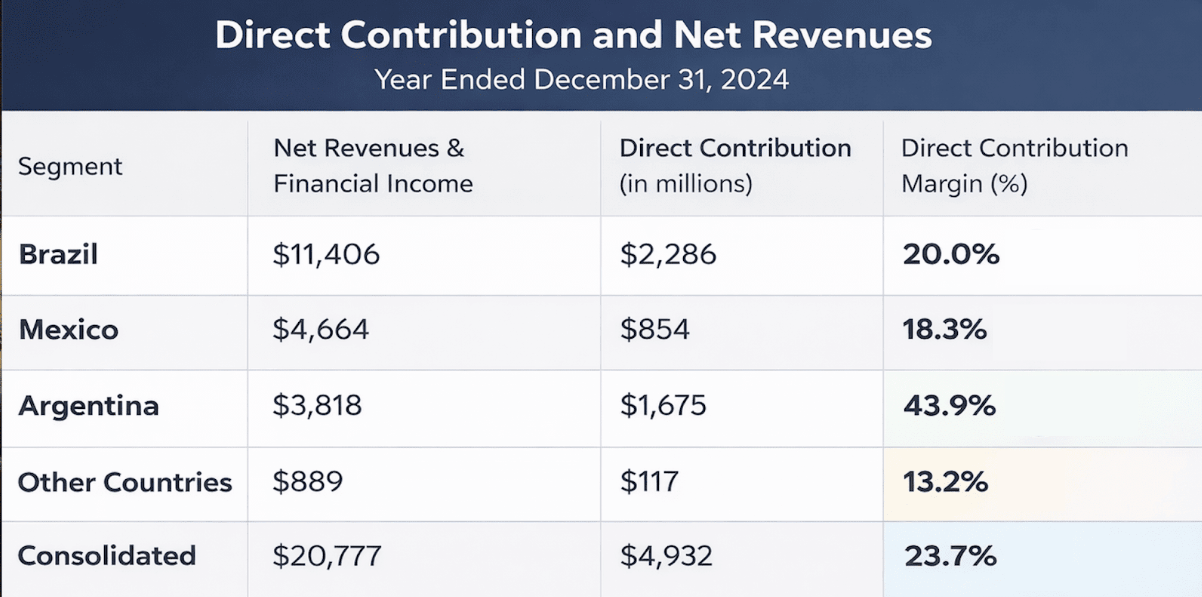

Markets like Brazil and Mexico are still in heavy build-out mode. Argentina, where much of the logistics infrastructure is already in place, shows what happens on the other side of that investment curve: lower incremental capex and meaningfully higher contribution margins.

FYI: Contribution Margin is the sales revenue left after subtracting variable costs (materials, direct labor), showing how much each unit sold contributes to covering fixed costs (rent, capital expenditures) and generating profit, calculated as Sales Revenue - Variable Costs.

But it’s not only the physical logistics infrastructure. Argentina is also special as it’s the most mature payments market for Mercado Libre. And that’s even better scalable. Once the payments and credit infrastructure are in place, the marginal cost of generating an additional peso of fintech revenue is much lower. There’s very little physical infrastructure involved, and most costs don’t scale linearly with volume.

And that brings us to Mercado Pago…

Mercado Libre’s Ace in the Hole

As I said, to some extent, Mercado Libre was forced into Pago for its own good. The payment infrastructure for an e-commerce giant wasn’t there, so it had to be built from scratch.

What started as a basic payment tool on the marketplace gradually evolved into Mercado Pago — a fintech platform that now processes massive transaction volumes both on and off Mercado Libre.

In fact, today, Mercado Pago processes more payments outside the Mercado Libre marketplace than on it. As such, beyond being just a feature for Mercado Libre customers, it has become a strong flywheel in its own right.

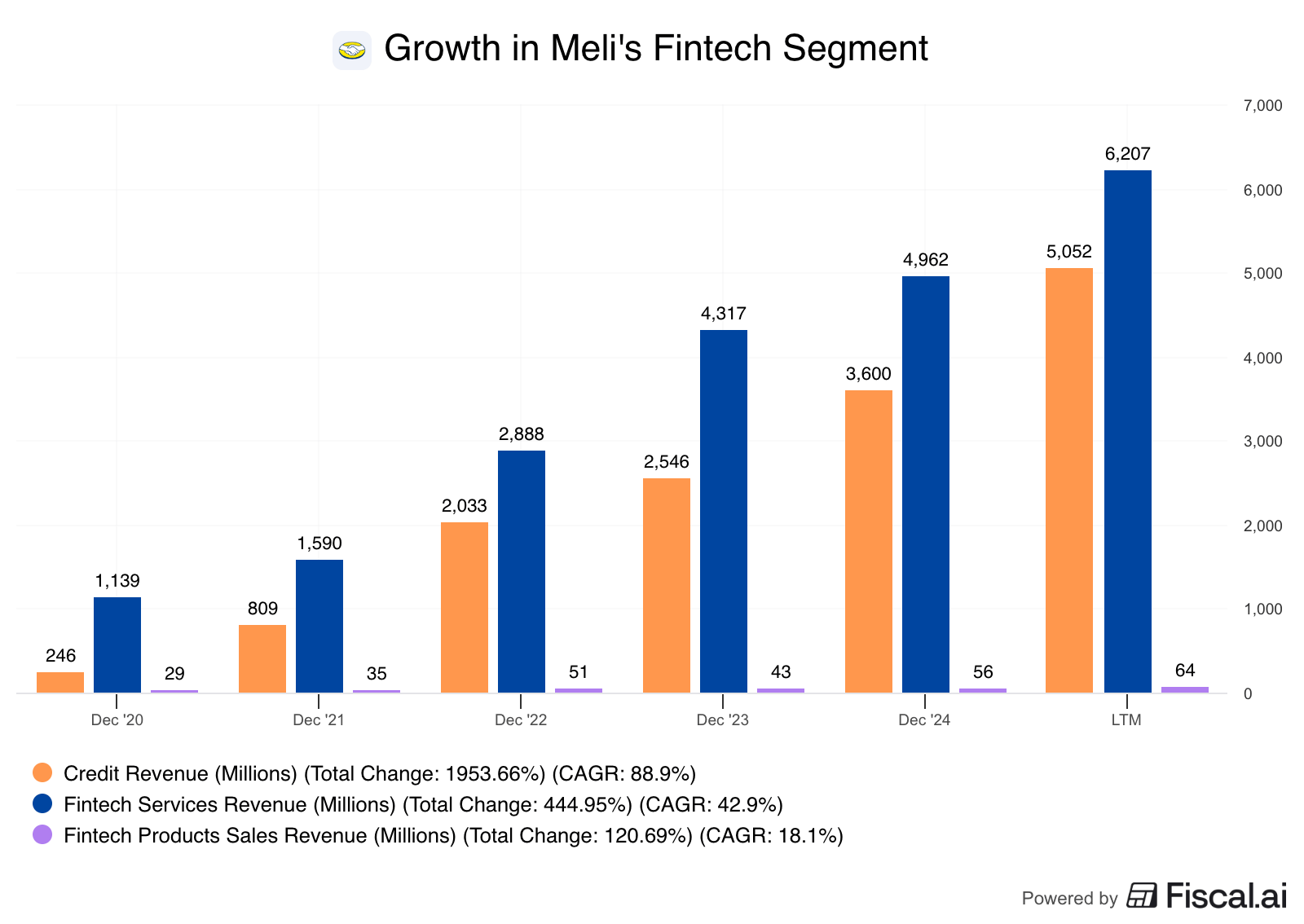

At a high level, Mercado Pago monetizes itself in three ways.

First, payments. Merchants use Mercado Pago as an online checkout solution and via QR codes and point-of-sale devices offline. Mercado Libre then earns a small fee on every transaction.

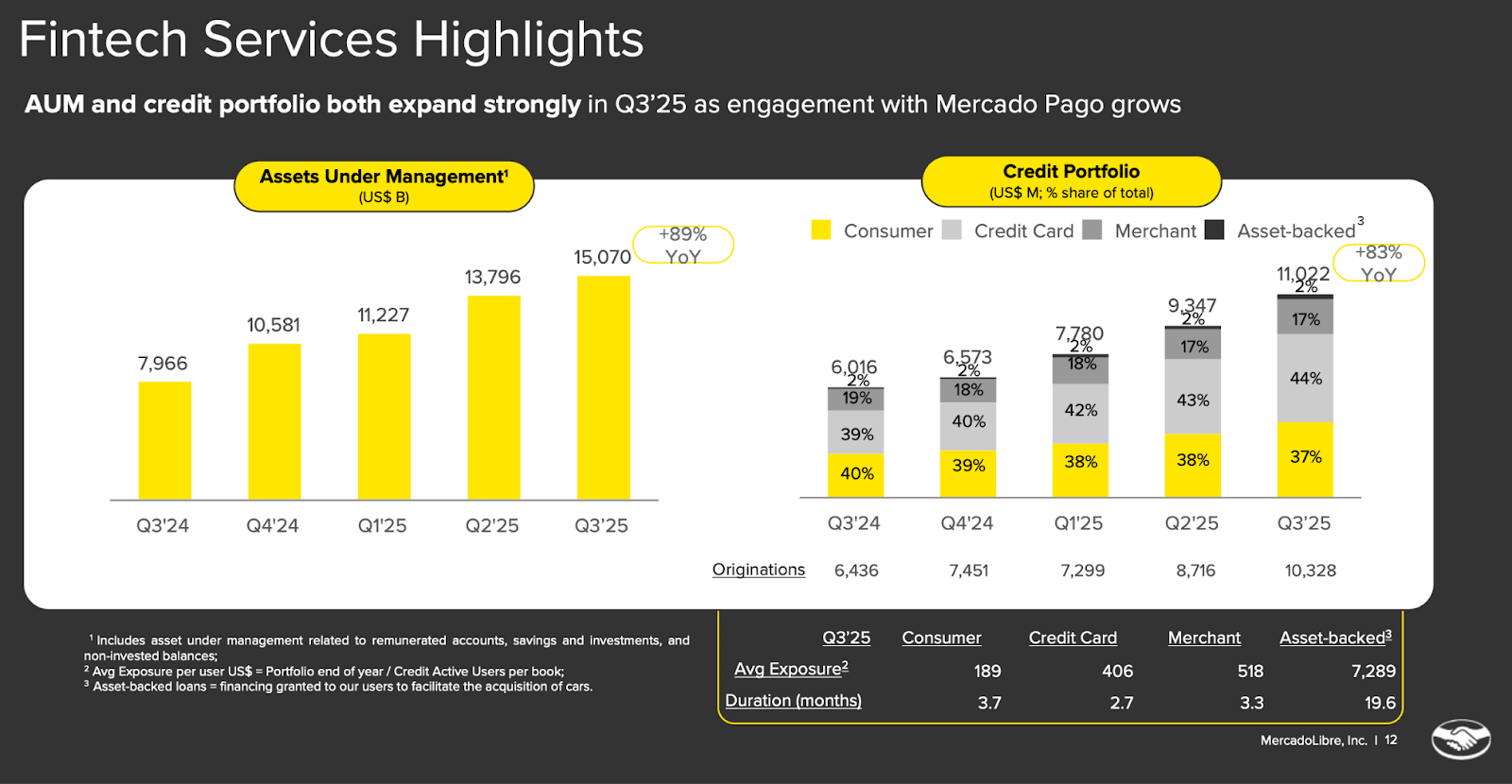

Second would be credit. Mercado Pago offers credit cards, consumer loans, and working-capital advances to merchants. This has become the fastest-growing part of the fintech business by far, with the credit portfolio compounding at extremely high rates over the last several years.

And third, financial services. That includes point-of-sale hardware sold to offline merchants, as well as asset-management products that allow users to earn yield, hold stablecoins, or otherwise keep money inside the Mercado Pago ecosystem.

These products account for a very small share of Fintech revenue, but they’re strategically important because they bring offline merchants into the Mercado Libre/Pago ecosystem.

The big advantage of pairing e-commerce with payments is cheaper customer acquisition and a reinforcing flywheel between Mercado Libre and Mercado Pago users. Every checkout is an opportunity to onboard a new Pago user. And with the trust already built through Mercado Libre, conversion is pretty good. And from there, it’s only a small step to use it off-marketplace as well.

When you think back to our Nubank pitch, low customer acquisition costs, very little physical infrastructure, and well-run algorithms have been key to its success. Personally, Mercado Pago is even more intuitive to me. Mercado Libre can collect so many data points about its customers, and its algorithms can be trained on the best data available, on both sides of the transactions, consumers and merchants.

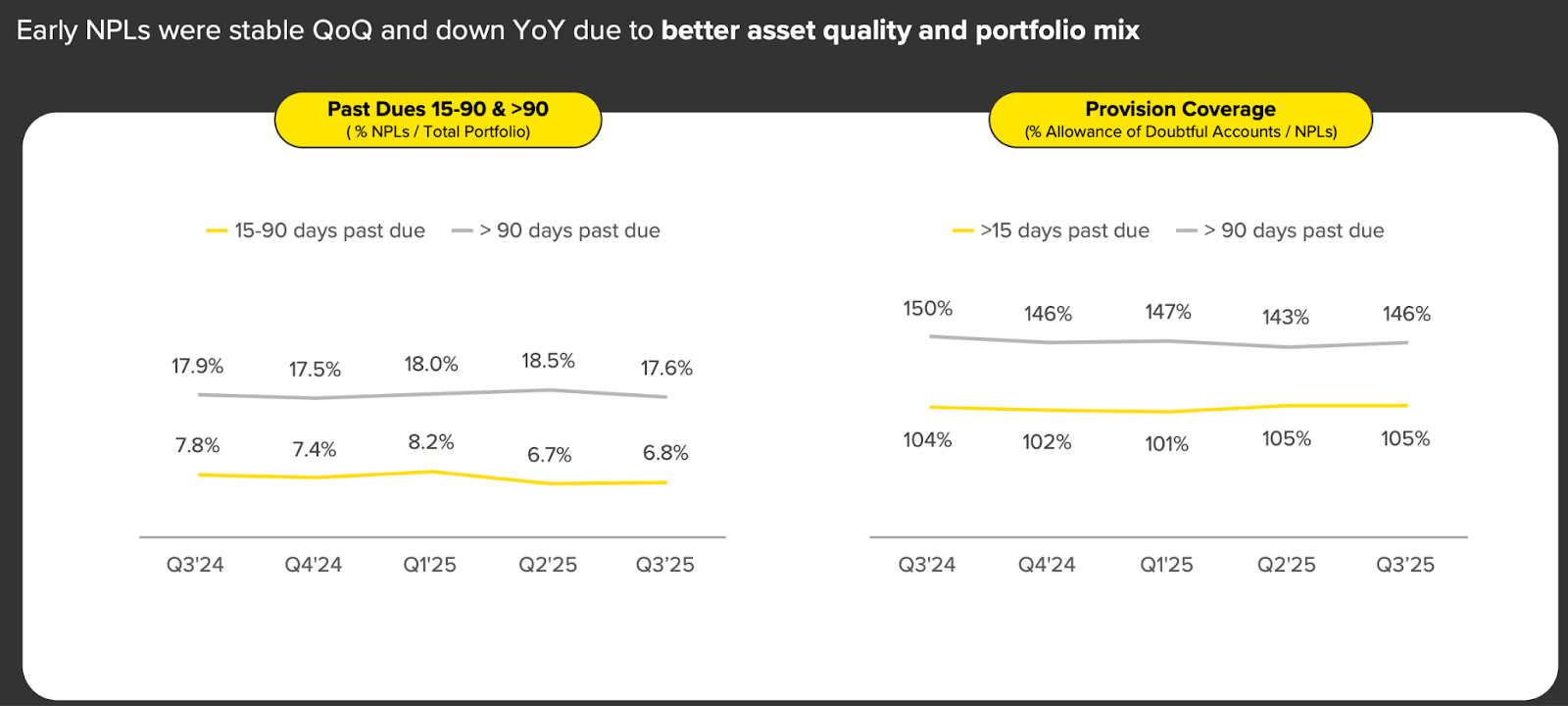

Perhaps that’s why Mercado Pago is also confident in underwriting riskier loans. The most important metrics to check the risk and health of a credit underwriting portfolio are so-called NPLs – non-performing loans.

The two points in the loan timeline you usually check are loans that go delinquent after 15 days and after 90 days.

Nubank’s NPLs are noticeably lower than Mercado Pago’s. That simply means a smaller share of its borrowers end up missing payments. 15-day NPLs sit at 4%, and the 90-day bucket is about 7%. Mercado Pago’s NPL rate after 15 days is 7%, and after 90 days, it rises to 17.5%.

One is not necessarily better than the other. Ultimately, it’s about the risk-adjusted margin that you earn and your ability to shoulder losses when an economic downturn comes. In Mercado Pago’s case, that margin is 20%, compared to slightly less than 10% for Nubank.

So, in other words, Mercado Pago takes on more risk, but it also gets paid significantly more for doing so. And importantly, both of them carry more reserves (provision coverage) than needed to cover all expected losses.

Nevertheless, a major downturn in one of Mercado Pago’s key markets would test this strategy, so you’re trusting management to price and manage the risk correctly. That’s true for Nubank as well, though.

Competition – Amazon, Shopee, and Co.

For years, investors have feared Amazon would enter Mercado Libre’s markets and take share. Amazon is active in the region and has expanded fulfillment capacity, but it hasn’t meaningfully increased market share in key markets like Brazil for quite some time now.

Amazon’s logistics network isn’t as denseas Mercado Libre’s, and it doesn’t have an integrated fintech arm like Mercado Pago. And, frankly, I suspect Amazon’s priorities lie elsewhere.

To truly compete, Amazon would have to spend a lot of time and money against an established, well-run incumbent, and it may simply not be worth it. I joked earlier that Amazon now shoots rockets into space, but there is a point to that. Everything has an opportunity cost. Maybe being a smaller player in Latin American e-commerce is Amazon’s trade-off.

Then there are the Asian competitors, and the one that comes up most often is Shopee. Shopee entered Brazil in 2019 and has since become the clear number-two player, with roughly 17% market share. Mercado Libre is still far ahead at around 35%, though.

Outside Brazil, Shopee has largely shifted toward cross-border shipping, meaning products are shipped from abroad rather than fulfilled locally. That helps keep prices very low, but you lose control over speed and reliability. Same-day or next-day delivery simply isn’t possible at scale without local fulfillment.

Even in Brazil, Mercado Libre has roughly twice the logistics footprint that Shopee does. That includes warehouses, sortation hubs, pickup points, and last-mile partnerships, which lead to faster delivery, fewer failed shipments, and easier returns.

So yes, Shopee can absolutely win in categories where price is the only thing that matters. But for most repeat purchases, speed and trust matter too, and that’s when Mercado Libre’s logistics network starts to make a difference.

Last but not least, there’s Temu. As Shawn mentioned in our podcast, the hype around Temu has seemed to cool down a bit after they burst onto the scene with huge marketing campaigns. There was a time when you couldn’t scroll social media without getting flooded by Temu hauls.

But Temu has no logistics network in any Latin American market, including Brazil. Thus, I can’t imagine them gaining (and sustaining!) market share in the long run. The average wait time for their packages in Brazil is 2-3 weeks. That’s a whole lot considering the clothes themselves don’t survive much longer.

Beyond comparing the value proposition itself, another factor matters as well. Stig Brodersen, the co-founder and CEO of The Investors Podcast, likes to remind us that capitalism is brutal, and correspondingly, it’s not always the best product that wins.

Governments generally have an incentive to support local ecosystems. Mercado Libre is much more than a platform for selling goods — increasingly, it’s a marketplace where millions of local small and medium-sized businesses earn their income. When ultra-cheap cross-border imports flood the market, they don’t just hurt competitors; they hurt small local businesses and, by extension, consumers.

Some measures by Latin American governments have already been introduced to counteract this. Mexico, for example, introduced a 19% VAT on low-value imports from countries without a free trade agreement, explicitly targeting the kind of shipments that platforms like Temu and Shein rely on.

Ultimately, I believe that Shopee is here to stay. That said, I think a market of Latin America's size and growth has enough room for two successful players. And if that turns out to be mistaken, I’d bet my money on Mercado Libre still.

The Rest of the Ecosystem – Ads, Meli+ and CO.

I think it’s already clear how Mercado Libre uses each part of its business to create a powerful flywheel. But, like every good ecosystem, there is still room for improvement. Again, Mercado Libre does not really have to reinvent the wheel. One of Amazon’s most successful business units is ads. So, surprise surprise, Mercado Libre is currently building its own ads business.

One of the most valuable things a marketplace owns is the moment of purchase. There are very few situations where users are more willing to spend money than when they are actively searching for a product they already intend to buy. That makes marketplaces some of the best ad real estate imaginable.

Mercado Libre’s ads business is still in its early innings. It accounts for only 2% of GMV, but it is growing rapidly and already represents half of all digital retail ad spending in Latin America.

Of course, the overall digital ad market is much bigger. Mercado Libre’s share is about 3.7%. So there’s plenty of room to grow, and as we’ve come to appreciate from studying companies like Amazon, Alphabet, Roku, and Reddit, ad businesses are among the most compelling opportunities for large, established marketplaces.

Mercado Libre has also started expanding into off-site advertising, meaning it can now use its marketplace data to target users on platforms like Google or Disney+.

Another lesson from the Amazon playbook is Meli+, Mercado Libre’s answer to Amazon Prime. Customers pay a monthly or annual fee and receive benefits like free or discounted shipping, faster delivery, and bundled digital services such as streaming content.

Just like Prime in its early years, it’s run close to breakeven or even at a loss on a standalone basis. But Meli+ users are more engaged. They buy more frequently, spend more per user, and are far more likely to use Mercado Pago — both online and offline. In other words, Meli+ increases lifetime value across the entire ecosystem.

There’s also a subtle but important interaction with logistics here. Higher purchase frequency increases delivery density. Higher density lowers per-unit shipping costs, and lower costs allow Mercado Libre to improve service levels or reduce subsidies over time. That, in turn, makes the loyalty program more attractive. And around the flywheel it goes.

We are running long today, but before we go to the valuation and decide on whether we add Mercado Libre to The Intrinsic Value Portfolio, let’s take a brief look at the management team.

Management – Capital Allocation and Doing Boring Things Right

Mercado Libre has been founder-led for more than two decades. Marcos Galperin ran the company with a strong long-term bias and a clear understanding of what it takes to operate in Latin America.

He’s also not a promotional CEO. He doesn’t attend earnings calls anymore, and he has repeatedly been willing to sacrifice short-term margins to strengthen the long-term position, whether that meant building logistics ahead of demand, subsidizing shipping to accelerate adoption, or scaling fintech early.

It’s easy to say you’re long-term focused, but it’s much harder to keep doing it when the next quarter looks worse. Shawn and I have heard the words “long-term focused” a dozen times now, but then you listen to the earnings call, and that long-term focus is nowhere to be seen.

Galperin stepped down as CEO at the end of 2025, but I wouldn’t expect any dramatic changes. The new CEO, Ariel Szarfsztejn, was handpicked internally and has been with the company since 2017. Galperin remains Executive Chairman and a large shareholder, owning about 7% of shares, keeping incentives aligned.

Capital allocation has been unusually disciplined, too. Share-based compensation is minimal, well below 1% of revenue, so growth hasn’t come through dilution. And reinvested capital has earned very high returns, with ROIIC around 35% over time.

Alright, let’s talk valuation and see whether the numbers match the narrative.

Valuation and Investment Decision

Sometimes you go into a valuation exercise with a pretty good sense of what the model will tell you. That’s usually the case with slower-growing, cheaper businesses, where modest assumptions already get you most of the way there.

With a company like Mercado Libre, that intuition is much less reliable.

When a business is still growing close to 30% and trades at multiples around 30x, a standard five-year cash flow model can easily swing from “clearly expensive” to “surprisingly attractive” depending on a handful of assumptions. Going into the analysis, it genuinely wasn’t obvious to me at all whether Mercado Libre would even look cheap, despite it currently trading at its cheapest EV-to-EBIT multiple ever.

So let’s start with a base case.

For revenue growth, the assumption is a gradual slowdown from today’s roughly 30% pace to the low-20% range over the next five years. Mid-20s growth in the near term, fading into the mid-teens as the business scales.

On margins, I assume slight pressure over the next couple of years, followed by a recovery starting around 2027. This reflects continued logistics investment in Brazil and Mexico, as well as competitive intensity in the commerce part of the business.

Over time, as those investments mature and higher-margin businesses like ads and fintech gain more weight, operating and net margins recover and reach multi-year highs by 2030.

Using these assumptions, keeping the share count unchanged, applying a 26x multiple and a 10% discount rate, deliberately higher than the usual 8% to account we use, for geographic and macro risk, the resulting fair value comes out around $2,700 to $2,800 per share. Applying an additional 20% margin of safety brings that down to roughly $2,200.

When we recorded the episode, before the Venezuela incident, Mercado Libre was trading close to $1,900. At that price, the model implied an expected annual return of about 17%. Today, the stock trades much closer to our intrinsic value estimate, which lowers the expected return to around 15%. Still respectable, though.

In the Notes section below, I have added a comment explaining our policy on when we add positions. For now, let’s continue with the Bull and Bear case.

So, if one is more optimistic, say revenue growth stays closer to 25%, and operating margins reach 20% by 2030, fair value moves into the $3,000+ range. Apply a higher multiple, closer to 30x, and upside scenarios start pushing toward $3,500. This is not a prediction, by the way. It’s more of a sensitivity exercise showing how strongly valuation responds to margins and multiples.

The same logic applies on the downside.

A serious macroeconomic downturn in one of Mercado Libre’s core markets could hit both sides of the business at once. Credit growth would slow sharply, losses would rise, and a large portion of the capital invested in scaling fintech and logistics would take much longer to earn an adequate return.

If growth slows to the low double digits and margins stagnate, a lower multiple, around 20x, would be reasonable. In that scenario, you can justify a stock price closer to $700. Likely? Definitely not. Possible? Sure.

When these scenarios are probability-weighted at today’s prices, the expected return comes out around 14–15%, comfortably above our 12% hurdle rate, but with materially higher possible volatility than a typical developed-market compounder.

Considering this and given that we already hold 4% of the portfolio in Nubank, another emerging-market investment operating in a similar industry, we decided to initiate a 3% position in Mercado Libre.

Over time, we will likely consider position sizing for Nubank and Mercado Libre together, especially if combined exposure approaches 10% of the portfolio. Just a week and a half ago, that cap felt conservative to me. As a European, I’m used to greater exposure to emerging markets.

After recent events, however, keeping a tighter lid on emerging-market exposure doesn’t seem unreasonable.

For more on Mercado Libre, you can listen to our podcast here.

More updates on our Intrinsic Value Portfolio below 👇

Weekly Update: The Intrinsic Value Portfolio

Notes

We often get questions about the timing of when positions are added to the portfolio, so I thought I'd quickly clear that up here:

Positions are added to the portfolio right after the episode is recorded, not when it is released. That’s also the point in time when positions are initiated in our personal portfolios.

Because of that, there can be a gap of a few weeks (at most) between the price discussed during the episode and the price readers see when the newsletter goes live. Markets move, news happens, and prices can change in the meantime. In the Newsletter, we can react to this; in the episodes, we can’t.

We also intentionally record episodes with some leeway before release. That buffer allows us to publish on a reliable weekly schedule, without exceptions, rather than rushing analysis or running the risk of not uploading in time.

The trade-off is that prices may look slightly different by the time the episode is released, but the investment framework and long-term thesis remain unchanged. And in the newsletter, you’re always up to date anyway.

Quote of the Day

"The longer you extend your time horizon, the less competitive the game becomes.”

— Howard Marks

What Else We’re Into

📺 WATCH: Venture Capital Investing Legend Bill Gurley on AI, China, and Life Lessons on the Tim Ferriss Show

🎧 LISTEN: Clay Finck discusses the book Hidden Investment Treasures by Daniel Gladiš

📖 READ: Bloomberg’s List of Stocks to Watch for 2026

You can also read our archive of past Intrinsic Value breakdowns, in case you’ve missed any, here — we’ve covered companies ranging from Alphabet to Airbnb, AutoZone, Nintendo, John Deere, Coupang, and more!

Do you agree with the investment decision on Mercado Libre?Write a comment to elaborate |

See you next time!

Enjoy reading this newsletter? Forward it to a friend.

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here.

Join the waitlist for our Intrinsic Value Community of investors

Shawn & Daniel use Fiscal.ai for every company they research — use their referral link to get started with a 15% discount!

Use the promo code STOCKS15 at checkout for 15% off our popular course “How To Get Started With Stocks.”

Follow us on Twitter.

Read our full archive of Intrinsic Value Breakdowns here

Keep an eye on your inbox for our newsletters on Sundays. If you have any feedback for us, simply respond to this email or message [email protected].

What did you think of today's newsletter? |

All the best,

© The Investor's Podcast Network content is for educational purposes only. The calculators, videos, recommendations, and general investment ideas are not to be actioned with real money. Contact a professional and certified financial advisor before making any financial decisions. No one at The Investor's Podcast Network are professional money managers or financial advisors. The Investor’s Podcast Network and parent companies that own The Investor’s Podcast Network are not responsible for financial decisions made from using the materials provided in this email or on the website.