- The Intrinsic Value Newsletter

- Posts

- 🎙️ Lululemon: Still the King of Athleisure?

🎙️ Lululemon: Still the King of Athleisure?

[Just 5 minutes to read]

If I told you about a company that grew its sales by over 22% a year over the past five years, achieved gross margins of 59%, boasted industry-leading operating margins, and maintained a remarkable 5-year average return on invested capital (ROIC) of 35%, all while consistently shrinking its share count, you’d probably expect the company to be trading at, what, 35x earnings, maybe 25-30x earnings, depending on the industry?

Well, to buy shares in North America’s most iconic athleisure brand, with the characteristics described above, you might be surprised to learn that the stock trades at less than 13x the earnings the company is expected to generate over the next 12 months…

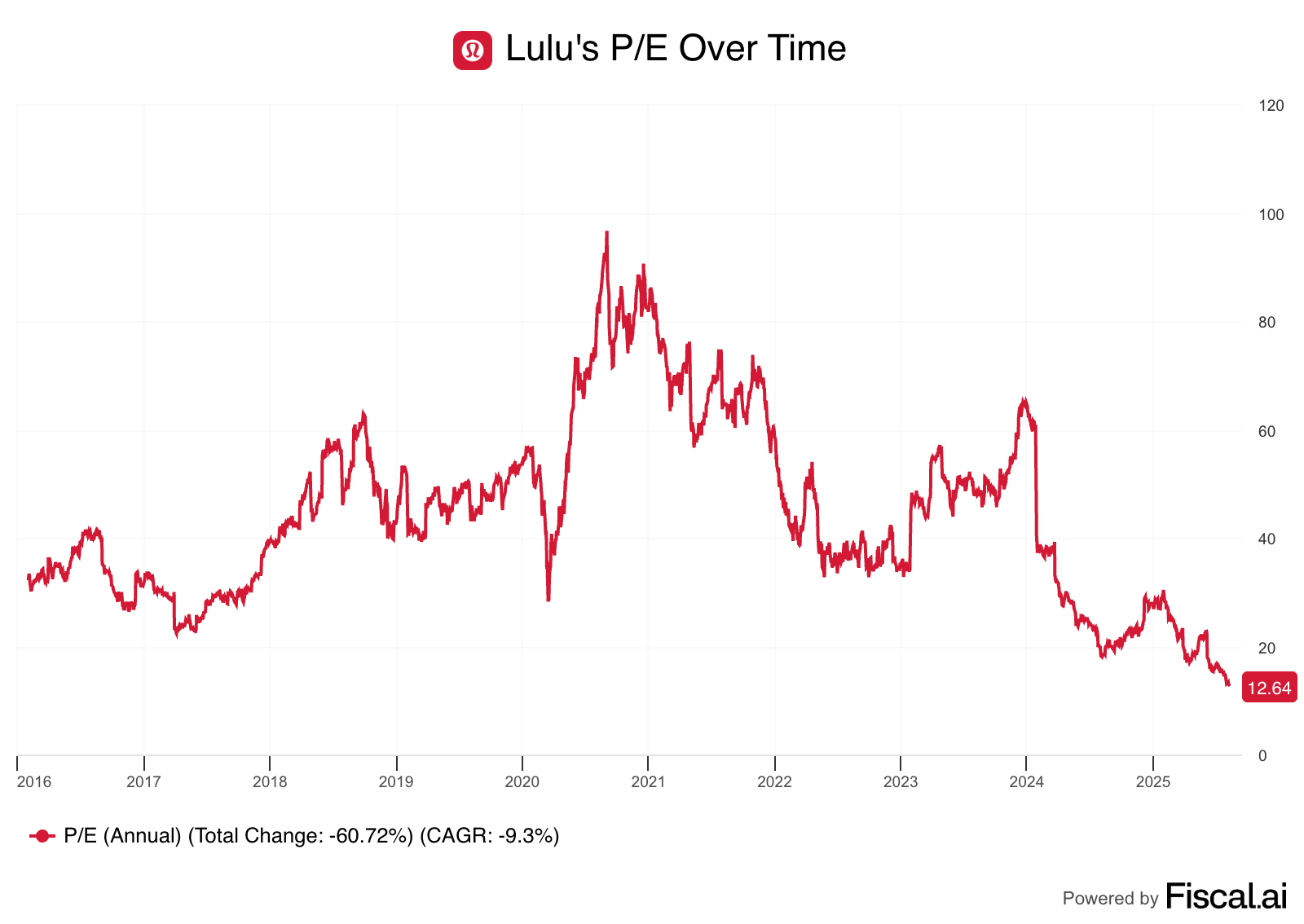

Despite its incredible fundamentals, Lulu’s stock is depressed, trading down sharply from a valuation of 65x earnings just 18 months ago(!) Consider us intrigued.

Let’s discuss.

— Shawn

Want to go to Montana with Daniel and Shawn?

The Investors Podcast Network is hosting our Summit Event in the mountains of Big Sky, Montana!

Attendees will have the opportunity to meet like-minded value investors and enjoy delicious food in a wonderful setting. We have no doubt that this will make for an unforgettable experience that Shawn, Daniel, and Clay Finck of We Study Billionaires can’t wait to share with you.

Rather than hosting yet another conference in a room full of suits, we decided that there was no better place to meet kindred spirits than in the serenity of the mountains, away from all of the noise.

Sounds fun, right? You can apply to join below (spots are limited).

P.S. Members of our Intrinsic Value Community get a special discount to attend.

Lululemon: Stretched Valuation No More

Lululemon store

Twenty-seven years ago, Chip Wilson asked a simple question: Why were yoga practitioners forced to choose between comfort and modesty? The answer emerged in Lululemon’s now signature flat-seamed, nylon-heavy leggings that banished chafing. The product solved a genuine problem, but it also struck a cultural nerve.

Suddenly, workout gear could accompany its owner from studio to coffee shop to grocery aisle, without embarrassment. Thus, the concept of “athleisure” was born out of Vancouver, Canada, and so was a winning stock.

The formula—technical fabric, flattering cut, premium price, scarcity via tight distribution—scaled faster than even Wilson expected. The first U.S. store opened in 2003, and its inventory sold out between deliveries.

As Daniel likes to tell me, the best premium/luxury brands are born out of functionally dominating a given niche (like Moncler), and well, here’s Lululemon upholding that same pattern, growing from yoga wear dominance to all types of wear.

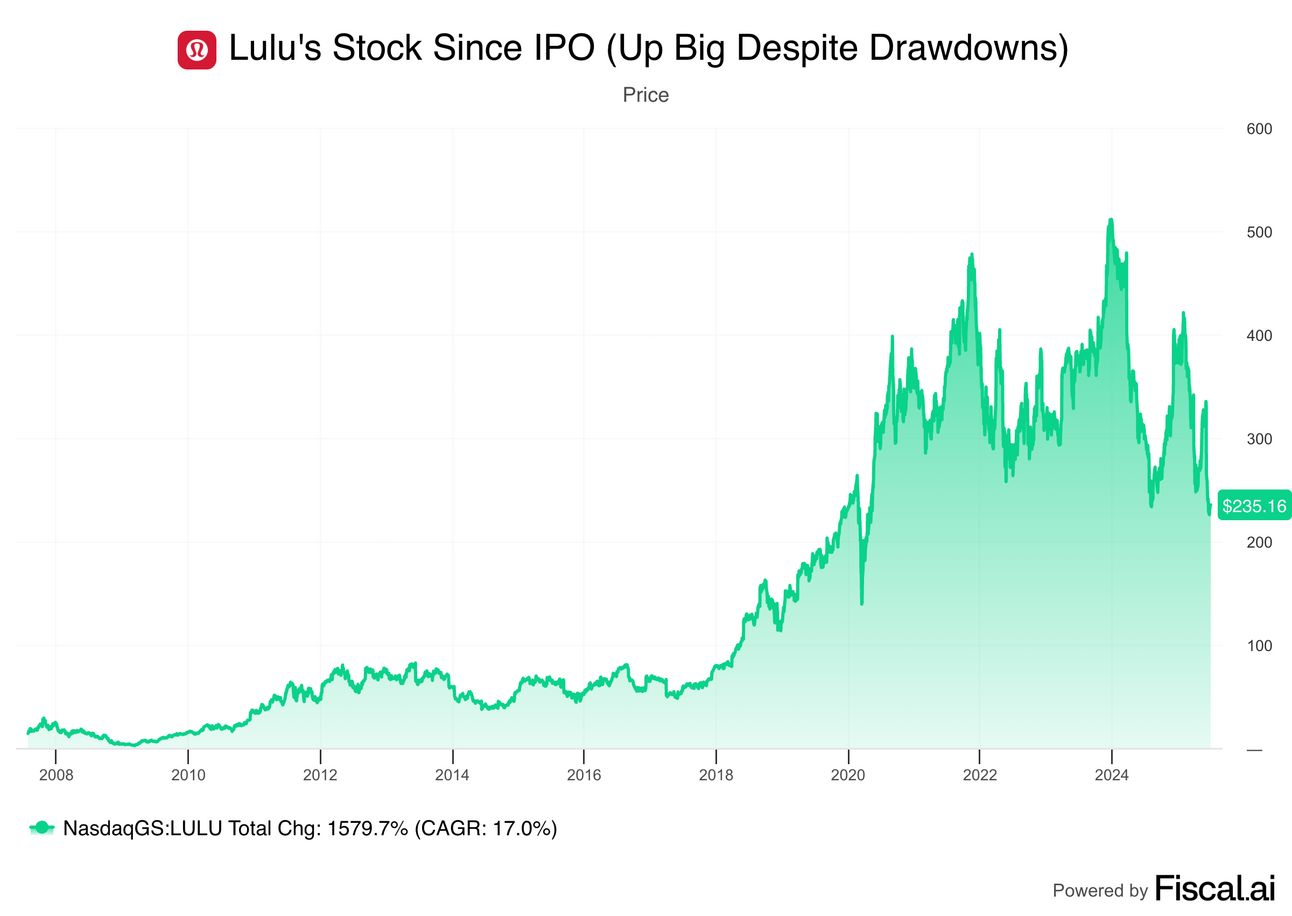

By the time the company rang the IPO bell in 2007, the logo itself functioned as a shorthand for wellness and disposable income. From that listing ‘til now, the stock has compounded at 17% a year. Loyalists treated new Lulu drops as calendar events, and the brand’s retail footprint swelled to more than 760 locations across two dozen countries. Its digital business followed the same arc, with E-commerce quickly ballooning during the Pandemic to now account for about half of total sales.

None of that expansion diluted profitability, though.

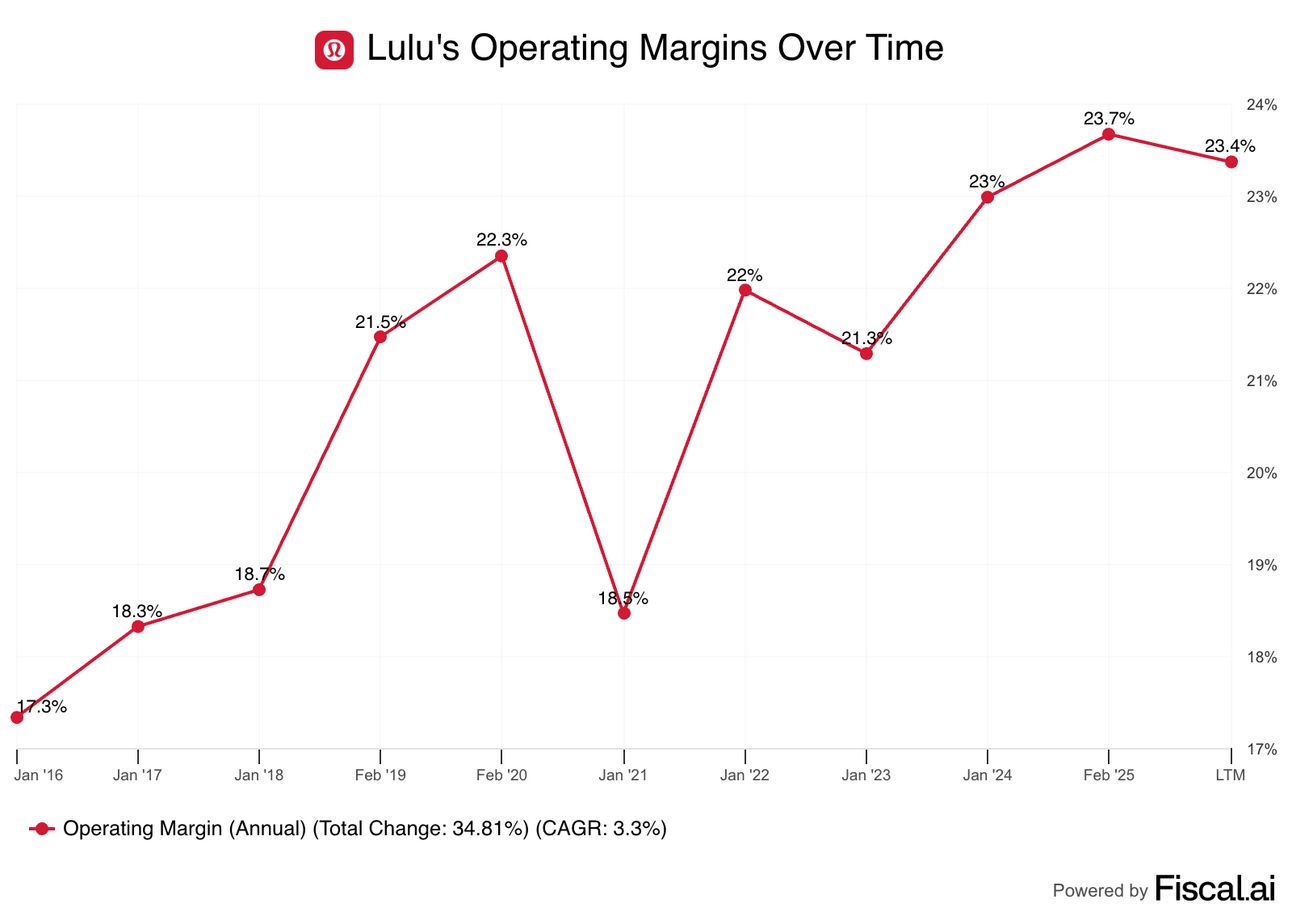

A best-in-class gross margin has persisted in the high-fifties, and operating margins remain about double Nike’s and have been steadily rising, as the company has repeatedly doubled its sales overall (growing its menswear and international sales even faster).

Consistent Operating Margin Growth, Minus Covid-Era Blips

Cash flows have been robust enough for management to repurchase more than $3 billion of stock from 2017 onward. For investors who love businesses that self-fund growth, self-disrupt, and self-shrink the share count, I present Lulu.

While the flywheel has wobbled, causing Mr. Market to panic and send this great franchise from a premium multiple of 65x earnings to, well, where it trades today, I think the multiple now reflects excess pessimism and concern.

NTM and TTM P/E is ~13x

The question is whether that multiple crash is justified, but before we get too far ahead of ourselves, let’s take a step back and ask:

How Can a Brand Charge Triple-Digits for Leggings?

To answer this question, I’d argue that Lulu has genuine product differentiation. Lulu’s fabrics—Luon, Nulu, Everlux—contain greater quantities of nylon micro-fibres than the industry’s typical polyester blends. They breathe, wick moisture, resist pilling, retain shape, and survive the wash-and-wear torture test (I’m sure many readers or their spouses can attest to this). Many women who owned cheaper tights and upgraded to Lulu’s Aligns discovered they no longer needed to buy replacements twice a year.

Word of mouth promotion exploded the brand’s debut.

Yet raw fabric science explains only a slice of Lulu’s pricing power. Scarcity and symbolism matter at least as much. Lulu avoids department-store aisles and keeps wholesale partnerships below 10% of revenue (contrast that with our discussion of Nike previously.)

In other words, if a customer wants to wear Lulu’s signature “stylized A” logo, they must visit one of its branded boutique stores or order from the website. You won’t find them at Dick’s Sporting Goods or Target.

That deliberate restriction signals exclusivity and preserves full-price sell-through rates that most retailers can only envy. Every brand would love to control its own distribution, yet few possess the brand power to pull in enough customers to support a retail footprint entirely of their own products, driving them to sell wholesale through diversified retailers, which ultimately forces brands to compete for shelf space (often by discounting, eroding the brand’s value over time).

So relying less on wholesales also lets management decide precisely when, where, and how often a markdown appears, which occurs hardly ever at Lulu, outside of its semi-annual clear-outs on Black Friday and Boxing Day (the day after Christmas).

As I mentioned, traditional advertising has never powered the growth engine here over word of mouth. While competitors like Nike and Adidas pour 8-13% of revenue into marketing, Lulu spends roughly half that proportion. The company farms a different field, relying on small-scale influencers, aka “ambassadors.” These are often local yoga teachers and run club leaders, who are rewarded for wearing the brand frequently.

An instructor who teaches four classes a day, six days a week, becomes a moving billboard and a far more personalized advertising touchpoint than any Facebook or Google ad. Studio classes inside Lulu stores pull foot traffic and take a hands-on approach to building the company’s branding/culture, without the cost of splashy campaigns.

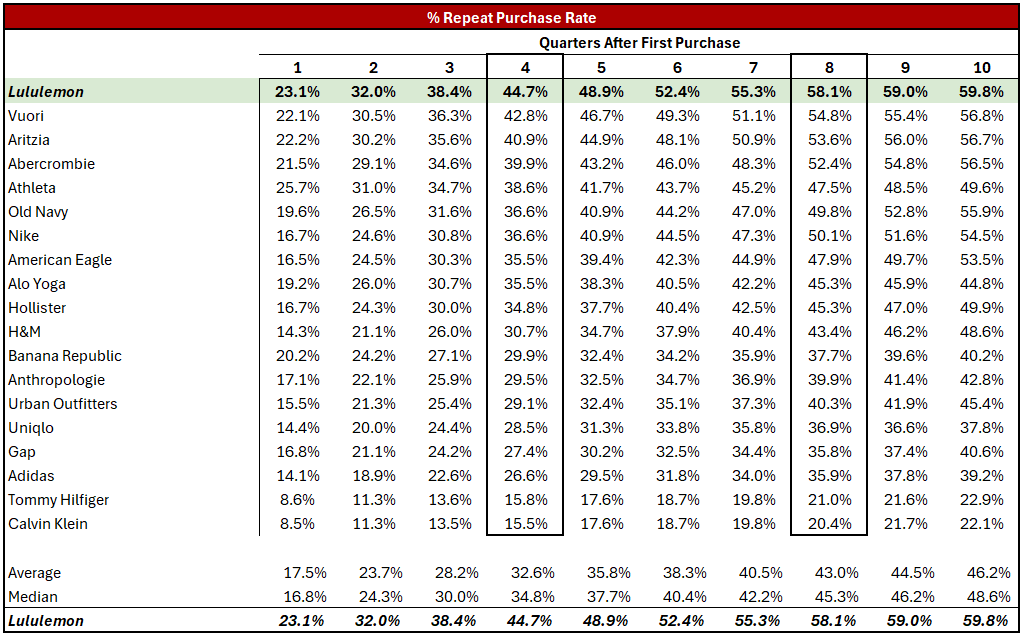

With this strategy has come impressive loyalty. Nearly 45% of first-time purchasers return within a year; ten quarters later, the repeat rate approaches 60%. That’s in contrast to the industry average repeat purchase rate, among its peers, of 46.2% after 10 quarters. See the chart below:

Combine real functional superiority with emotional cachet and distribution discipline, and you create a brand that can command $100+ yoga pants while some peers struggle to clear $70 tags even on a new product’s launch day. Few brands better embody an upper-middle-class lifestyle, for both men and women, than Lululemon.

The Paradox of Premium Retail

The concern with retail, though, is that retail is hard (Daniel hasn’t been shy to remind me of that.)

Plain and simple, retail is arguably the peak of competition in capitalism, and most brands end up being passing fads. You’ll find no argument on that point from me.

Notoriously, “hot” retail brands lure investors in with accelerating sales, strong margins, and viral popularity, only for the brand to suddenly fall apart, reversing the flywheel as inventories pile up and then are discounted, destroying profits (and the brand). In betting on retail brands long-term, the odds are stacked against you, and the fact that we are even considering owning a retail brand for 5 years+ perhaps makes us seem naive to some readers.

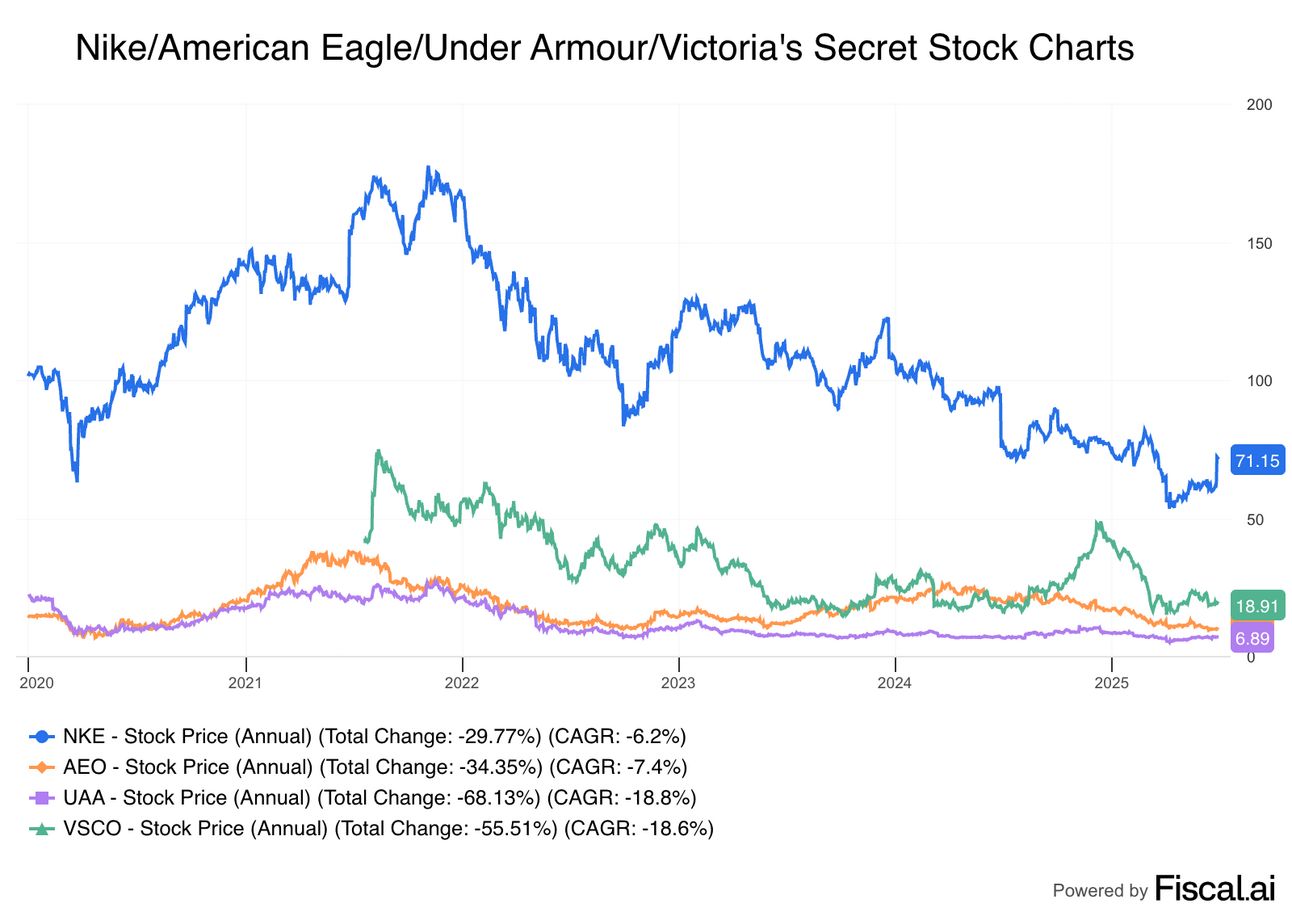

Look no further than Under Armour, American Eagle, Victoria’s Secret, and even Nike, to a lesser extent, in recent years. All promised that, perhaps, “this time is different,” only for the brands to fall into an inevitable downcycle, or worse. See their returns over the last 5 years for yourself:

This is, often, an unfortunate inevitability, and what I call the Paradox of Premium Retail: If a brand starts as having a desirable brand that’s functionally superior but also acts as a status symbol, as the company grows its sales, the brand will become more mainstream and less special to early adopters. For anyone who knows the posh brand Vineyard Vines, just ask them how the expansion into Target several years ago has hampered popularity amongst its original demographic of prep-school attendees, yacht sailors, and country-club goers.

Put differently, as competition enters to mimic a popular brand’s products at lower prices, said popular brand has to lean on discounts (or partnerships with mass retailers like Target) to drive incremental growth, further watering down a brand that has already peaked, until the brand is largely destroyed or goes through a total reset, as American Eagle is currently experiencing courtesy of Sydney Sweeney.

Either way, it’s a vicious cycle that few brands have ever totally escaped, which is why, as we’ll get to in a moment, I think the market is so jumpy about Lulu at the first sign of weakness for a brand that has otherwise been uniquely durable since inception, and has been socially relevant for long enough to, in my opinion, no longer be considered a fad.

Cracks in Lulu’s Direct-to-Consumer Fortress?

So, as we’ve discussed, tight control of distribution feeds Lulu’s moat and positions it to be more enduring than brands that must rely on wholesale, but it also concentrates operational risk. By selling direct-to-consumer (DTC), Lulu owns the narrative, protects pricing, and keeps wholesale partners from dumping overstocks.

Yet, doing so is capital-intensive and demands relentless store-level execution, sophisticated planning, and impeccable inventory discipline.

Two data points show some cause for concern, as markets debate whether Lulu has yet succumbed to the Paradox of Premium Retail.

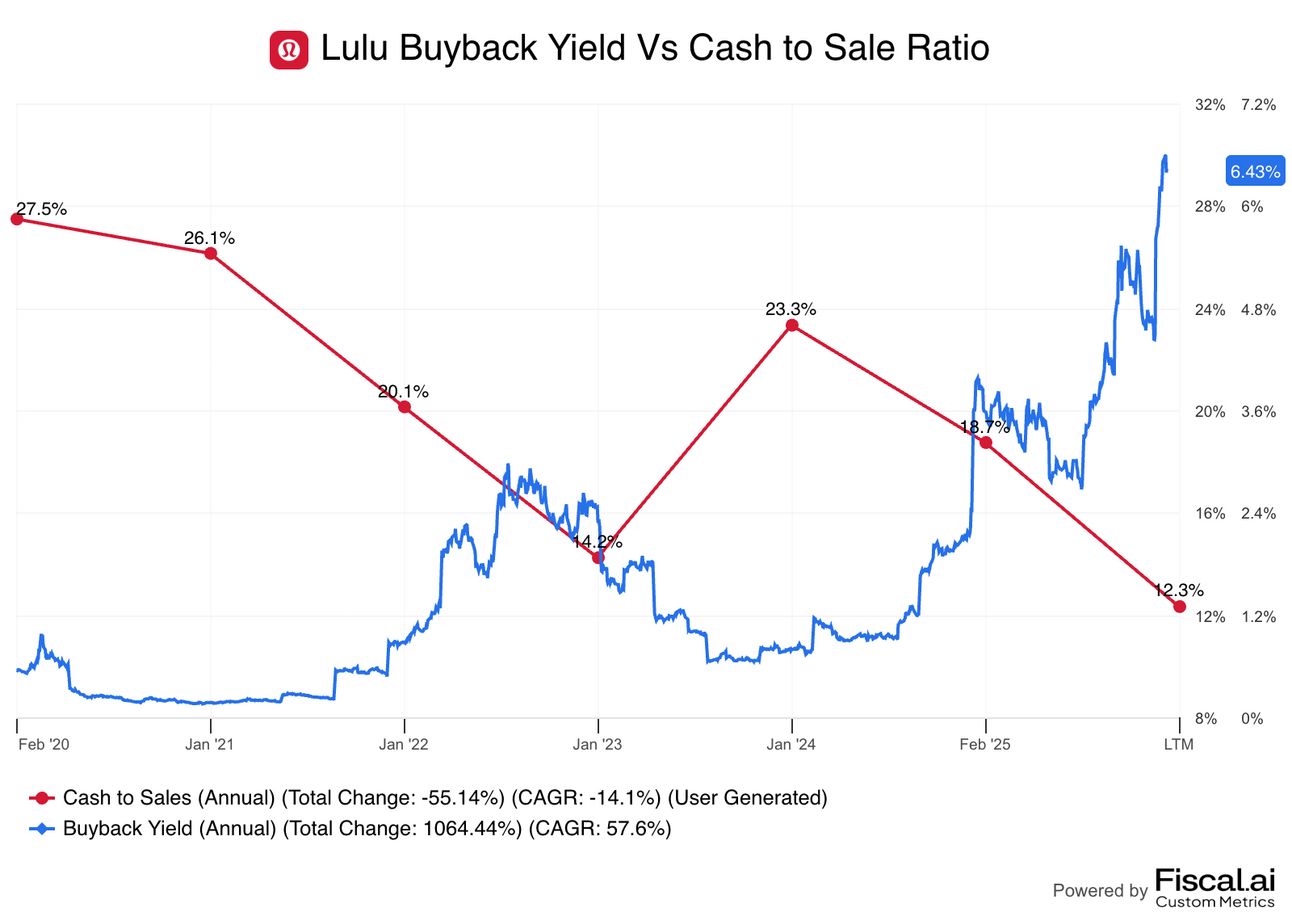

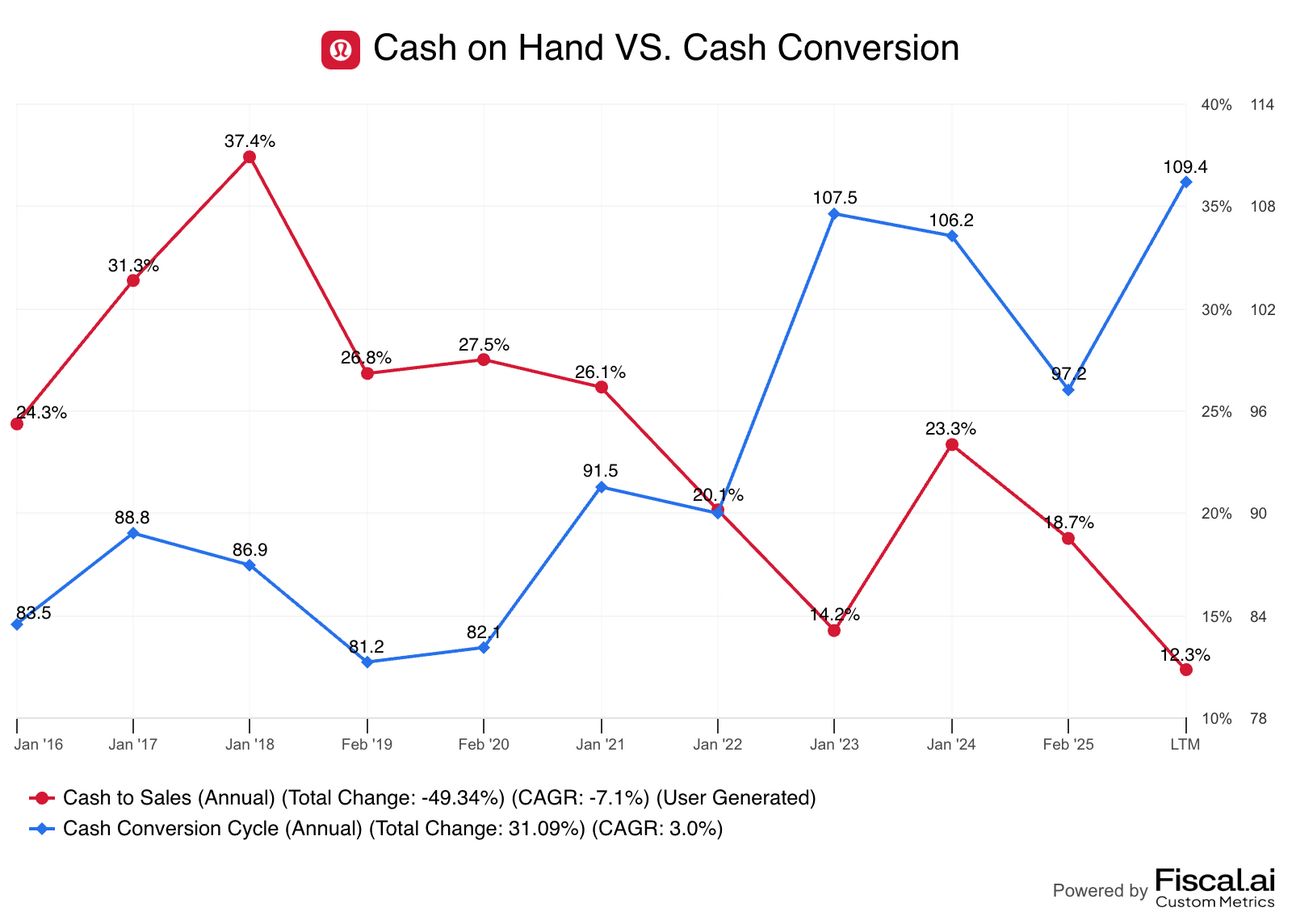

Firstly, the company’s cash-to-sales ratio peaked at 37% in 2017. Each subsequent year, the figure slipped, standing just above 12% today. Management partly explains that trend by pointing to share buybacks and new-store capital expenditure; fair enough.

Still, less cash on hand means reduced shock absorbers if consumer demand softens or tariffs pinch margins, and suggests that the business could be holding onto inventory for longer (not good), leading us to the next data point: Lulu’s widening cash-conversion cycle.

A longer cash conversion cycle is typically bad for retailers

Since 2019, the company’s cash-conversion cycle (how long it takes to collect cash payment from when inventory is first ordered) lengthened from roughly 82 days in 2019 to about 119 days in the last twelve months.

What that means is that more of Lulu’s cash is tied up in inventory, which the company isn’t turning over as fast as it used to, especially as its assortment has broadened beyond women’s yoga pants into golf, tennis, work clothes, men’s outerwear, and footwear.

Add pandemic-era logistics snarls, with the company now structurally looking to keep larger quantities of inventory on hand to navigate macro disruptions, and the working-capital bill has swelled. On the payables side, Lulu lacks the sheer scale of Nike or Adidas while sourcing from more specialty suppliers, so suppliers can demand payment in thirty to forty-five days, not the sixty or ninety days that Lulu’s giant rivals enjoy. The result, again, is that more capital is tied up for longer before a sale converts back into cash.

None of this is damning, but if an investment in Lulu blows up over the coming years, we would likely point back to these indicators as being the signal we should’ve paid closer attention to.

Still, it’s not shocking that A) cash-to-sales has declined (in part from buybacks), B) inventory is sticking on the balance sheet longer (mainly due to offering more types of products beyond their original items) and C) Lulu is more aggressive about stocking up on inventory after war in Europe, tariffs, and a global pandemic have flipped supply chains upside down in the last 5 years.

The bigger picture risk is that if Lulu misforecasts demand on a new clothing line, markdown temptations rise, and discounting (to drive sales to meet short-term Wall St targets) could chip away at the prestige the company relies on.

The Future of Athleisure is…China?

While North America still contributes the majority of Lulu’s revenue, the most intriguing chapter of Lulu’s next decade will be written overseas.

International sales leapt from 16% of revenue to a quarter in just two years. Mainland China already edges out Lulu’s home market of Canada at roughly 13% of global turnover.

Store counts on the mainland are scheduled to rise 75% this year versus 2022, and management regularly reminds investors that China is actually Lulu’s fullest-price market, meaning sales are made there with fewer markdowns than even the United States.

Lulu in China

Management believes half of the company’s revenue could come from outside the Americas before 2035. If so, the narrative that many commentators push, that Lulu is saturating its home turf and can only grow through reckless category expansion, looks incomplete. International mix shift could reignite consolidated growth even if U.S. comps flatten into the low-to-mid-single digits.

In less fancy language, there’s plenty of runway for continued growth for the entire business if Lulu continues to successfully scale the brand overseas.

There is, of course, a flip side. Chinese regulators can turn fickle, as can the Chinese consumer, and Western brands that once seemed unstoppable in China (Coach, Michael Kors) have stumbled when their premium aura dimmed. But yet, for Lulu, premium pricing remains intact, in addition to its industry-leading sales per square foot, as the brand has compounded sales at 46% a year over the last three years in China, and 35% per year internationally outside of China.

Another Tailwind From Menswear?

Management’s 2019 “Power of Three” plan asked investors to believe Lulu could double men’s revenue, double e-commerce, and quadruple international revenue in five years. Four years later, management ticked each of those boxes early. That success birthed the “Power of Three × 2” initiative, which targets another doubling of menswear by 2026.

Today, men’s is now a quarter of sales and still growing by low-double-digit percentages.

Lulu’s brand awareness among U.S. males sits in the mid-30s, though, far below the company’s brand recognition amongst female consumers. That gap spells opportunity, but also requires marketing muscle Lulu has historically avoided wielding. As the company develops technical golf polos, commuter trousers, and a nascent footwear line, it steps onto turf patrolled by Nike, Adidas, On, and countless other challengers, while also going up against Alo and Athleta in yoga, and Vuori, which started, effectively, as Lululemon for men back in the day.

Where menswear could extend the growth curve for years, if Lulu overreaches and pumps inventory into an audience that’s slower to adopt, the misfire would exacerbate the company’s working-capital woes, which would eventually ripple back to hurt profitability.

Either way, as long as demand doesn’t implode domestically for Lulu amongst its core female demographic (which it hasn’t), the company should be able to grow for years to come, from both menswear and international markets, and that is why I find Lulu’s 13x forward earnings multiple to be a bit puzzlingly pessimistic for a stock that was, not long ago, a market darling.

Lulu’s Look in the Mirror

And that brings me to consider what has, and can, go wrong for Lulu. The good news is that Lulu doesn’t typically stray too far from its circle of competence. The bad news is that, when they once did, it was very costly, and hopefully that lesson has now been learned.

When lockdowns confined the world to living-room workouts, Peloton soared and home-fitness start-ups fetched lofty valuations. In mid-2020, Lulu acquired Mirror for roughly $450 million. The vision was promising: sell sleek hardware, offer subscriptions to create recurring revenue, use fitness content to drive more apparel sales, and that would enable Lulu to own people’s attire not just at the gym but at home, too.

Whenever a retailer has the chance to build a SaaS business, assuming it’s a credible opportunity, who could blame them for taking it? I’d also want to transition out of the apparel business, at least as much as possible.

The Pandemic was an interesting time, though, where many companies perhaps got a bit too excited about imagining a new and different version of reality. In Lulu’s case, they imagined one where we all would dish out cash for Mirror screens in our homes, so we can work out virtually from our basements alongside others around the world.

Unsurprisingly in hindsight, adoption didn’t go as planned, and the value of the entire acquisition has largely been written off. One has to wonder why an iPad or SmartTV doesn’t suffice for workout-class streaming, rather than buying a whole new smart Mirror from Lululemon.

To offload this misallocation of capital, Lulu signed a five-year content arrangement with Peloton and quietly moved to sunset Mirror’s stand-alone ambitions. The cash burn dented reported earnings, but the brand damage seems negligible. Fortunately, the average legging-enthusiast never tangled Mirror’s identity with Lulu’s core apparel promise.

Still, the acquisition does serve as a cautionary tale. It reminds investors that empire-building missteps can happen when management strays from their core competence. It also reinforces the idea that Lulu’s best investments remain those stitched from fabric, not silicon.

Valuing $LULU: A Bear’s-Eye View

The bear case is nothing unexpected here. The concern remains that the terminal value of any retail stock is incredibly volatile and fragile, because brands can go from cool to lame in relatively short order, dramatically changing the company’s financial prospects.

To recap from earlier: brands ascend, flood malls, lose exclusivity, then chase volume through discounts that crush margins. Under Armour offers the closest cautionary tale in sports apparel, showing how, once growth slowed, wholesale partners demanded promotions (read: discounts), inventories ballooned, gross margins fell five to six percentage points, and now the stock has yet to recover after becoming a darling in the mid-2010s.

In a Lulu bear case the script would read like this: Core North American demand flat-lines, Alo and Vuori siphon the trend-setting consumer, inventory builds, management leans on new summer sales and Black Friday promos, and gross-margins contract into the lower 50% range (or lower), which drags operating margins back into the teens and crushes earnings per share.

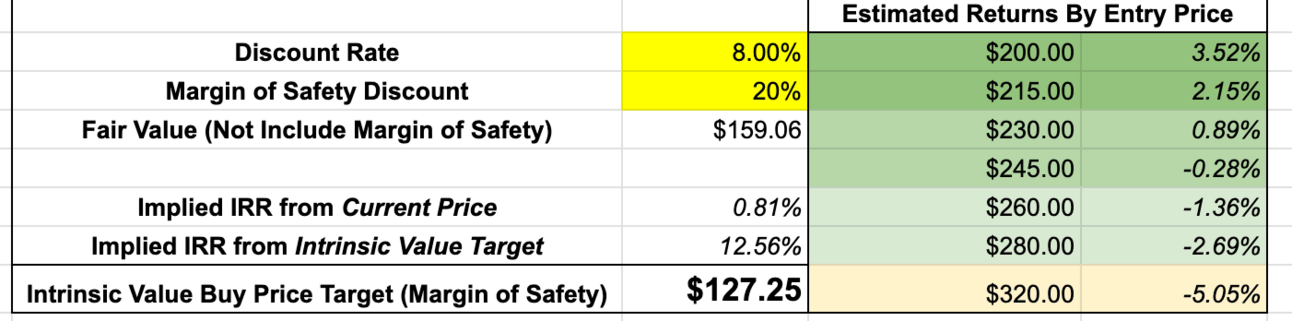

In this worst-case scenario, my model gives Lulu a fair value of roughly $159 a share.

However, a few quick thoughts for the bears: To reiterate again, Lulu doesn’t sell wholesale, and that makes it far less likely they’ll destroy the brand in the same way that Under Armour has. Additionally, its grass-roots approach to community building has genuinely built a more loyal core audience, evidenced by the fact that people go out of their way to specifically shop at Lulu stores, and also by their industry-leading rates of repeat customers.

Lulu’s brand truly resonates, and its products are legitimately higher quality than peers, so while I would never argue that the brand couldn’t go stale in North America and see sales flatlines, I also have trouble imagining Lulu’s financials getting entirely wiped out, which is why I see the worst-case scenario as really only being about 15-20% lower after the stock has already fallen 50% YTD (for plausible worst-case scenarios over 5 years, that ain’t so bad, but is clearly subjective — things can always be worse than I expected).

The Base Case, Bull Case & Portfolio Decision

The bull thesis starts with the observation that Lulu’s present valuation already bakes in a large slice of disappointment. The shares have been dramatically re-rated, as the stock has fallen over 63% since its peak.

Yet, earnings per share did not fall; they’ve grown more than 20% between the stock’s first air pocket and today. The mismatch between fundamentals and Mr. Market’s mood has been stark, which is not to say that the business won’t be hurt by tariffs or that growth rates haven’t started to slow in North America; it’s just that these points may be more than priced in.

Nike, for example, saw its stock surge 18% in a day after management suggested that, over the next year, tariff impacts can be minimized to such an extent that the effect on margins should be relatively marginal.

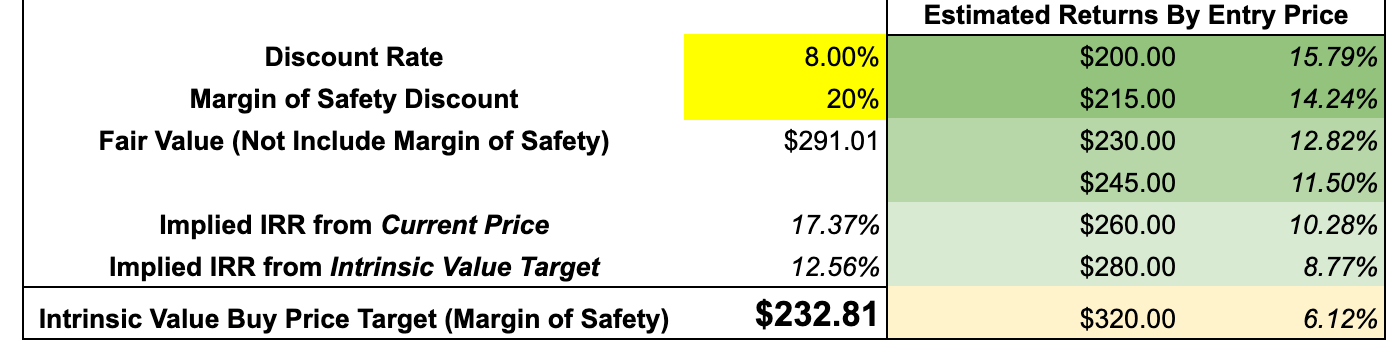

In my base case, I imagine that North American sales slow to just 4% a year over the next 5 years (versus a 14% CAGR since 2021). That is hardly heroic, while I assume international revenues clip along at 18% (half their growth rate in recent years).

I then assume tariffs lop 200 basis points from operating margins and layer in the effects of ongoing share repurchases that shrink the share count by roughly 1.5% annually, in line with management’s track record since 2020.

Those inputs yield a five-year earnings-per-share estimate of about $21.30. If the market one day values that earnings stream at a plain-vanilla 20x P/E, a multiple in line with the S&P 500’s average P/E today, the present fair value of the stock (using an 8% discount rate) would be nearly $300. That implies roughly 60% upside.

Push the scenario to be a bit more bullish, where growth in North America and abroad continue at a healthy pace, while margins remain near 2024 highs, and we get some further mean reversion in the exit multiple to price the stock at 22× 2029 earnings (optimistic but not crazy, assuming Lulu keeps profitably growing), and the fair value today could be as high as $400 per share, implying 100%+ upside.

Long story short, I see the downside as being relatively capped at these beaten-down prices, with an asymmetry to the upside potentially assuming some mean reversion in valuation, and still the chance for above-average returns in a base case while getting to own a fabulous brand with continued growth prospects that, if Nike is any guide, should also be able to absorb tariff costs, especially given its pricing power.

Full disclosure, though: I’m biased by the fact that I love to wear Lulu clothes, my wife and friends love Lulu, and I personally bought the stock several months ago after initially researching it.

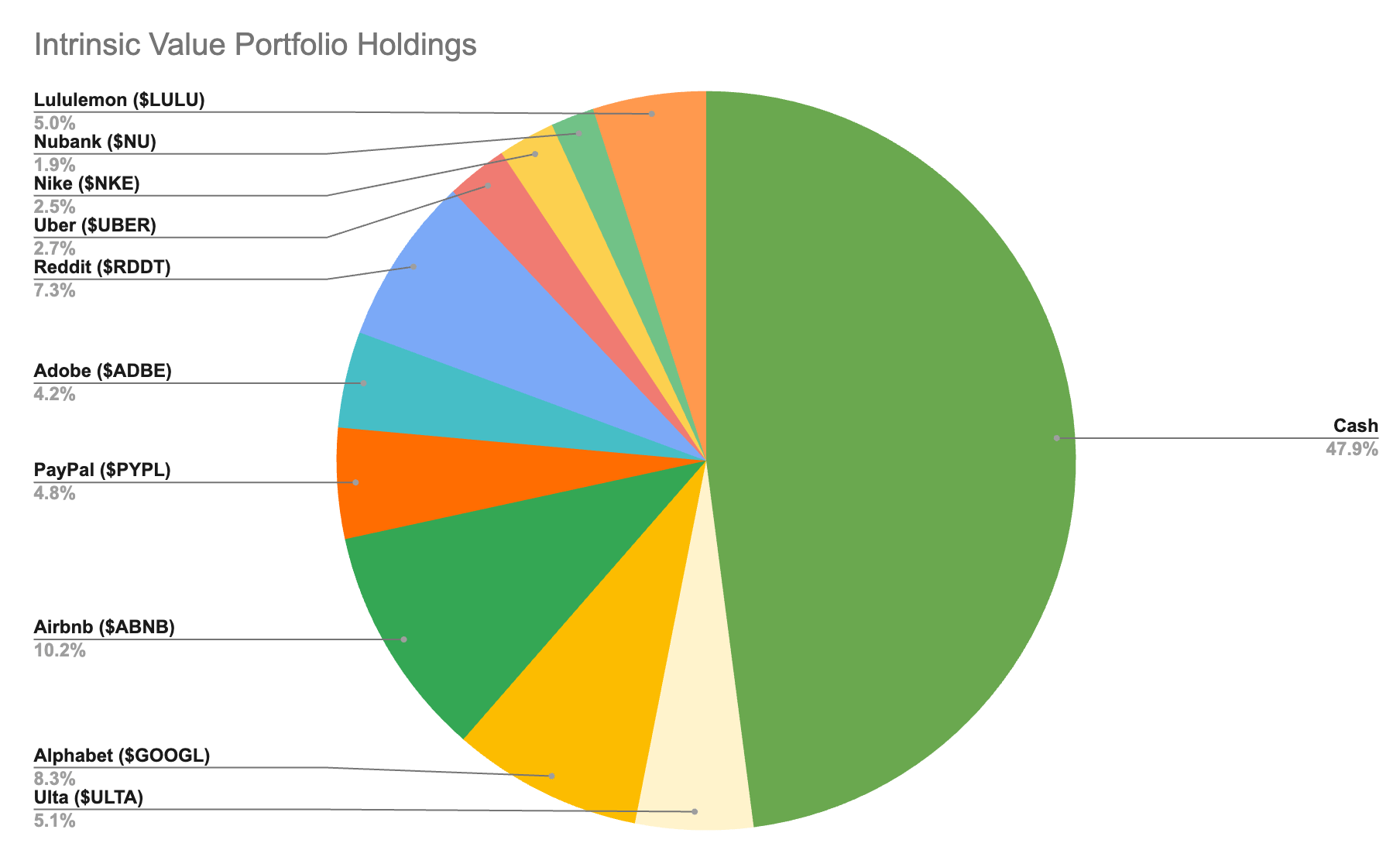

Nonetheless, I’m a buyer of the stock in the current $180-$230 range, and so I pitched Daniel on adding it to our Intrinsic Value Portfolio, and we agreed to add it with a 5% weighting.

For more on Lulu, you can listen to our podcast here, and check out my valuation model for the company here.

More portfolio updates below 👇

Weekly Update: The Intrinsic Value Portfolio

Notes

LULU Position Addition: Given that there’s a several-week gap typically from when we first look at a company and record an episode to when this newsletter is published, sometimes the stock price moves dramatically in that time, and this is one of those cases. When I first pitched Lululemon, its stock was ~$230, and at the time of writing, it has fallen to ~$190. Fortunately, we didn’t dive entirely into the position immediately and have been accumulating a position in LULU in that time, such that our weighted-average cost per share is roughly $204 per share. So we’re starting out a bit underwater on the position already, in terms of presenting the Portfolio here, but we’re glad to have the chance to dollar-cost-average at lower prices. If the stock drops materially lower, we’ll have to reassess whether we want to rebalance/add to the position further.

Coincidentally, on Thursday night, it was revealed that Michael Burry (of Big Short fame) had made $LULU one of his largest portfolio positions.

Update on The Trade Desk: The stock has continued to drift lower this week following a precipitous fall of 40% after reporting earnings last week. It’s a first for us, but having a stock get cut in half to almost exactly hit our fair value estimate days after publishing is, well, funny (and lucky) timing. So are we buying it? Well, we kicked the can last week, and after speaking with a friend who is an expert on TTD and ad tech more broadly, I came away, frankly, even more unsure of the industry’s future, and not at all reassured about TTD’s prospects.

In short, there’s the potential for Amazon & Google to put competitive pressure on TTD, eating away at the hefty 20% take-rate that the company earns as a commission on the ad spend it facilitates. Layer over that the CFO’s abrupt departure, while CEO Jeff Green continues to hold voting power over the company via a dual-share-class structure, and it feels like you’re making a very concentrated bet on Green, himself. And that may or may not be a good bet, but given how the company’s rollout of Kokai has flopped in some ways (the more scuttlebutt I do, the worse it sounds for Kokai — few in the industry seem to happy with it), with Kokai likely being the brainchild of Green (speculation on my end), then there’s real reason for pause. Or, if it turns out the CFO left because of accounting inconsistencies that will be revealed in the coming months, well, that would be even more troublesome (again, completely speculating.)

Long story short — where there’s smoke, there’s fire, and there seems to be smoke coming from TTD, and I’m not ready to bet on the company until I’m confident that everything is under control. But if you missed our newsletter on TTD, you can find it here.

Quote of the Day

"Your culture is your brand.”

— Tony Hsieh

What Else We’re Into

📺 WATCH: Is McKinsey losing its crown to AI?

🎧 LISTEN: Should value investors own index funds?

📖 READ: The Calculus of Value, Howard Marks’ latest memo + Berkshire adds position in UnitedHealth

You can also read our archive of past Intrinsic Value breakdowns, in case you’ve missed any, here — we’ve covered companies ranging from Alphabet to Airbnb, AutoZone, Nintendo, John Deere, Coupang, and more!

Your Thoughts

Do you agree with the Portfolio decision for Lululemon?Leave a comment to elaborate! |

See you next time!

Enjoy reading this newsletter? Forward it to a friend.

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here.

Use the promo code STOCKS15 at checkout for 15% off our popular course “How To Get Started With Stocks.”

Follow us on Twitter.

Read our full archive of Intrinsic Value Breakdowns here

Keep an eye on your inbox for our newsletters on Sundays. If you have any feedback for us, simply respond to this email or message [email protected].

What did you think of today's newsletter? |

All the best,

© The Investor's Podcast Network content is for educational purposes only. The calculators, videos, recommendations, and general investment ideas are not to be actioned with real money. Contact a professional and certified financial advisor before making any financial decisions. No one at The Investor's Podcast Network are professional money managers or financial advisors. The Investor’s Podcast Network and parent companies that own The Investor’s Podcast Network are not responsible for financial decisions made from using the materials provided in this email or on the website.