- The Intrinsic Value Newsletter

- Posts

- 🎙️ Chapters Group: Buying Constellation Software 20 Years Ago?

🎙️ Chapters Group: Buying Constellation Software 20 Years Ago?

[Just 5 minutes to read]

Most weeks, we focus on large and well-established companies. Sure, we like to look at them when the market doesn’t like them, but at the end of the day, these are still big businesses operating in the most successful stock market in the world: the U.S.

Today, we’re doing something different. Instead of an American mega-cap, we’re looking at a German serial acquirer of software companies with a market value of roughly $1 billion. Despite its size, it shares a surprising number of traits with some of the greatest compounders in history — and it has one of the most impressive investor bases of any company we’ve covered so far.

Chapters Group is often referred to as the “new Constellation Software.” So the question today is whether buying Chapters could realistically turn into one of those rare, multi-decade compounding stories.

Could it be a 100-bagger over time?

Honestly, Shawn and I are not particularly greedy people, so we’d be perfectly fine with a 50x…

Let’s dive in!

— Daniel

Chapters Group: Constellation Software all over Again?

Usually, when we cover a company, most of you already have a good sense of what it does — even if you’ve never been a customer yourself. This time is a bit different. Today’s company is a German small-cap based in my hometown of Hamburg, and it’s a serial acquirer of mission-critical software businesses. In other words, it’s often described as an early-stage Constellation Software.

I know — that’s a dangerous comparison. It’s a bit like calling Lamine Yamal the next Lionel Messi: technically possible, but almost unfair at such an early stage. And if European football isn’t your thing, think of all the young quarterbacks who were once labeled the “next Tom Brady” and never even came close.

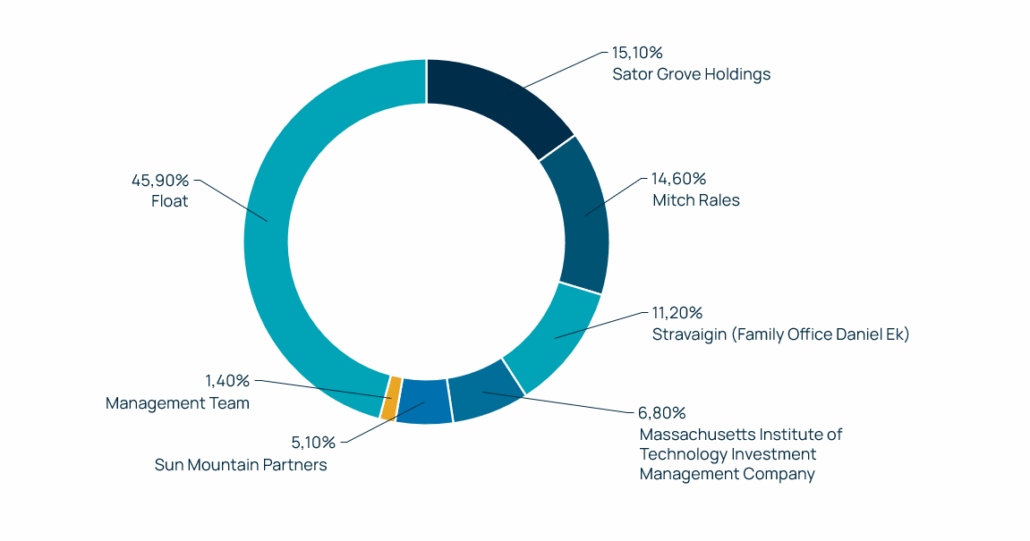

But Chapters has a very unique thing that immediately grabbed my interest – its shareholder structure. Just take a look at it yourself:

In case you didn’t know those names, let me explain.

Mitchell Rales is best known as the co-founder of Danaher, one of the most successful acquisition-driven compounders of the past 40 years. It was built through decentralization, disciplined capital allocation, and relentless operational benchmarking. In many ways, Rales helped define what we now call “programmatic acquirers.”

Today, Rales has largely stepped back from day-to-day operations and is focused on investing his own capital. He has publicly stated that he’s actively looking for potential 100-baggers — businesses where he can not only invest money, but also contribute experience.

Another name on the list is Daniel Ek, the founder and CEO of Spotify. It’s not a serial acquirer, but certainly a 100-bagger. Ek owns just over 11% of Chapters through his family office.

And then there’s Sun Mountain Partners, a fund run by William Thorndike. Thorndike is best known for his work on exceptional CEOs and capital allocators — a topic he covered extensively in The Outsiders, which loyal listeners of the podcast already know is one of Shawn’s and my favorite books.

Mitch Rales (Left), Daniel Ek (Middle), William Thorndike (Right)

Even MIT appears on the register, which is not exactly typical for a small-cap German serial acquirer.

So hopefully you can see why it took me all of about 20 minutes to get interested when a member of our Intrinsic Value Community reached out and asked whether I had heard of this company before.

Of course, a strong shareholder base alone doesn’t make an investment attractive. But it raises the bar and makes the entire case much more interesting from the start.

To really understand what’s going on here, it helps to take a quick look in the rearview mirror and see how this company came to exist in the first place.

History and Founding Story

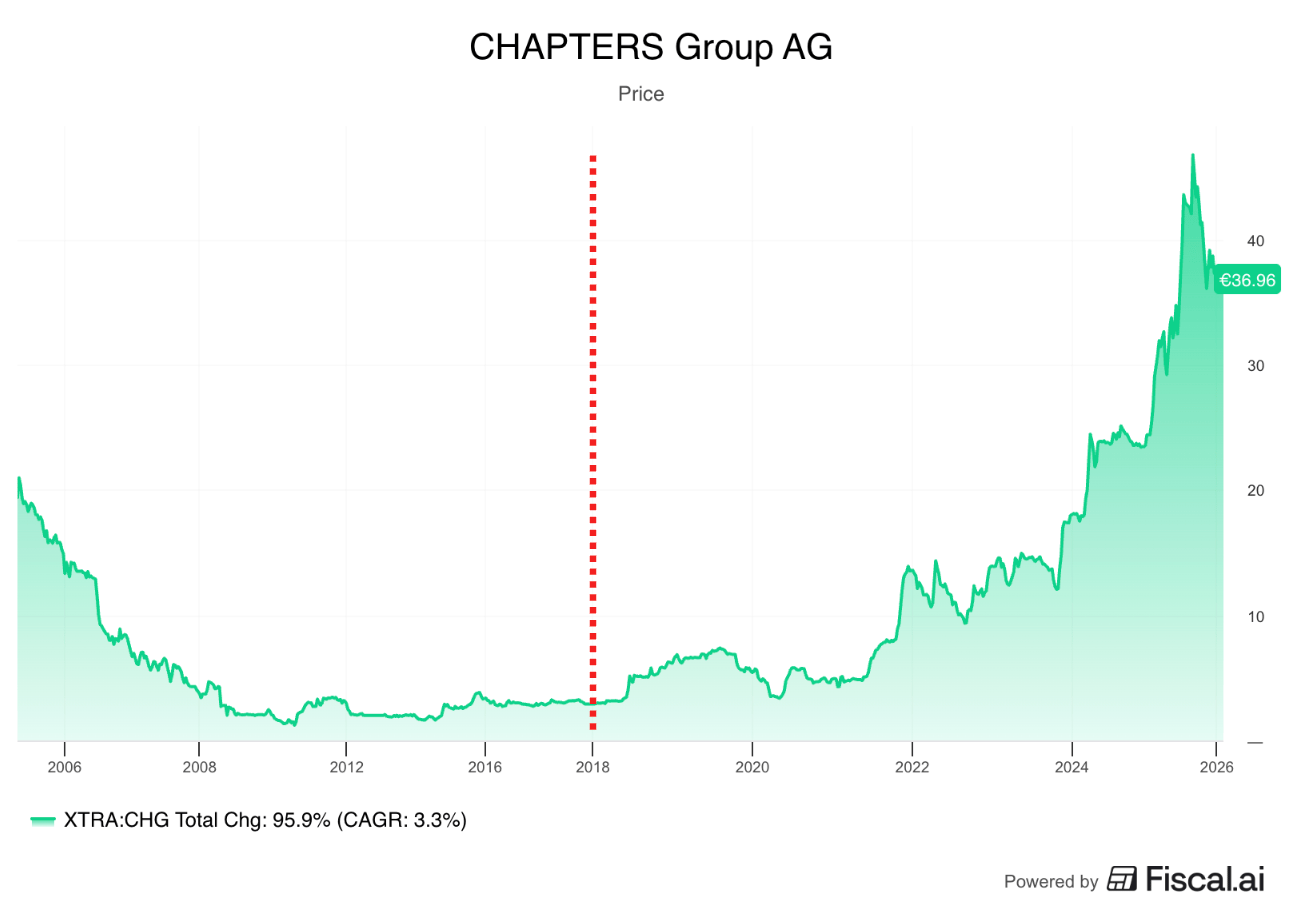

If you look at Chapters stock chart, you might find yourself asking: “What is going on here? What happened around 2018 that turned a clearly deteriorating business into one that went on to surge in the years that followed?”

The answer is a fundamental restructuring. Chapters was previously called MEDIQON Group AG and operated in the healthcare and medical supplies space — a capital-intensive, operationally demanding business with very little resemblance to what the company stands for today.

The red line marks the restructuring in 2018

That chapter (pun intended) effectively ended in 2018. In that year, Mediqon sold its remaining operating assets, leaving a public listing and a balance sheet with capital, but no operating business.

When that happens, you can either liquidate and return capital or use a listed shell as a vehicle to build something new. And that’s what a group of anchor shareholders did.

In the beginning, the new holding company didn’t have a very structured plan besides investing in small, profitable businesses across different industries in the DACH region (Germany, Austria, Switzerland).

At this point, the company looked like one of many holding companies that would eventually trade at a discount to Net Asset Value (NAV) because of the diverse companies and industries under its umbrella. Markets don’t really like these sorts of holding companies because they’re complex, and success with one company or trade doesn’t necessarily translate to the others.

However, markets are willing to pay premiums for programmatic acquirers with a clear idea of the type of company they look for and an equally clear M&A strategy and playbook.

Jan-Hendrik Mohr realized that as well. He took charge of the group of anchor shareholders and led the company's reorientation. At only 36, he’s a young CEO. Still, he is quite experienced. He studied Buffett for decades and ran his own fund before becoming Chapters’ CEO.

Fortunately for us, he didn’t adopt Buffett’s aversion to software companies. And that’s exactly the space he should lead Chapters into. He recognized that the best business models they looked at were software companies, specifically vertical-market software (VMS), and decided that’s the direction Chapters should take.

They were more resilient, required less incremental capital, and, crucially for a small holding company, could be left largely autonomous while still generating attractive returns.

Okay, let’s take a look at the types of companies they own and the structures under which they own and operate them.

Business Breakdown

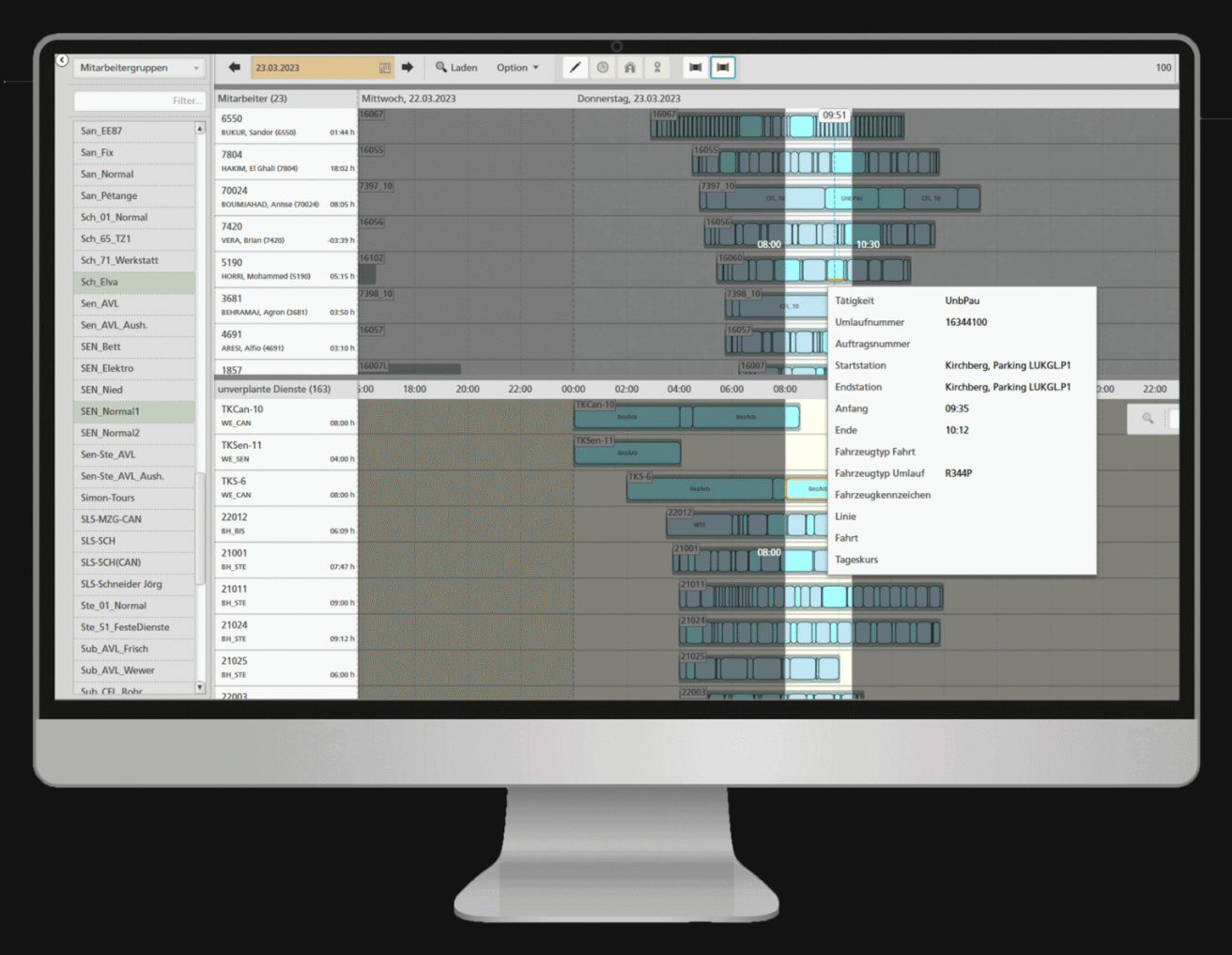

A good example of the type of company Chapters owns is PEAK Mobility. It’s a company providing software for public transport operators. Its products are used to manage depots, vehicle scheduling, personnel planning, and real-time operations. If they fail, buses don’t run, and trains don’t leave the station.

And speaking as a European, that would effectively shut down entire cities. I don’t even own a car. If PEAK Mobility stopped working, I wouldn’t be able to get around Hamburg at all. That’s really the point: this is about as sticky a customer relationship as it gets. There is absolutely no appetite for “trying out” new software in this context.

Procurement cycles in this space are long, contracts are sticky, and once a system is implemented, it often stays in place for decades.

PEAK Mobility Software

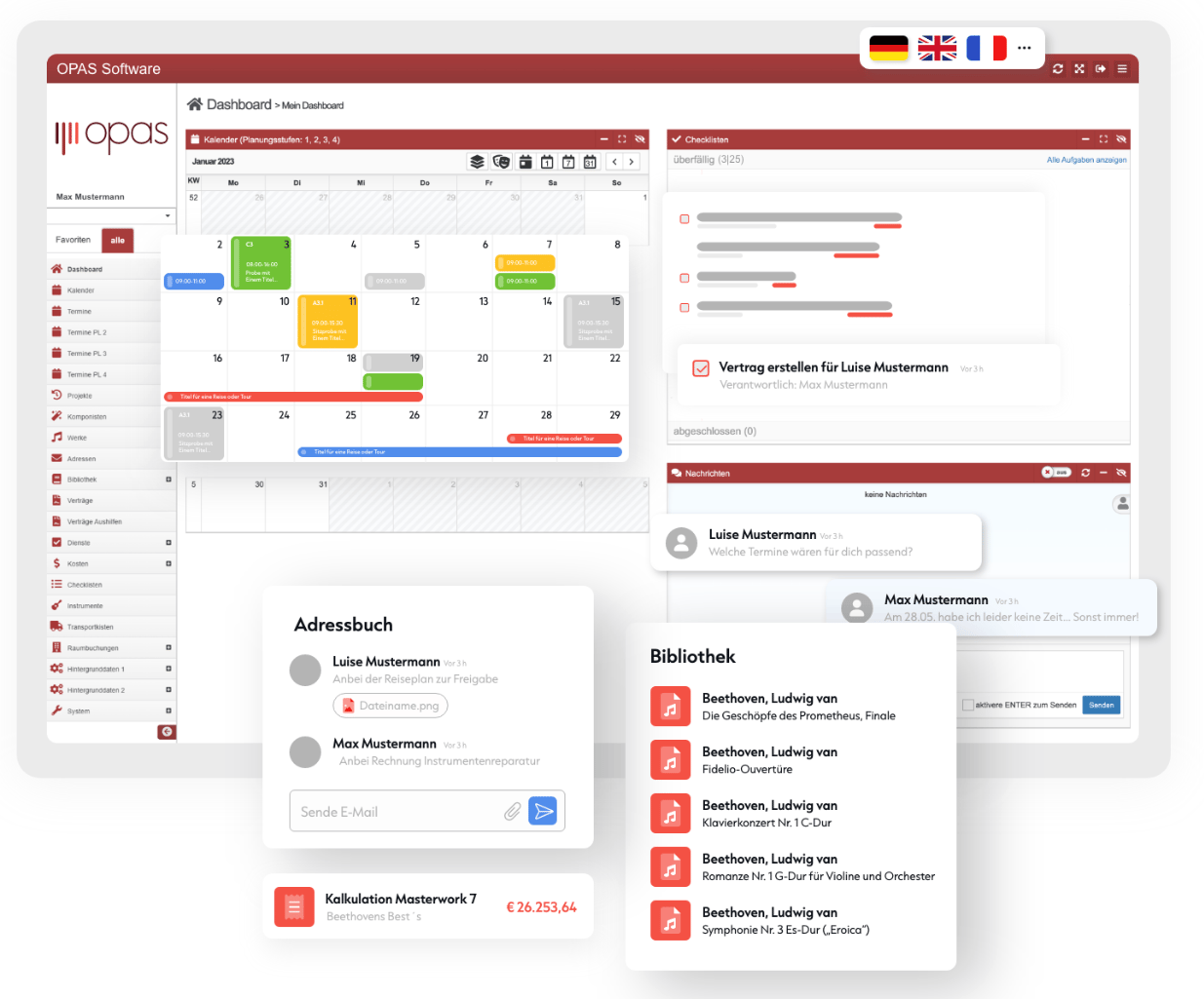

An example of a company serving private-sector customers is OPAS Software. OPAS is a global leader in orchestra software and is used by more than 250 institutions worldwide. At first glance, that might sound so niche that it borders on irrelevant. But that’s exactly what makes it attractive.

When we talked about TransDigm a couple of weeks ago, I mentioned a dynamic that shows up again here: the most attractive economics tend to sit with the company that dominates a very narrow niche. These markets are often too small to support many profitable players, which makes them unattractive for second movers. If you’re not already the incumbent, it’s usually not worth entering at all.

Many of Chapters companies follow a similar pattern, not to the same extreme as TransDigm, but close enough for the analogy to hold. They operate in highly specialized or regulated environments where customers have little incentive to ever switch providers. Once the software is embedded in daily workflows, stability and reliability matter far more than marginal improvements, and that’s what creates the long-term stickiness these businesses rely on.

OPAS Software System

There are two situations in which Chapters most often acquires companies. The first is a succession problem, typically when a founder or long-time CEO can’t find a suitable successor. The second is a carve-out, where a business is spun off from a larger parent company and no longer fits its owner’s strategic focus.

Because of its size, Chapters is still operating primarily in the micro- to small-cap space. That means it rarely competes directly with private equity. And even when it does, founders often prefer selling their life’s work to Chapters rather than to a private equity buyer who might slash costs, aggressively raise prices, and aim to flip the business a few years later.

When we get to the structural tailwinds, we’ll talk in more detail about why this dynamic creates a deep and durable deal pipeline, especially in Germany, where succession issues are becoming more acute, and Chapters’ acquisition playbook is particularly well-suited.

For now, let’s zoom in and walk through what actually happens when a single company joins the group and how the integration process works in practice.

The Integration Process

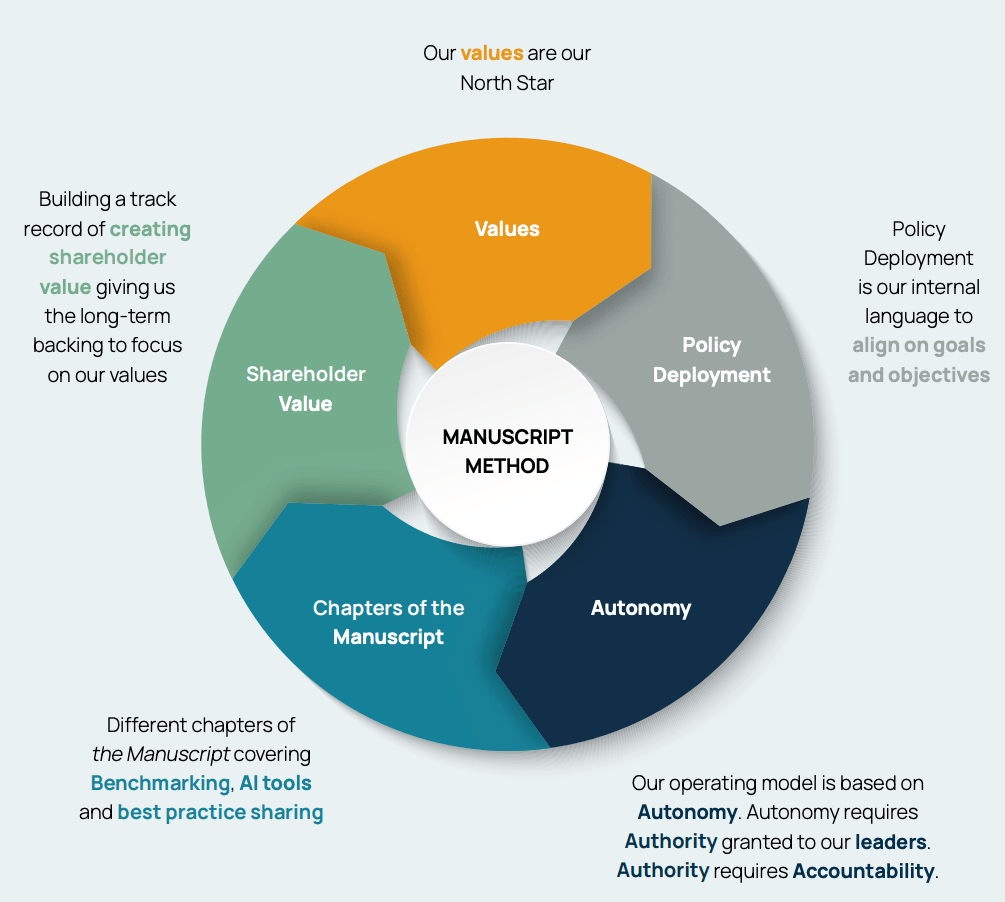

Once a company joins the group, it is deliberately not “integrated” in the classic corporate sense. There is no forced rebranding, no centralized sales team, and no headquarters dictating day-to-day decisions. Instead, Chapters operates through what it calls the Manuscript Method.

The Manuscript Method is essentially an operating system built around a simple trade-off: autonomy in exchange for accountability. Local management teams retain full responsibility for running their businesses, keeping decisions close to the customer and the market they operate in.

At the same time, performance is measured in a standardized way across the group. Pricing, margins, organic growth, and capital efficiency are tracked consistently over time. Best practices are shared across the portfolio, and underperformance is identified and addressed early without stripping away entrepreneurial responsibility.

In that sense, Chapters behaves a lot like TransDigm, Constellation, or Danaher. In fact, it was Mitch Rales who helped set up this system.

Capital allocation is another central piece of the model. Acquisitions are typically financed through a mix of equity and shareholder loans. These loans come with an interest rate of 10%.

At first glance, a 10% interest rate looks high, especially for a group that otherwise emphasizes long-term thinking and partnership with founders. But there’s a good reason for this concept. Multiple, actually. These loans are not meant to maximize interest income at the holding level. They are designed to hard-wire capital discipline into the system.

By attaching a meaningful cost to capital, Chapters makes very clear that capital is scarce and must earn its keep. Management teams are incentivized to reinvest only where they genuinely expect returns well above that hurdle rate.

Just as importantly, the 10% loans create a natural decision filter. If a subsidiary cannot reinvest capital at attractive returns, it is encouraged to return excess cash to the holding company rather than pursuing growth for growth’s sake. That capital can then be redeployed into new acquisitions where returns are higher.

Beyond structuring individual acquisitions, you also need a stable corporate setup to scale the business. Chapters organizes its businesses across three broad areas: Public Sector, Enterprise, and Financial Technologies. Within those segments, acquisitions are held and managed through so-called “Platforms,” which serve as the structural backbone for scaling the group while maintaining clear accountability and capital discipline.

In most cases, Chapters holds a majority stake in the platform, and the platform, in turn, owns the shares of the operating businesses beneath it. Acquisitions are executed at the platform level, not directly by the listed parent.

Each platform has its own management team and a clearly defined strategic focus, whether that is a specific market vertical, a geographic region, or a combination of both. The platform teams are responsible for sourcing deals, conducting due diligence, negotiating transactions, and overseeing the long-term development of the companies within their scope. But Chapters remains the capital allocator.

Structural Tailwinds

One of the things that makes me most bullish about Chapters — beyond its shareholder structure, the quality of the companies it owns, and the management team, which we’ll get to — is the set of structural tailwinds working in its favor.

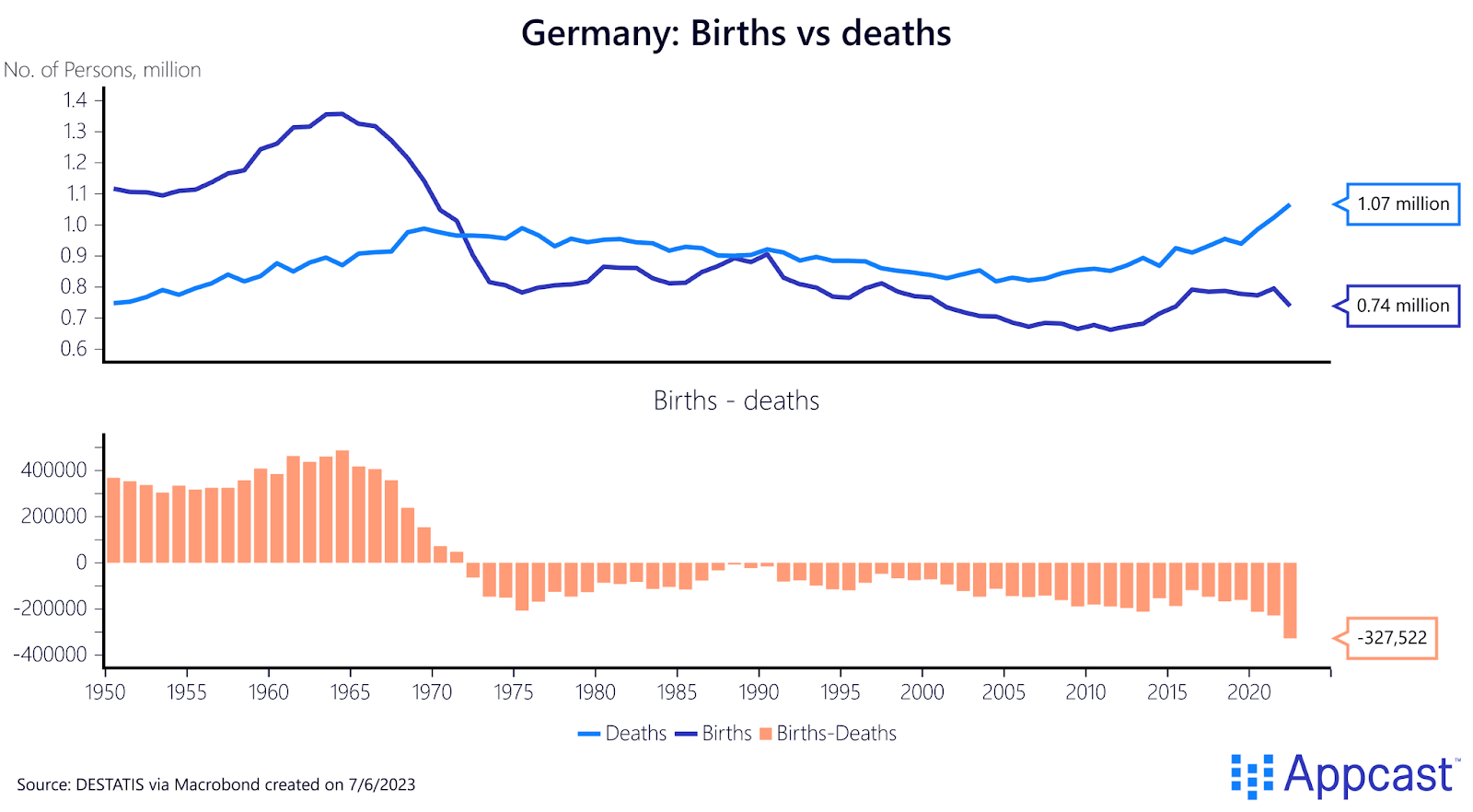

One of the most important of those tailwinds is demographics. That might sound counterintuitive, because demographics are often cited as one of Germany’s biggest challenges. But in Chapters’ case, that very problem creates multiple avenues for long-term opportunity.

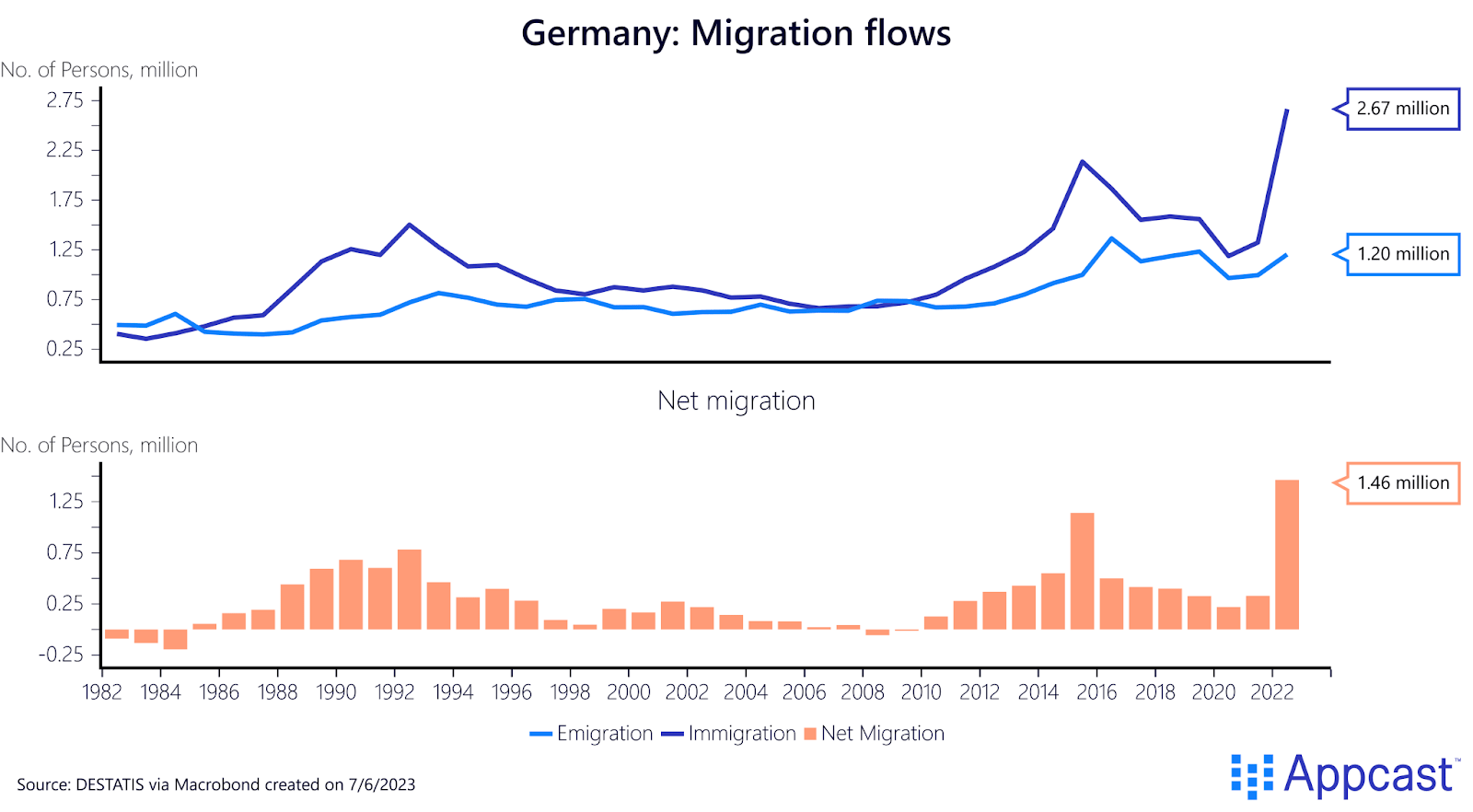

Germany is aging rapidly. The median age is 45, the domestic working-age population is shrinking, and large cohorts (the boomers) are approaching retirement. Without sustained immigration, Germany’s labor force would decline materially over the next decade. As a result, Germany has become structurally dependent on immigration.

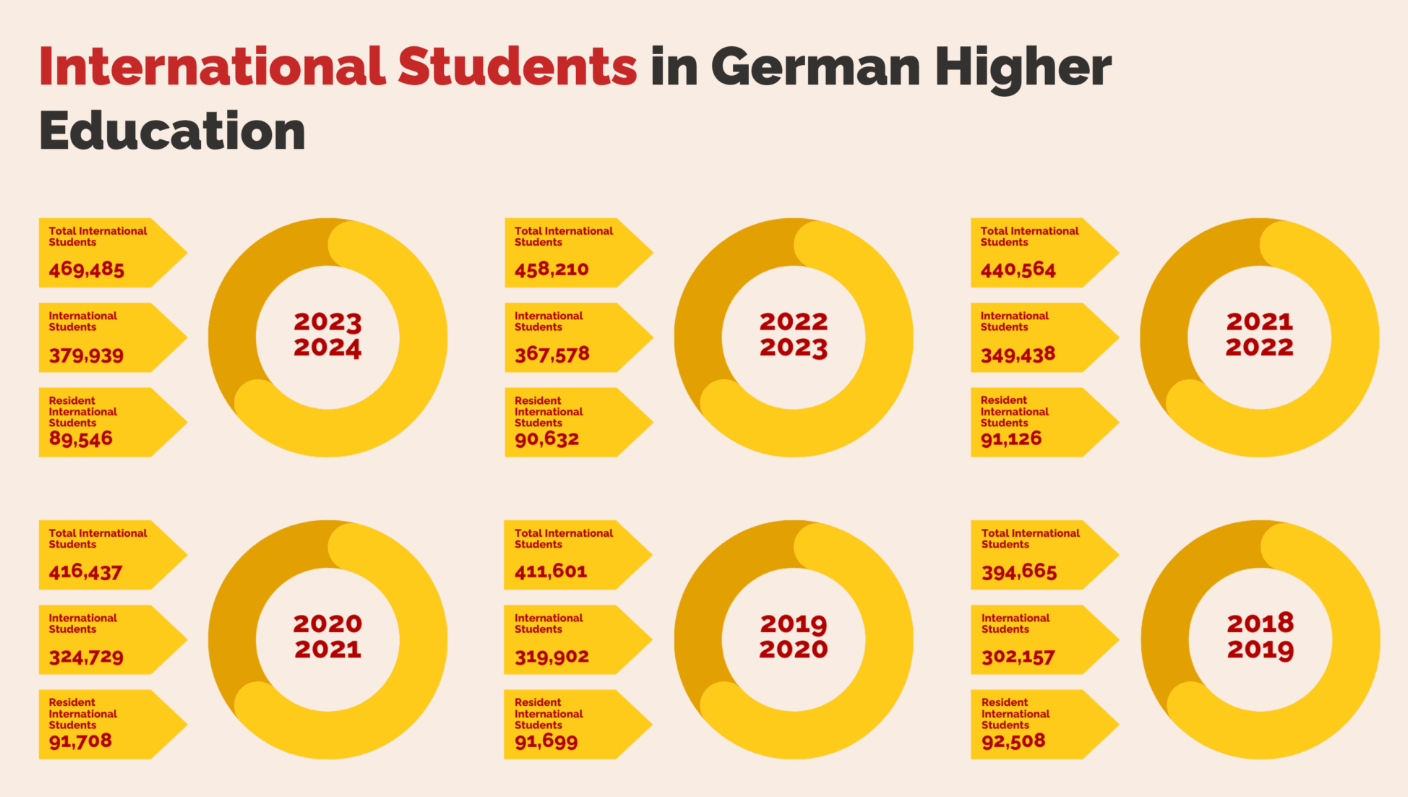

Every year, several hundred thousand people move to Germany for work, education, or training. International students alone number in the hundreds of thousands, making Germany the most popular non-English speaking study destination globally.

Roughly half of those international students are still living in Germany ten years after starting their studies. That’s an important data point when looking at Chapters’ third business arm: Financial Technologies — and specifically Fintiba.

Through Fintiba, Chapters pretty much owns the entire onboarding process for international students and expats. And that process is anything but frictionless. I remember stories from international students at my student apartment complex… And let me tell you, immigration into Germany can be a bureaucratic nightmare.

Before even arriving, students and expats have to prove financial solvency through a so-called blocked account, secure health insurance, and comply with a dense set of regulatory requirements. And it doesn’t get much better once they’re in Germany. Accounts need to be maintained, documents renewed, and status changes handled correctly.

Fintiba sits right at the center of this complexity. It provides regulated financial and administrative services that are required by law for many migrants to even enter the country.

The benefit here is that there is no discretionary adoption curve, no race to subsidize users, and no dependency on marketing spend. Demand is created upstream by demographics and regulation. And since hundreds of thousands of international students stay in Germany and have done all their onboarding and finances through Fintiba, there’s a huge opportunity to monetize them for many, many years.

At the same time, regulatory complexity acts as a moat. Integrating with official processes, maintaining compliance, and building trust with authorities takes time. Once a platform is embedded, it becomes very difficult to replace, not because of brand loyalty, but because of institutional inertia. And from a customer perspective, you obviously tend to stick with the service that made all the onboarding much easier.

So demographics and migration are very tangible tailwinds for the Financial Technologies arm of Chapters. But the demographic shift cuts another way as well, and this one directly feeds the acquisition pipeline.

The simple reality is that far more people are retiring than entering the labor force. And in Germany, that imbalance becomes clear when founder-led businesses suddenly face a succession problem. In many cases, there is no internal successor and no family member willing to take over.

That matters because Germany is home to the so-called Hidden Champions: mid-sized companies that dominate narrow global niches. No other country comes close in sheer numbers. While many of these businesses are in manufacturing, there is also a meaningful subset of VMS companies that fit Chapters’ acquisition criteria very well.

Today, many of these companies are still too large for Chapters to acquire. But over time, as Chapters grows, it can find great opportunities there. So instead of deal flow becoming harder at scale, there’s a whole universe of highly successful, suitable acquisition targets.

Risks – AI Threat and Dilution?

When talking about a software company in 2025, we obviously have to talk about AI. But if you’ve listened to our podcast for a while, you already know Shawn’s and my take on this. And, conveniently, Jan-Hendrik Mohr seems to agree with us as well.

Jokes aside, in a presentation he gave at a Serial Acquirer Conference hosted by Chris Mayer, he made a point that really resonates: AI is far more likely to find its way into customer workflows through the software companies that already own the relationship, the trust, and the underlying systems — not through entirely new entrants trying to replace them.

Think about it for a second. Is the HVV, Hamburg’s public transportation network, really going to cut ties with a software provider it has worked with for decades and hand over all of its mission-critical workflows to a brand-new AI startup?

I see the probability of that happening as very low. The operational risk would be enormous, and there’s simply no incentive to take it. Especially in the public sector, decision-makers are not rewarded for choosing the cheapest or most experimental option. They are rewarded for systems that work — reliably and predictably.

What’s far more likely is that productivity gains from AI show up through incremental improvements: new features, smarter planning tools, better forecasting — all embedded into the existing software systems that customers already rely on.

The same logic applies to the Enterprise side of the portfolio. Given the mission-critical nature of many of these businesses, it’s extremely unlikely that customers would rip out their core systems in favor of an unproven alternative. How likely is it, really, that an orchestra decides to shut down its entire operational setup just to replace OPAS Software, arguably the best system in the market, with a new AI system?

If anything, these niches are so specialized that building a viable alternative would require deep domain knowledge and a full software stack from scratch. Even with AI, you still need experienced software engineers to design, integrate, and maintain such systems. And while I’m no expert on orchestra venues, I’m fairly confident that software engineers are not part of the average orchestra’s in-house staff. Hiring them externally would almost certainly make things more complex and more expensive — not cheaper.

So rather than seeing AI as a disruptive threat, it’s far more realistic to view it as an “enabling layer” that strengthens incumbents with embedded software, deep customer relationships, and decades of domain expertise. So basically, exactly the kind of companies Chapters owns.

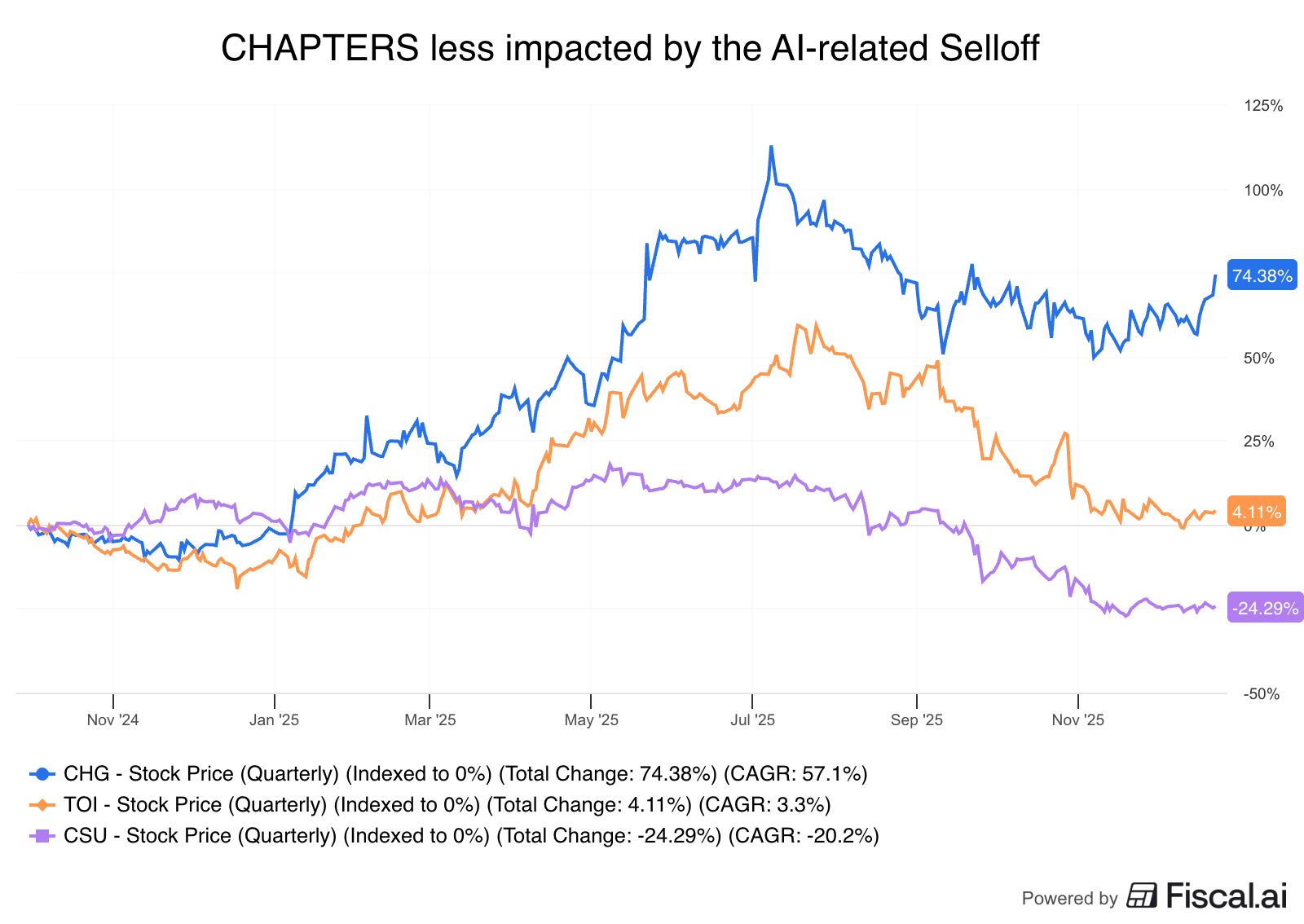

Having said all that, Chapters has surprisingly been spared from the AI-related selloff that companies like Constellation and Topicus have seen anyway.

Another potential risk is dilution. I say “potential” because I’m very confident that management has this under control. However, not mentioning it when there’s this chart would be reckless as well:

Chapters grew primarily through acquisitions. When that’s the case, you need a steady supply of capital. That capital can come from retained cash flows, debt, or new equity.

And when a company is as young as Chapters, meaning lots of growth ahead and, at the same time, not a lot of retained cash flows, equity issuance can be the best way to get capital. Of course, the risk is that new capital could be raised faster than value is created. Over the long run, this would destroy value per share. In other words, the business can be doing the right things operationally while shareholders still experience disappointing returns.

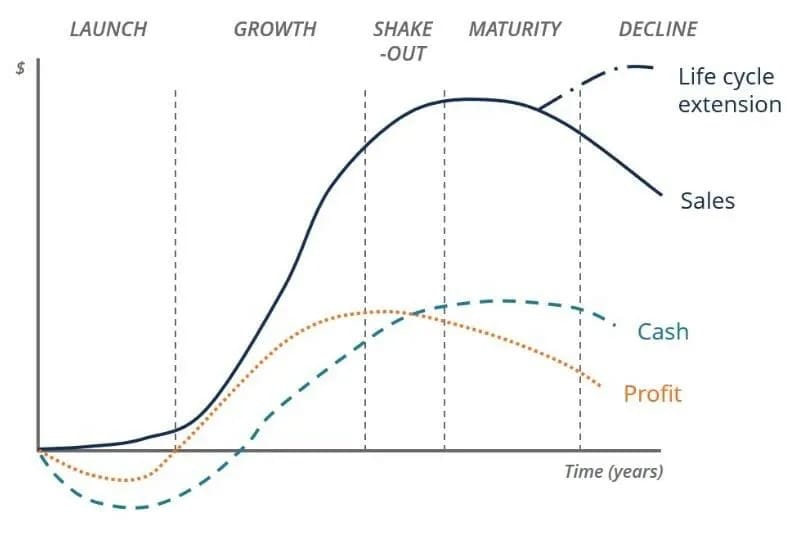

So the key question is whether the returns on invested capital can consistently exceed the cost of that dilution. Management is clearly aware of this trade-off. Jan-Hendrik Mohr has repeatedly said that he optimizes for value per share and that there are different stages in a company's lifecycle. The beginning might come with a lot of dilution, but also with fast growth to offset it. Many years down the road, share buybacks can reduce the sharecount again.

Chapters is at the very beginning of the Growth Phase

This might seem like something management would say to justify dilution today, but I really get the feeling that the CEO is in this for the very long-term. In recent years, dilution has already slowed significantly. The sharp increase in its early years has been due to Mediqon's restructuring into Chapters and its change in business model.

What strengthens my conviction that dilution is not a problem here is that all major shareholders participated in the new equity issuances and even paid premiums to retain their stakes in the company. So the experts are clearly believing it’s the right decision.

Speaking of Chapters as an investment, let’s talk a bit about the financials and the valuation.

Financials & Valuation

The problem with valuing Chapters is that the company is in its early stages. One reason we tend to look at more mature companies is that the range of possible outcomes is much narrower.

The key metrics to look at right now are revenue, EBITDA, and invested capital growth. Revenue compounded at a CAGR of over 60%, EBITDA 50%+, and Invested Capital 70%+. This is why I’m okay with the current levels of dilution. If we just look at the last two years, revenue and invested capital have grown more than twice as fast as dilution.

Beyond M&A-driven growth, a serial acquirer ultimately has to deliver organic growth as well. Looking at Chapters’ portfolio companies, organic EBITDA growth for 2025 is expected to be in the low teens, which is an encouraging signal.

That said, it will likely take time for this level of organic growth to show up consistently at the group level. Newly acquired companies don’t immediately benefit from the full Chapters playbook.

Integration takes time, and the impact of the Manuscript Method, pricing discipline, and capital allocation policies tends to materialize gradually rather than all at once. As more portfolio companies mature within the ecosystem, organic growth should become a more visible and stable contributor to overall value creation.

You might ask why we don't look at EPS, since I mentioned before that management, especially CEO Jan-Hendrik Mohr, focuses most on value per share. The reason is that EPS has been quite volatile due to accounting effects coming from the rapid expansion of the business.

The main driver is acquisition financing. Interest expenses from shareholder loans and external debt hit the P&L immediately, while the earnings contribution from newly acquired companies often lags. In periods of heavy acquisition activity, this timing mismatch alone can materially depress reported EPS.

A second factor is purchase price allocation. Under German accounting rules, acquired software, customer relationships, and brands are capitalized and amortized over several years. These non-cash charges increase automatically as acquisitions accelerate and reduce reported earnings — even when underlying cash generation improves.

And of course, dilution matters too. When new shares are issued, this pressures EPS further since the earnings are divided among more shares. Because of all that, EBITDA is the better measure to look at right now.

And still, valuing Chapters is difficult. No history of earnings we could work with, volatile growth tied to the number of acquisitions, and possible dilution along the way.

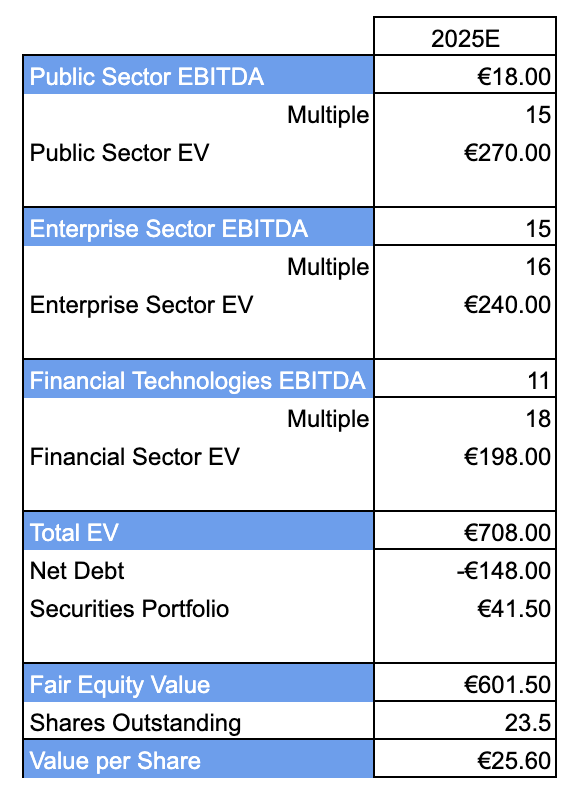

So instead of trying to forecast earnings, let's do a very rough sum-of-the-parts valuation. This will be very vague, since we don’t do much more than look at EBITDA numbers and apply a multiple, but we could spot outrageous under- or overvaluations. I base my multiples on comparable companies in the market in terms of market cap, portfolio companies, and geography.

For the Public Sector segment, a 15× EBITDA multiple seems reasonable. Best-in-class vertical software companies like Constellation or Topicus often trade at much higher multiples, but they benefit from decades of execution, global scale, and extremely mature operating systems. Chapters’ public-sector portfolio is high quality, but smaller, more regionally concentrated, and still earlier in its scaling journey, which justifies a modest discount.

For the Enterprise segment, I went with a 16× multiple. These are sticky, workflow-embedded software businesses with strong economics, but typically less regulatory lock-in than public-sector assets.

For Financial Technologies, a slightly higher 18× multiple reflects faster growth and strong structural tailwinds from migration and demographics — balanced against higher regulatory and policy sensitivity.

Adding up the segment values, subtracting net debt of roughly €140 million, and adding back the value of the small securities portfolio results in a fair value of about €25.60 per share. At current prices, the stock trades at a premium of roughly 40% to that estimate.

However, you could easily argue for higher multiples, and suddenly, you are in the range where the stock trades today. I really don’t pay that much attention to this “valuation.” But, of course, such a premium makes it difficult to justify a full core position today.

Investment Decision

I believe Chapters Group has everything you need to compound successfully. Capable management, massive, structural tailwinds, a strong shareholder base, and a valuation at 900€ million that leaves plenty of room for compounding.

To me, this fits what Richard Zeckhauser famously called a sidecar investment — an investment where the primary bet is on the people allocating capital. You’re not trying to outsmart them. You’re sitting in the sidecar and benefiting from riding along with exceptional operators.

Warren Buffett did that at Berkshire Hathaway.

Mark Leonard did it at Constellation Software.

And Mitchell Rales did it at Danaher.

It might sound ambitious, maybe even a bit crazy, but it’s at least plausible that Jan-Hendrik Mohr could do something similar at Chapters.

That said, the current share price doesn’t offer a wide margin of safety. The case here is less about statistical cheapness and more about absolute value relative to a very long runway. Given the quality of the shareholder base, including investors like Mitch Rales and William Thorndike, that risk feels acceptable.

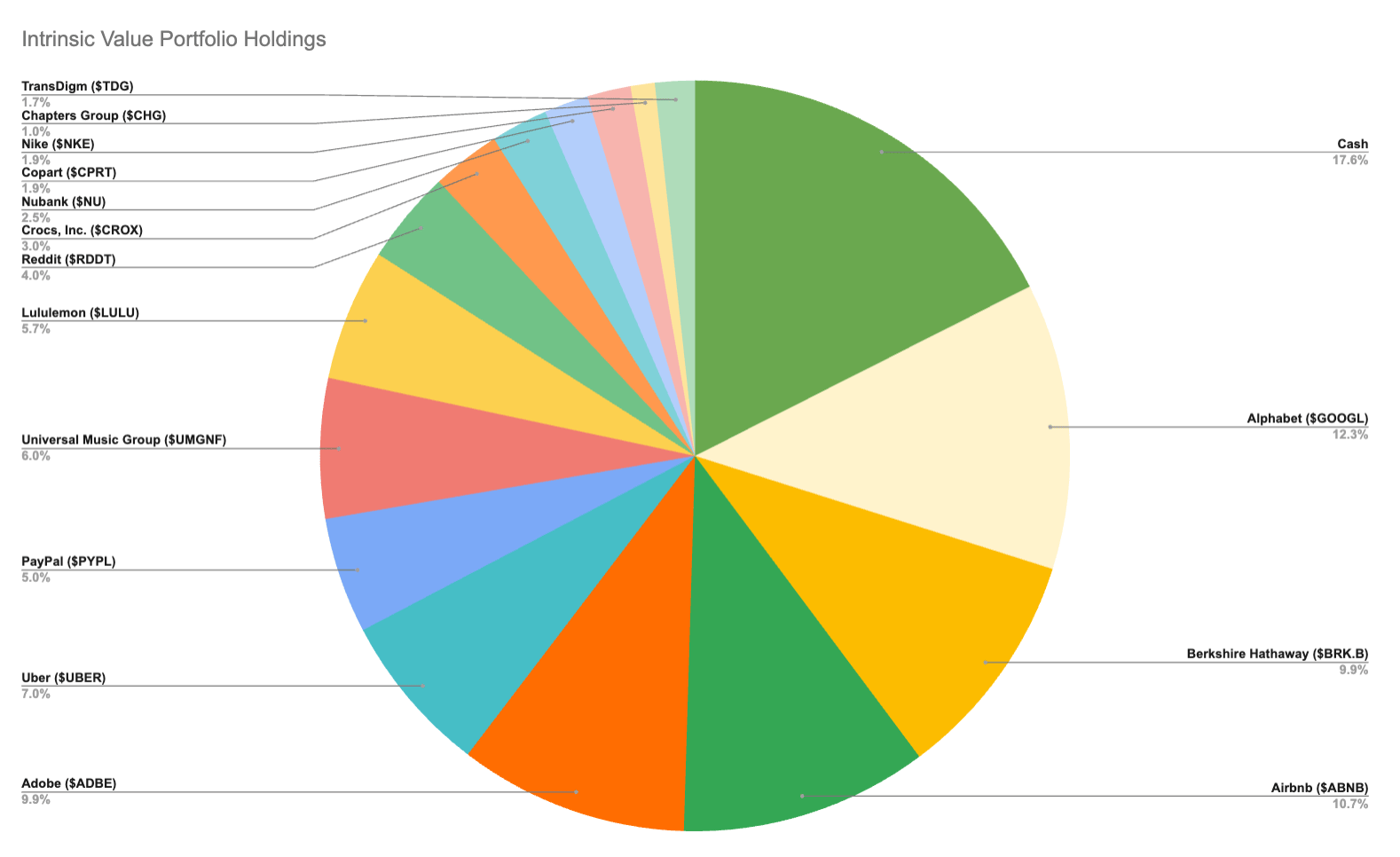

And because relying on “soft factors” alone isn’t how we usually make investment decisions, we’re taking a measured approach. We’ve initiated a tracker position, allocating 1% of the portfolio at a price of 36€. That allows us to follow the story closely. If execution continues to be strong, or if the stock comes under pressure, we can begin building a more meaningful position over time.

For more on Chapters Group, you can listen to our podcast here.

More updates on our Intrinsic Value Portfolio below 👇

Weekly Update: The Intrinsic Value Portfolio

Notes

This week, we decided to add to two existing positions that have come down in recent months and weeks – Uber and Universal Music Group.

Universal Music Group (UMG) — Increased from 4.5% to 6%

Over the past six months, Universal Music Group’s share price declined by roughly 17%, while the core investment thesis remains fully intact.

More music consumption over time should translate into better economics for rights holders, and Universal owns the strongest and deepest music catalogue in the world. The company sits at the center of global streaming growth, pricing power is gradually improving, and the long-term structure of the industry continues to work in Universal’s favor.

What changed is the valuation. Since the IPO, the multiple has compressed significantly — from roughly 50× earnings to around 15× today. It’s trading almost on par with Warner Music Group, which has a significantly weaker catalog.

On top of that, a potential U.S. listing remains an important catalyst on the horizon. Taken together, the risk-reward has improved meaningfully, which is why we used the recent weakness to increase the position to 6%.

Uber (UBER) — Increased from 6.5% to 7%

Uber doesn’t need a lot of arguing, I guess. Nothing about our thesis has changed. Uber continues to execute well, the platform is becoming increasingly profitable, and the long-term operating leverage remains intact. The stock, however, pulled back, and we decided to take advantage of that.

Quote of the Day

"If everything you do needs to work on a three-year time horizon, then you're competing against a lot of people. But if you're willing to invest on a seven-year time horizon, you're now competing against a fraction of those people.”

— Jeff Bezos

What Else We’re Into

📺 WATCH: Clay Finck’s Deep Dive on Mark Leonard and Constellation Software

🎧 LISTEN: William Green interviews Nima Shayegh – Hedge Fund Manager at Rumi Partners

📖 READ: Collection of Shareholder Letters by Mark Leonard

You can also read our archive of past Intrinsic Value breakdowns, in case you’ve missed any, here — we’ve covered companies ranging from Alphabet to Airbnb, AutoZone, Nintendo, John Deere, Coupang, and more!

Do you agree with the decision on CHAPTERS Group?Write a comment to elaborate! |

See you next time!

Enjoy reading this newsletter? Forward it to a friend.

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here.

Join the waitlist for our Intrinsic Value Community of investors

Shawn & Daniel use Fiscal.ai for every company they research — use their referral link to get started with a 15% discount!

Use the promo code STOCKS15 at checkout for 15% off our popular course “How To Get Started With Stocks.”

Follow us on Twitter.

Read our full archive of Intrinsic Value Breakdowns here

Keep an eye on your inbox for our newsletters on Sundays. If you have any feedback for us, simply respond to this email or message [email protected].

What did you think of today's newsletter? |

All the best,

© The Investor's Podcast Network content is for educational purposes only. The calculators, videos, recommendations, and general investment ideas are not to be actioned with real money. Contact a professional and certified financial advisor before making any financial decisions. No one at The Investor's Podcast Network are professional money managers or financial advisors. The Investor’s Podcast Network and parent companies that own The Investor’s Podcast Network are not responsible for financial decisions made from using the materials provided in this email or on the website.