- The Intrinsic Value Newsletter

- Posts

- 🎙️ S&P Global: The Company behind the Stock Market

🎙️ S&P Global: The Company behind the Stock Market

[Just 5 minutes to read]

Every investor eventually faces a simple question:

Do I accept market-like returns, or do I take on the risk of underperforming in pursuit of outperforming?

If you’re reading this newsletter, chances are you’ve chosen the latter — at least to some degree. And when we talk about “the market,” the reference point is almost always the S&P 500, the index built on the largest and most successful companies in the United States.

Even if you benchmark against the MSCI World, you’re still effectively comparing yourself to the S&P 500. Roughly 70% of the MSCI World is made up of S&P 500 constituents.

In other words, there’s no getting around the S&P 500. Today, we’re taking a closer look at the company behind the index — a business that hasn’t just defined the benchmark, but has outperformed it for decades.

Let’s dive into S&P Global and examine whether it deserves a place in the Intrinsic Value Portfolio.

— Daniel

S&P Global: Owning the Market

The Company Behind the Market

S&P Global is best known for the S&P 500 index, and if you are a bit more well-versed in the financial sector, you probably know its Ratings business, too. But the company has a couple of other segments that far fewer investors pay attention to, and they’re every bit as high-quality.

What makes S&P interesting right now, though, is that the stock has pretty much stopped compounding over the last three years. It’s been flat since the 2021 highs, even though the underlying business kept growing steadily. The main reason is valuation. Back in 2021, the stock was simply too expensive, and since then, it has been re-rated back toward more normal levels. Today, it’s roughly in line with its historical valuation — yet sentiment around the stock still feels weaker than you’d expect.

Part of that comes from the usual “AI will destroy every data and software company” narrative. We will get to that.

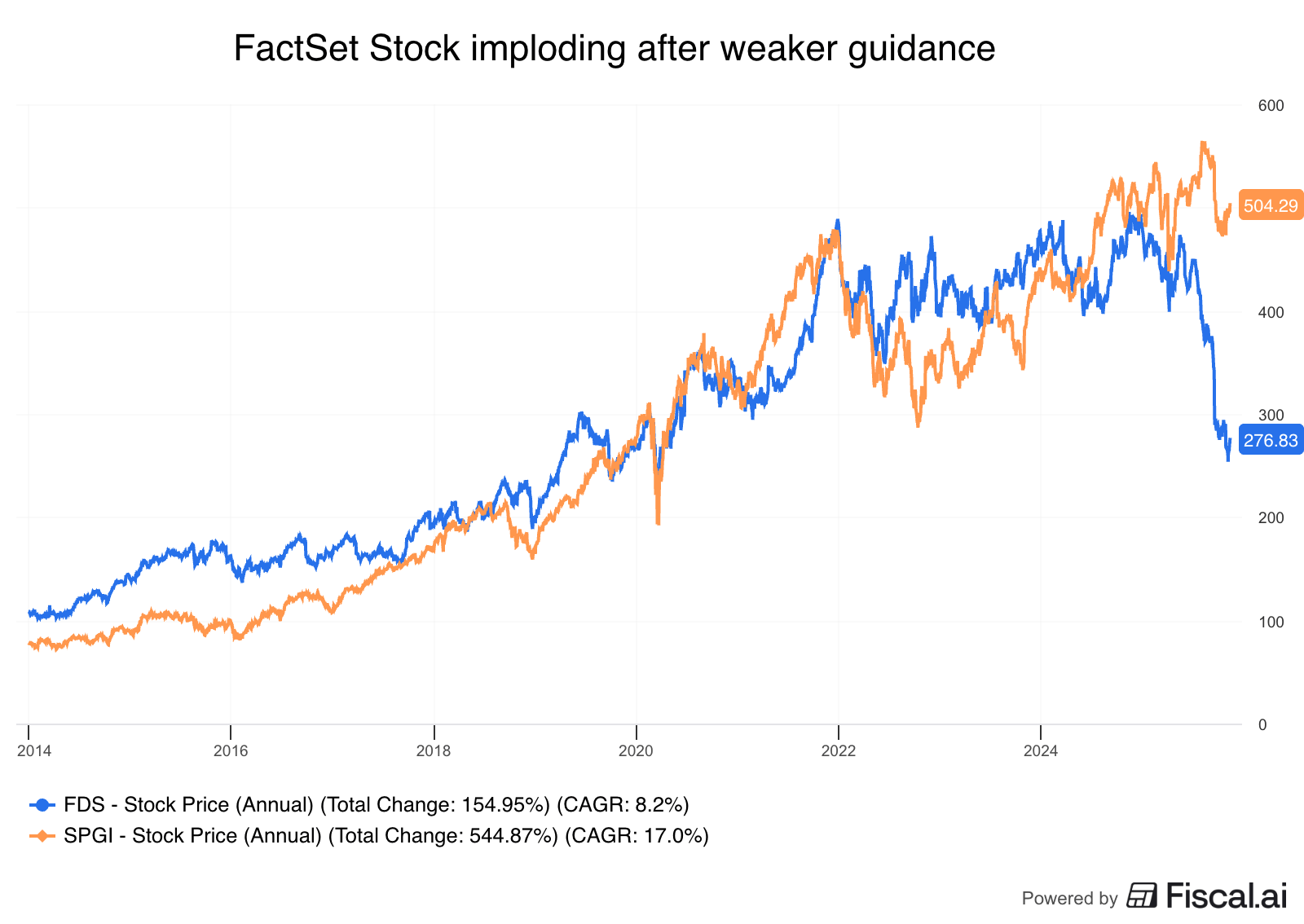

Another reason is that FactSet, one of S&P’s and Bloomberg’s competitors in the financial information market, reported weak guidance, triggering a panic for the sector.

All of this pushed S&P down despite very little actually changing in the underlying business. So the question becomes: Is this a rare chance to buy a world-class compounder at a discount?

The Ratings Business

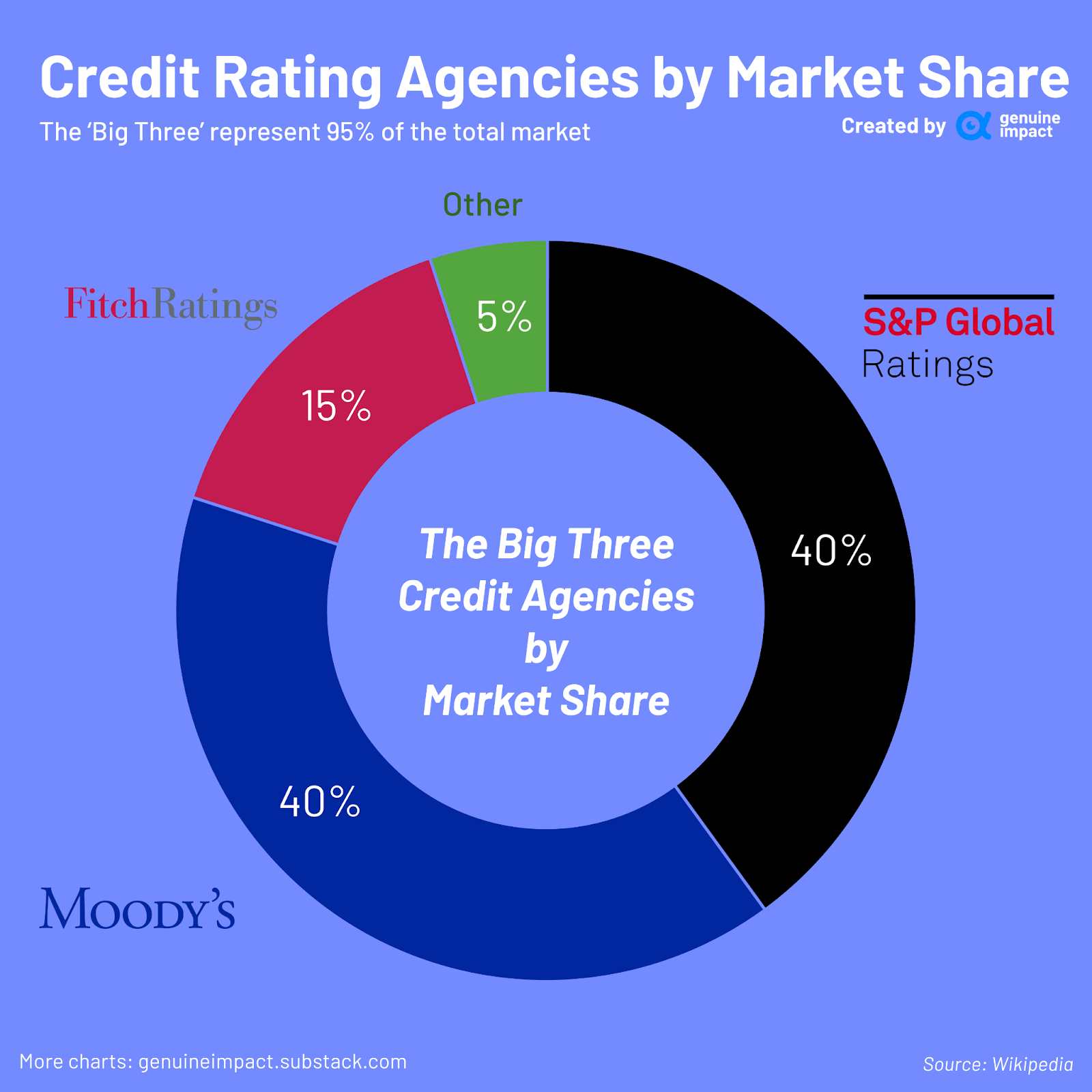

S&P Ratings is the largest credit-rating agency in the world, operating in a tight regulatory oligopoly alongside Moody’s and Fitch. Together, the big three control about 95% of the global ratings market, and S&P alone accounts for roughly 40%.

Whenever a company or government wants to issue debt, whether that’s a corporate bond, a leveraged loan, or a sovereign note, they need a rating. Many institutional investors, including pension funds, insurers, and some mutual funds, are legally prohibited from buying securities that aren’t rated by an NRSRO, a Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organization. Quite the tongue twister…

That designation is granted by regulators and, realistically, new entrants almost never receive it. It’s a system that has effectively entrenched the existing big three for decades.

In our TransDigm episode a couple of weeks ago, we discussed the differences between natural monopolies and government-granted monopolies. TransDigm was a mix of both, and I’d say it’s the same with S&P. Perhaps the Ratings business is tilted more toward a government-granted one, but there are market-driven advantages as well.

Even without regulation, markets would still converge on the same trusted providers. Ratings only work if investors believe in them, and belief comes from decades of default data, deeply studied methodologies, and global consistency.

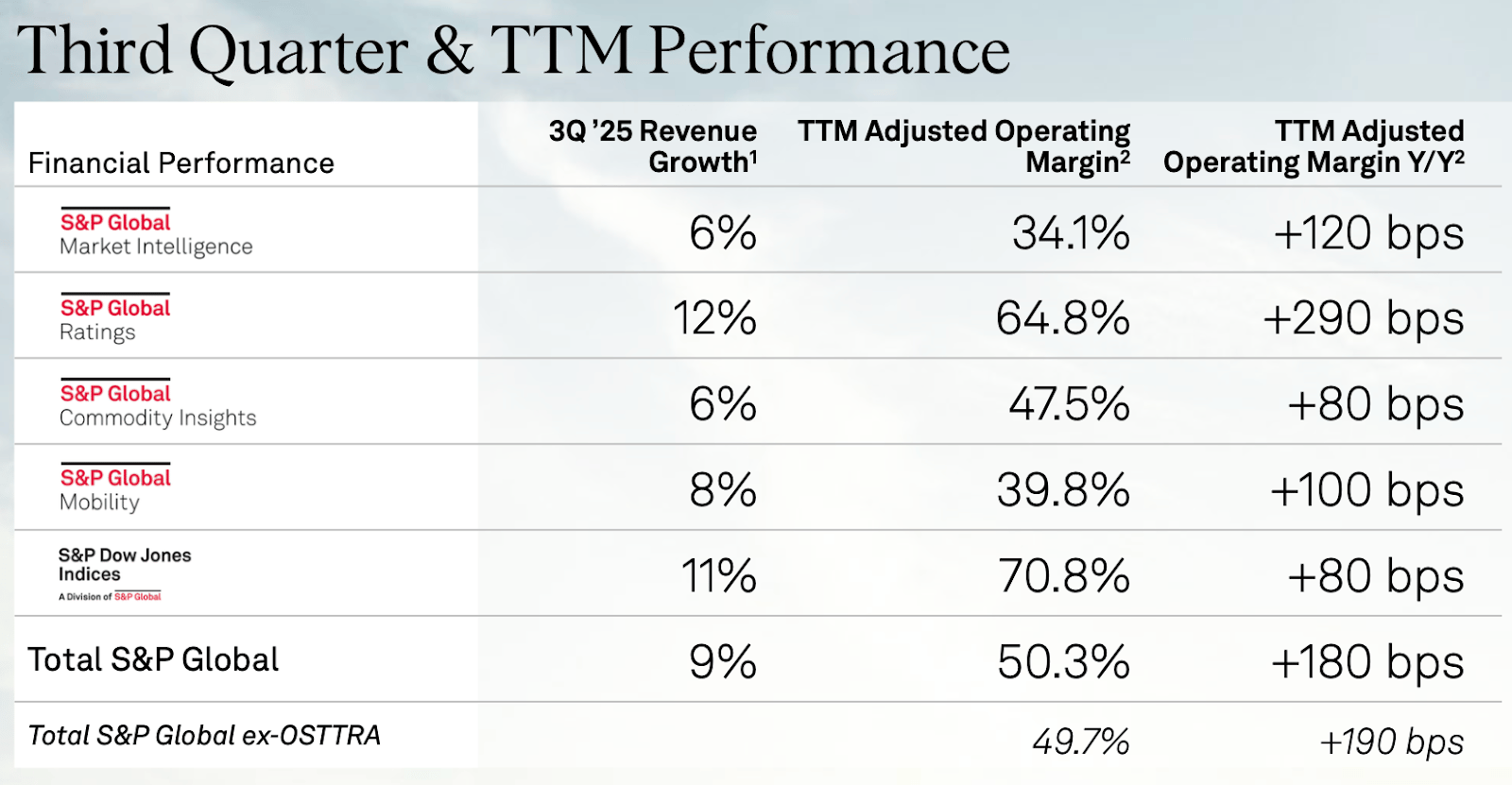

All of this translates into a business with enormous pricing power and extremely high margins. Ratings run at operating margins above 60%, making it one of the most profitable segments within S&P Global, and this is inside a company where even the “low-margin” businesses operate around 40%.

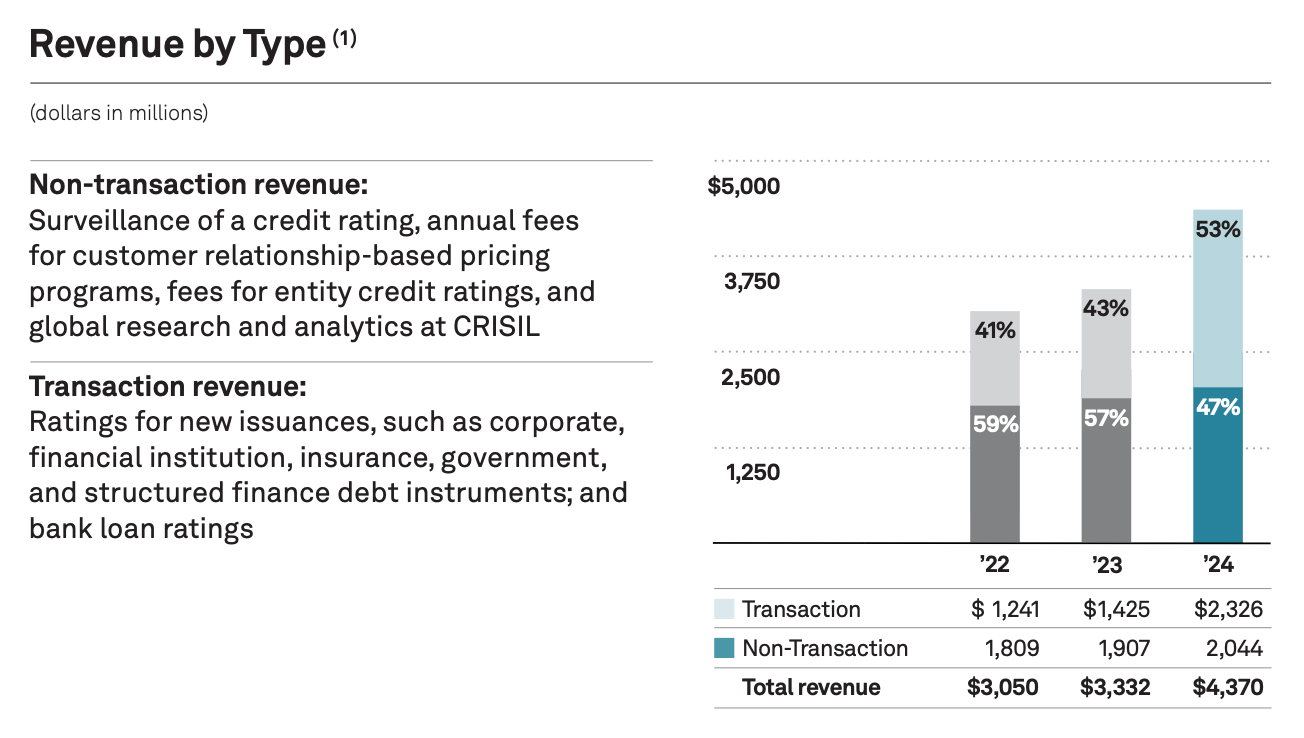

If anything, the Ratings Business is the most cyclical since a large chunk of its revenue is transactional. When new debt is issued, S&P makes money, but it’s not a subscription-like business like some of the other segments. That makes the business quite cyclical. When interest rates are high, debt issuance slows down, and demand for ratings is low.

When rates fall, however, issuance rebounds and Ratings revenues accelerate. In 2024, Ratings grew more than 40% year-over-year as companies rushed back into the debt markets to refinance and lock in lower costs. Ratings is incredibly sensitive to the direction of interest rates — and with cuts expected, the setup looks especially favorable.

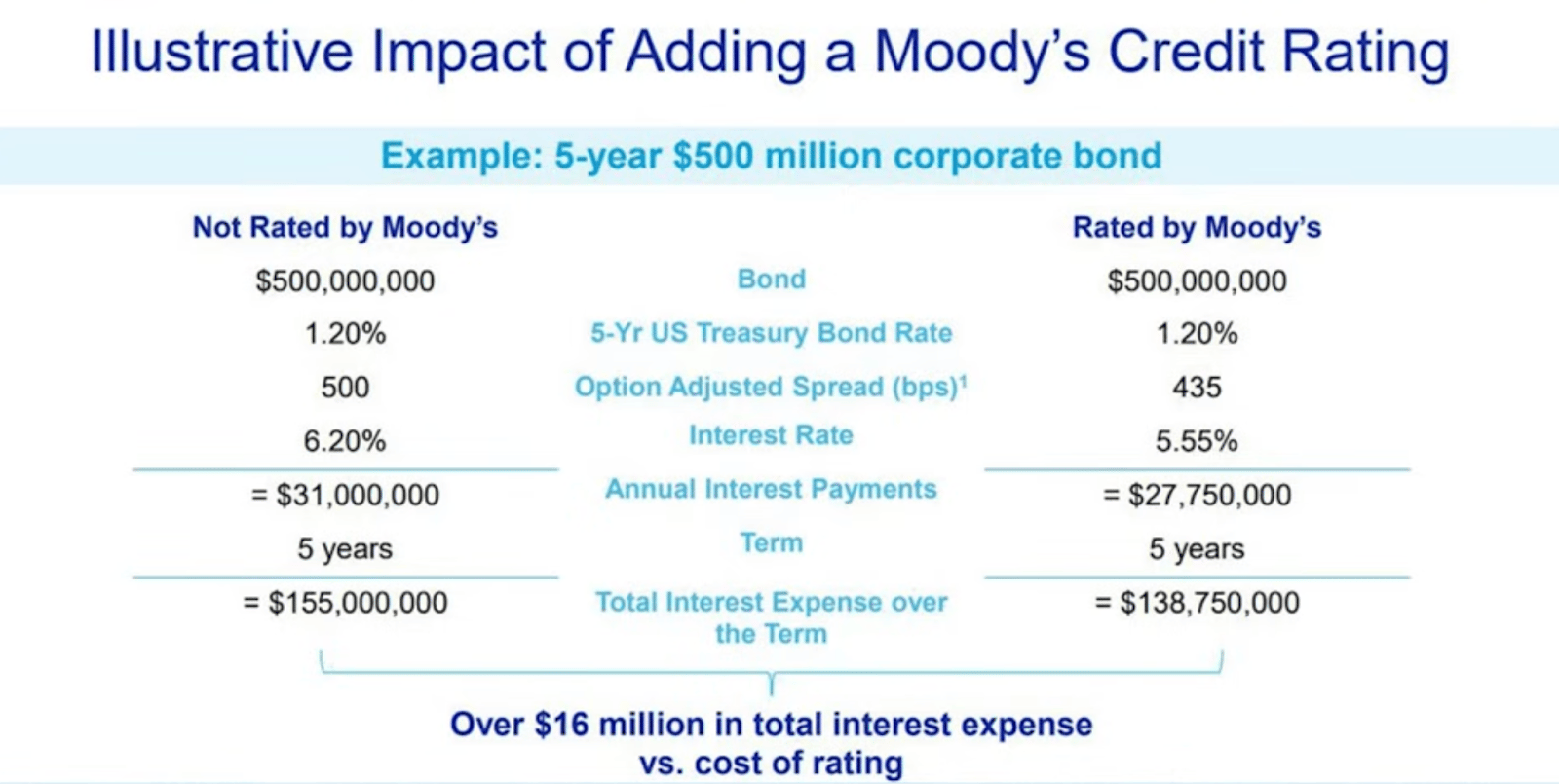

Coming back to the idea of the natural moat for a moment: even if a new competitor tried to undercut S&P with dramatically cheaper ratings, companies would still choose to pay S&P. That’s because a rating from a lesser-known agency often results in higher borrowing costs, sometimes millions more per year in interest. So paying S&P a few hundred thousand dollars for a rating can easily save a company ten times that amount in interest over the life of a bond. It would be irrational not to use S&P.

The example above features a Moody’s rating. Moody’s is the next-biggest rating agency and one of Buffett’s core holdings. When Buffett explains the moat of the Ratings business, he keeps it relatively simple:

“Some parts of the world feel they need rating agencies.”

S&P has also done an impressive job smoothing out the natural volatility of the Ratings business by building a large recurring-revenue base through so-called surveillance fees. After the initial rating is issued, companies and governments pay S&P every single year to maintain, monitor, and update that rating. This ongoing surveillance involves regular model updates, financial statement reviews, meetings with management teams, and the publication of revised assessments if anything materially changes.

This turns every issued rating into a multi-year revenue stream that continues to pay even when new bond issuance dries up. It’s also a good way to retain customers. So while the transactional side of Ratings surges during periods of low interest rates and falls when borrowing slows, the surveillance side continues almost unaffected.

In years when new issuance is low, these surveillance fees (non-transactional revenue) can account for up to 60% of revenue. In times of higher issuance, it’s about 45%-50%.

The Market Intelligence Business

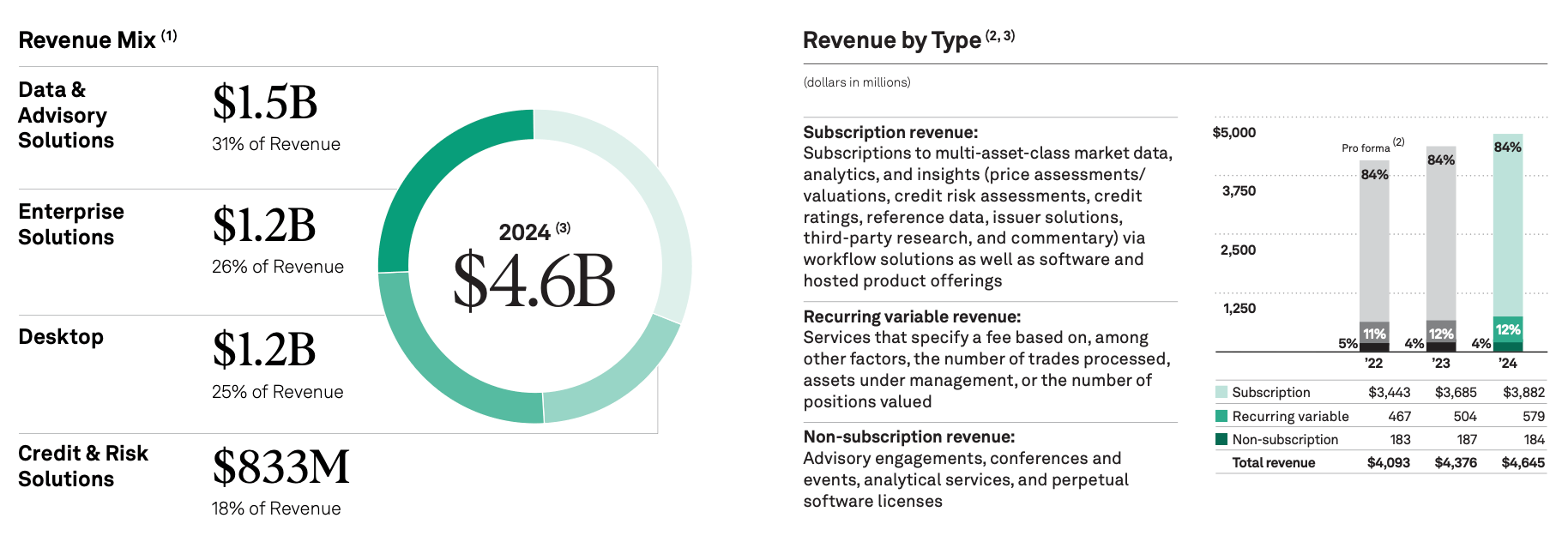

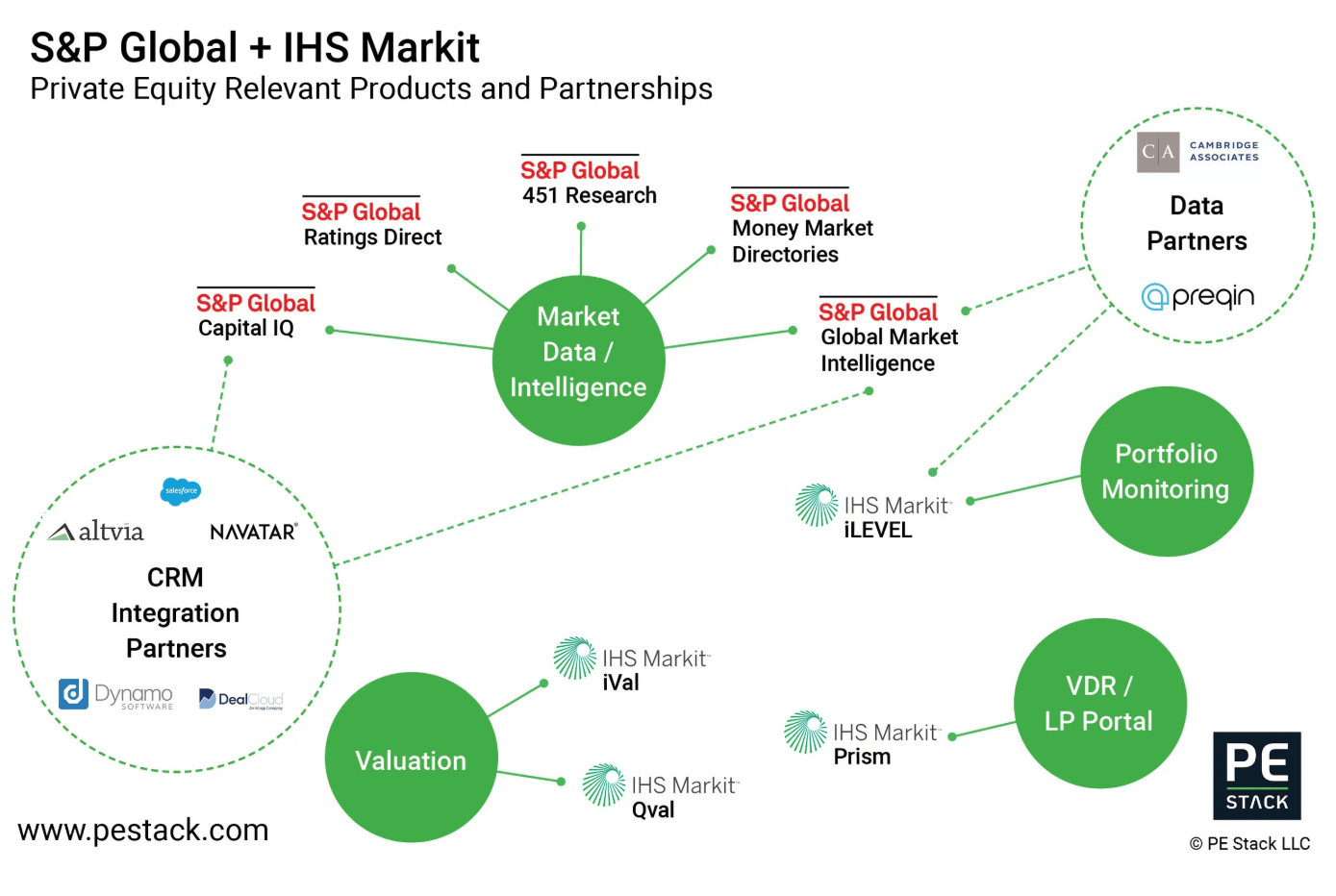

The next major piece of S&P Global is its Market Intelligence division, which most people know through one product: Capital IQ. It’s essentially S&P’s equivalent of the Bloomberg Terminal or FactSet, but with a slightly different profile.

Bloomberg still dominates in real-time market data and carries that prestige factor on trading floors. I joked about it in the podcast, but the iconic black-and-orange screen is somewhat of a status symbol in the financial world. With $30,000/year, Bloomberg isn’t cheap either.

FactSet is cheaper at around $12,000/year and is predominantly used by asset managers. Capital IQ is built to be the platform that ties everything together — company financials, ownership structures, industry datasets, private market information, credit data, regulatory filings, and a lot more than most investors realize exists.

S&P leverages all the data it has from the different business segments and combines them in Capital IQ. That’s the unique value proposition that makes it a sticky business despite the competition in the space.

Roughly 84% of the revenue here comes from long-term subscriptions, and another chunk comes from recurring usage-based fees.

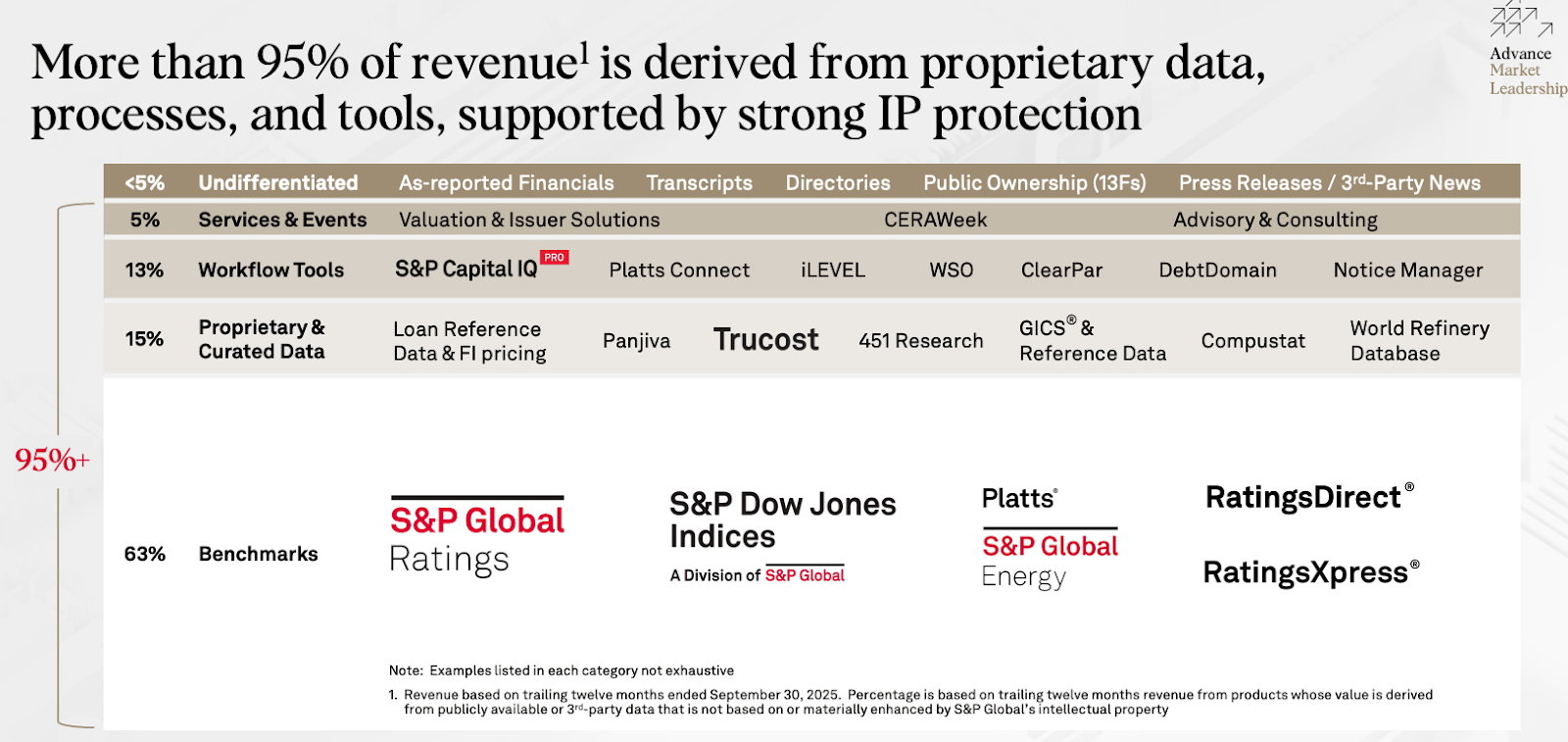

According to S&P, more than 95% of the Market Intelligence dataset is proprietary. That’s a crucial point because, you guessed it, the market is seeing this part of the business under threat from AI.

Literally ten minutes ago, I came across this post on X:

What doesn’t help with the narrative is that FactSet cut its guidance earlier this year and blamed slower sales cycles and longer approval processes. The market basically rang the alarm bell for the entire data industry. FactSet fell nearly 45%, which is almost as much as during the Financial Crisis. And even though S&P Global wasn’t affected operationally, its stock still got pulled down by association.

It might come as a surprise to you after already hearing our takes on Adobe or Salesforce, but we believe that AI will not be the end of S&P’s Market Intelligence segment or S&P in general. The data that powers Market Intelligence is not something AI can scrape off the internet.

I spend dozens of hours a week working with ChatGPT, Gemini, and other AI tools when researching companies. And I’m aware that they will only get better, but they do not have the access of a Bloomberg or Capital IQ, and the level of information is far inferior.

You need decades of curated, cleaned, and legally licensed datasets — and S&P is one of the few companies in the world that has them. The real risk, if anything, is that investment banks, asset managers, and corporate finance teams automate more of their entry-level analytical work with AI.

If that’s the case, they might eventually need fewer analyst seats and, therefore, fewer Capital IQ licenses. But even that risk is somewhat balanced out by the efficiency gains S&P can generate internally. The company owns Kensho, an AI subsidiary that has been building machine learning tools for years, and S&P is already integrating generative AI directly into Capital IQ — allowing users to summarize earnings calls, generate peer comparisons, or identify anomalies in seconds.

In short, I’m very skeptical that AI will replace the need for tools like Bloomberg and Capital IQ. Again, the customer is not you and me. We are talking about the biggest financial players in the world. They need reliable data, and they need it fast. AI will forever change the industry and the tools, but as long as S&P owns the data, I have a hard time believing it will disrupt S&P.

The Index Business

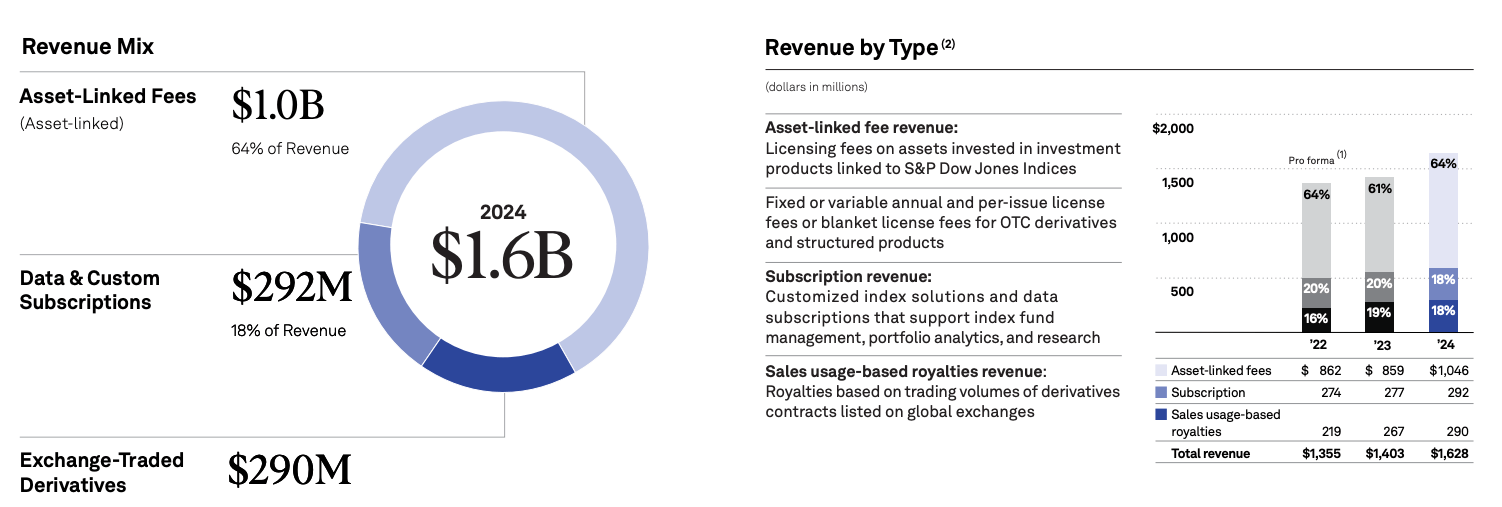

Getting to the part that most people know best — the Index business. Despite being one of the most recognizable pieces of S&P Global, it actually makes up only about 10% of total revenue. What it does contribute, unsurprisingly, is a lot of profit. The margins here are so high that its share of earnings is roughly double its share of revenue.

I won’t go into too much detail here, partly because I don’t want this article to turn into a small book, and partly because we already did a deep dive into the index business in our MSCI podcast and newsletter.

At its core, S&P builds benchmarks — not just the S&P 500, but thousands of others across equities, fixed income, commodities, factors, ESG screens, and volatility. Asset managers like BlackRock and Vanguard then license those benchmarks to build ETFs and mutual funds. The licensing fee S&P earns is usually just a few basis points, which looks tiny in isolation. But when trillions of dollars track those benchmarks, those basis points turn into an astonishing amount of high-margin revenue.

The shift from active to passive investing has been one of the strongest megatrends of the past two decades. Every time a dollar flows into a passive S&P 500 ETF, whether it’s through a 401(k), a brokerage account, or a robo-advisor, S&P Global earns a royalty. And even now, when I talk to friends and family, I can’t help but think that we are still early.

Sure, most people have heard of ETFs by now, and for many, it's become part of their portfolio, but it feels like Shawn and my generation will invest far more in ETFs than our parents’ generation. And those portfolios will grow significantly over the coming decades.

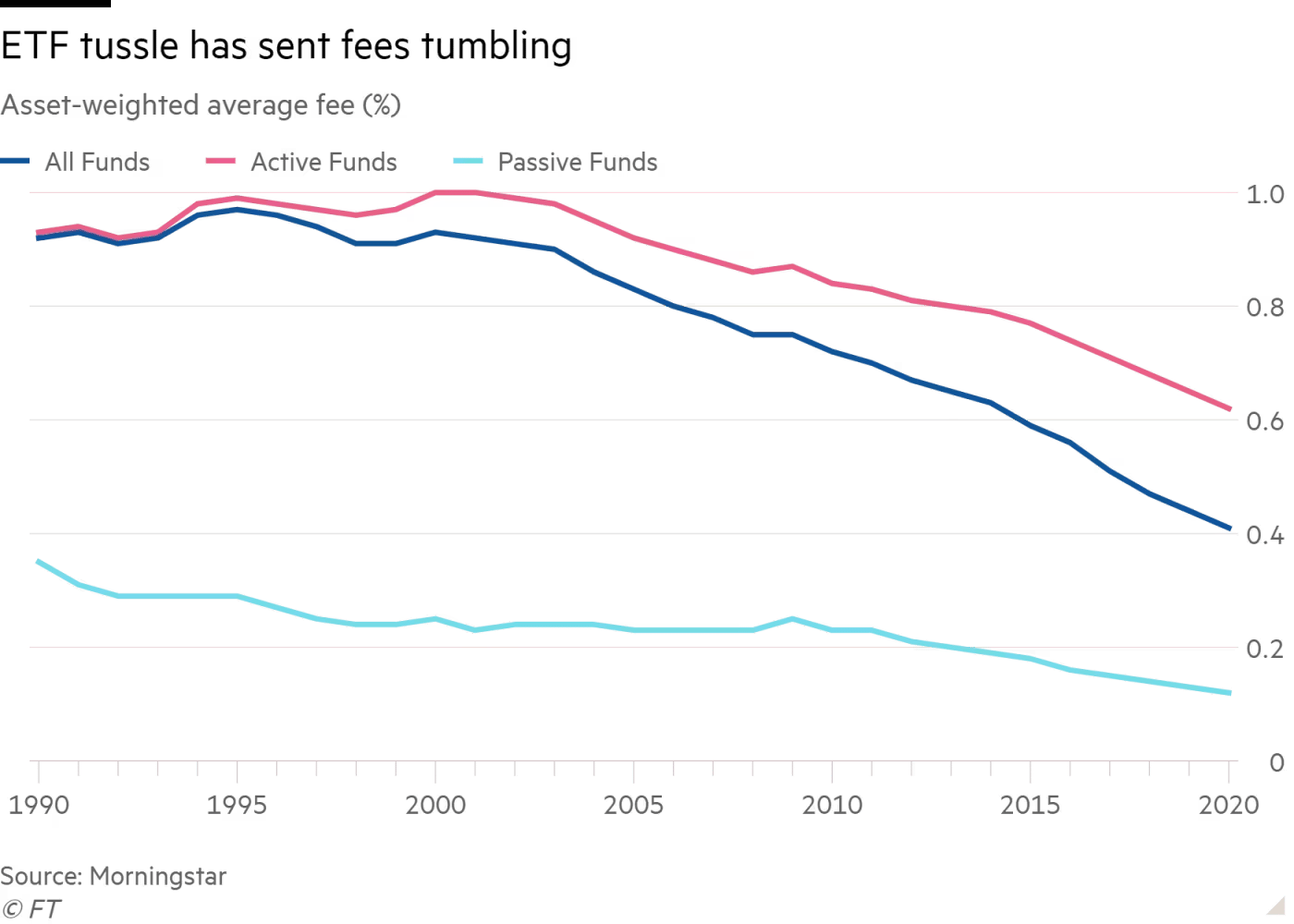

Of course, nothing in this business is risk-free, and the biggest concern is fee compression. Management fees on many index funds have fallen dramatically, with some products now priced essentially at zero. Asset managers have figured out that ultra-low-fee index funds are a great way to pull customers into their ecosystem, with the hope of monetizing them through advice, brokerage, or other services. If that trend continues to accelerate, S&P and MSCI could eventually face more serious pressure on their royalty rates as well.

Another potential risk worth mentioning is the rise of direct indexing. Instead of buying a fund, investors (or robo-advisors) construct the index themselves by buying all the underlying stocks directly. They can avoid companies they don’t want, harvest tax losses more efficiently, or create custom tilts.

I know that sounds innovative and somewhat inevitable, but honestly, I believe this might end up being a niche product relative to broad passive investing. The whole point of ETFs is to invest and forget.

And perhaps more importantly, even in a direct indexing world, platforms like Schwab or Morgan Stanley still need a benchmark to determine which stocks go into the custom portfolio. And that benchmark doesn’t magically appear out of thin air — it still has to be licensed… from S&P.

The Commodity Insights Business

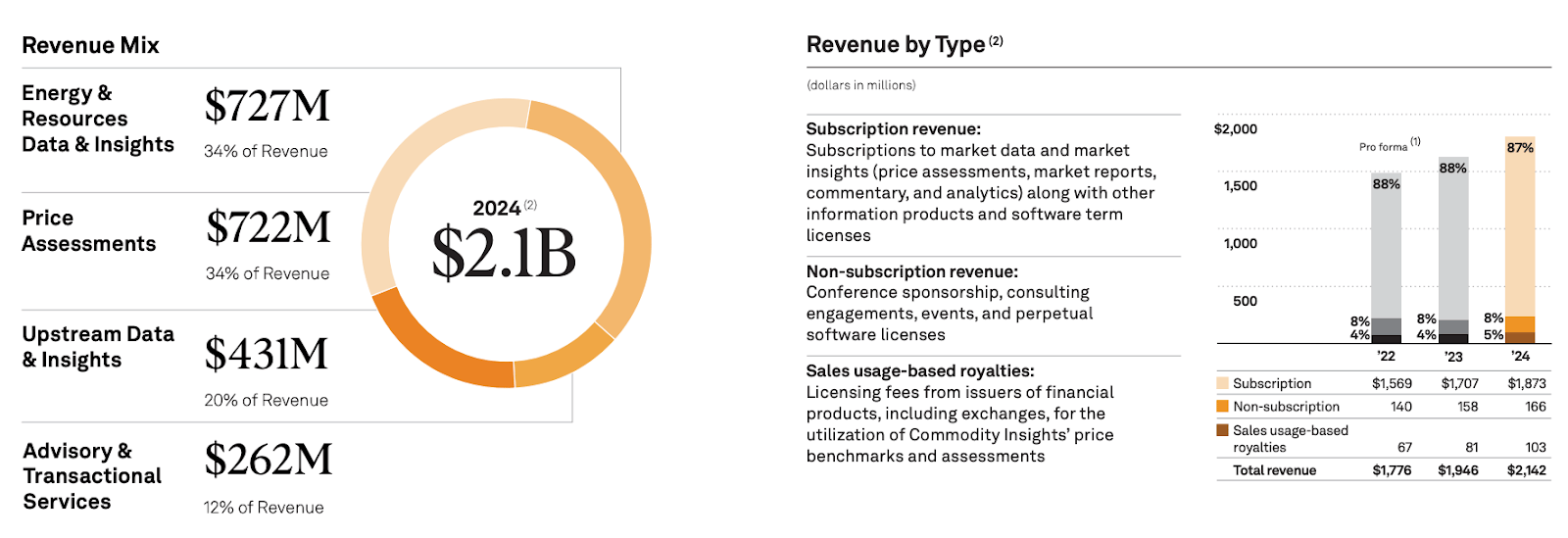

Another part of S&P Global, and one that often flies under the radar, is its Commodity Insights division — formerly known as Platts. And even though commodities are among the most volatile markets on the planet, S&P has managed to turn this business into a remarkably steady, subscription-heavy operation. Nearly 90% of its revenue comes from annual or multi-year contracts, and the products are so deeply embedded in global energy and materials markets that replacing them would be close to impossible.

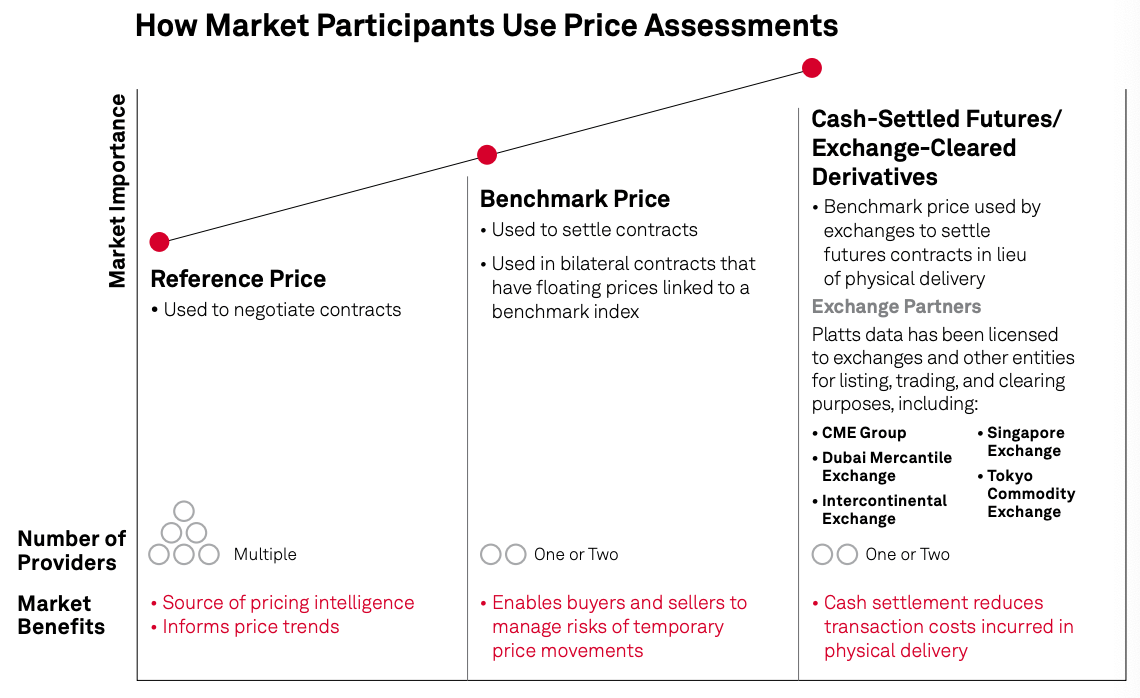

The core of the business is its benchmark pricing. When an oil trader signs a contract that says “Brent Platts + $0.50,” that “Platts” reference comes directly from S&P Global. Of course, S&P doesn’t set those prices itself; it gathers thousands of bids, offers, and completed trades from market participants, verifies them, and publishes standardized benchmark assessments that the entire industry agrees to use.

Those numbers show up everywhere — in physical contracts, derivative markets, risk models, and even government regulations. And once a benchmark like that becomes entrenched, switching away from it would require every major counterparty, regulator, and exchange to agree at the same time. As you can imagine, that almost never happens.

In fact, looking at S&P’s businesses, I think the Commodity business is high up the list of the highest-moat businesses. Physical commodities are incredibly complex. A single oil shipment can differ by grade, sulfur content, delivery window, credit terms — the list goes on.

Even if all trade data magically became public tomorrow, someone would still need to interpret it, normalize it, and decide what counts as the representative market price. That’s exactly the expertise S&P provides.

The Mobility Business

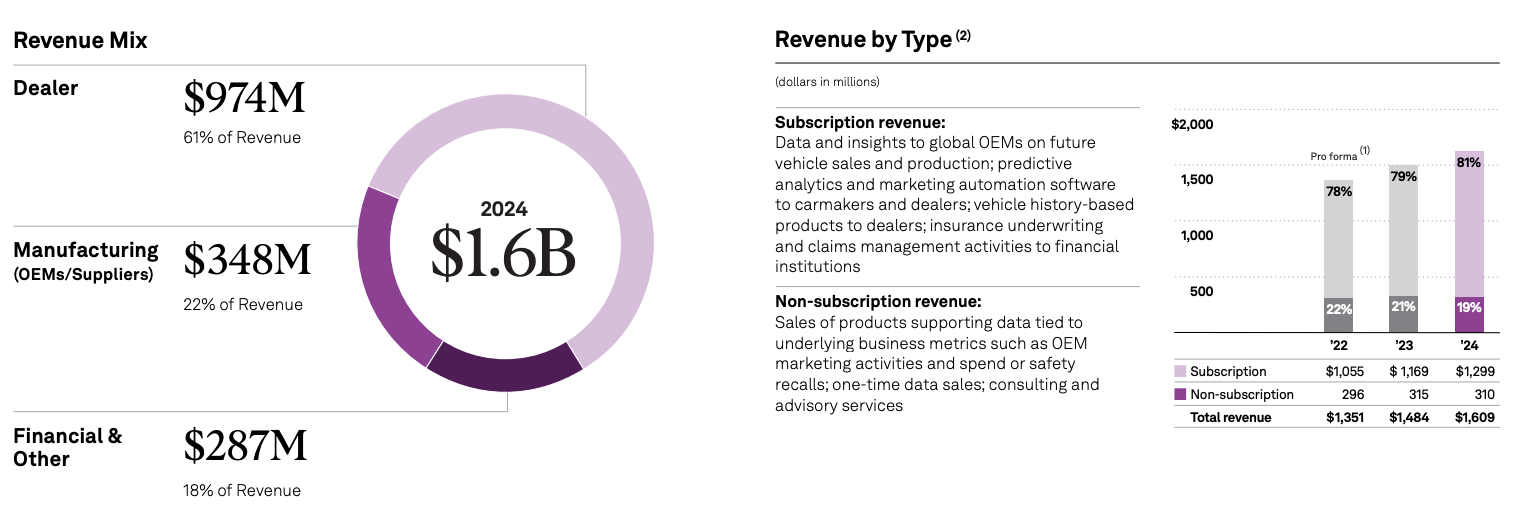

The Mobility segment is probably the most unknown part of S&P Global’s portfolio, largely because it has very little to do with financial markets at all. It came over through the IHS Markit acquisition and is built around one of the most comprehensive automotive data ecosystems in the world.

That includes decades of production forecasts, supply-chain intelligence, and, most notably, the massive Carfax database, which tracks vehicle ownership and maintenance histories across North America.

The quality and scale of this data make it incredibly difficult to replicate. Virtually every major automaker, dealer network, insurer, and lender relies on these datasets to understand demand trends, manage inventories, price risk, and evaluate used vehicles.

But despite its strengths, the Mobility segment is not a perfect fit for S&P Global’s broader focus on financial market infrastructure. The division serves a different set of customers and doesn’t benefit from the same ecosystem synergies that link Ratings, Indices, Market Intelligence, and Commodity Insights.

So S&P has decided to spin it off. Management announced the plan earlier this year, expecting that a standalone Mobility company could unlock greater value and operate with greater strategic focus.

Analysts estimate the unit could be valued between $10 and $12 billion, and S&P shareholders would receive shares in the new company once the separation is complete.

Financials & Capital Allocation

That was a lot, I know. But I think it’s important to learn about all parts of the business, because they all materially contribute to the overall business. And that diversification is also part of why I prefer it over SMCI in the long run.

Anyway, having looked at all the segments in isolation, how about we put it all together? Over the last decade, S&P Global has grown revenue at roughly 10% per year, operating profit around 15%, and earnings per share right in that same range.

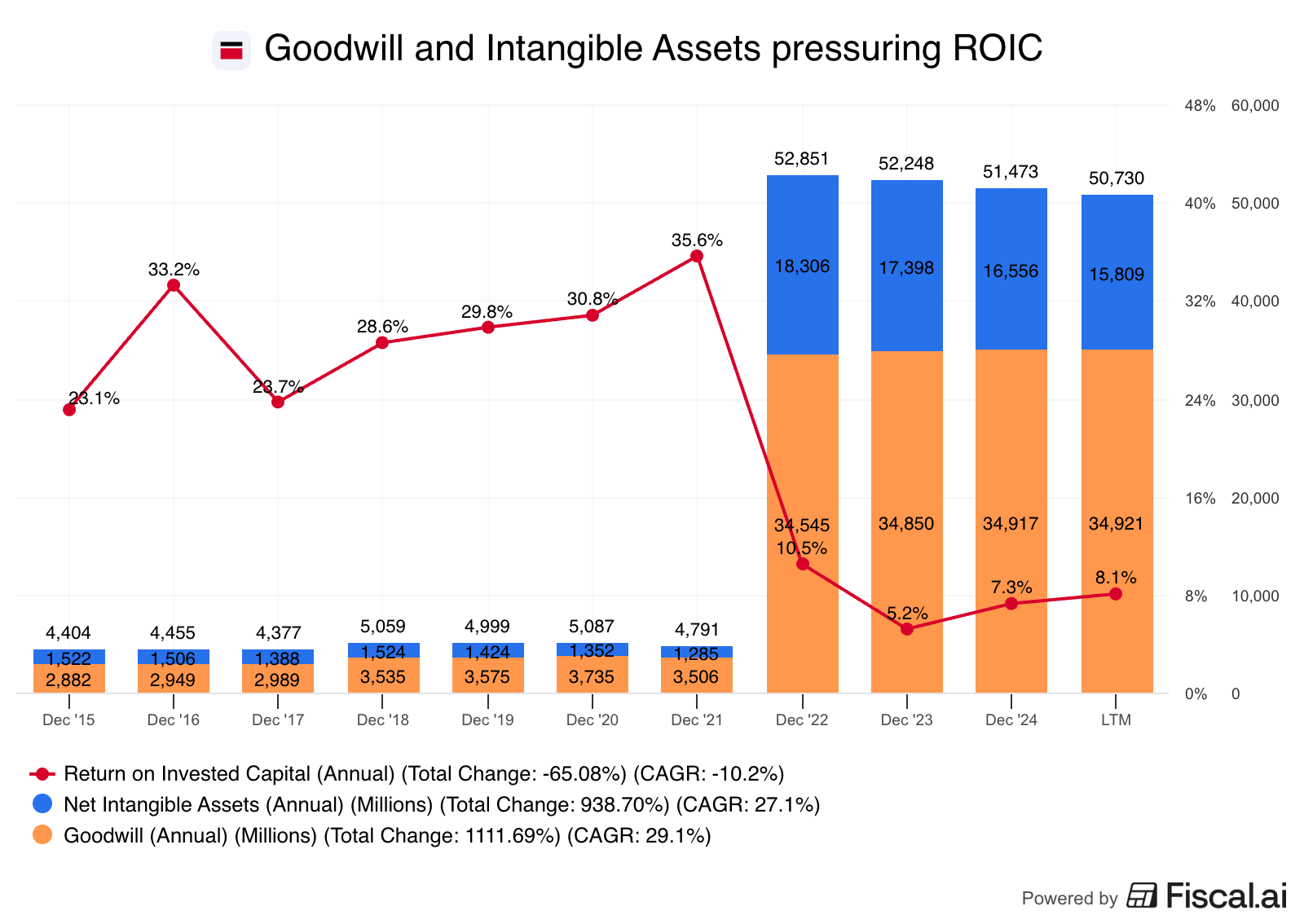

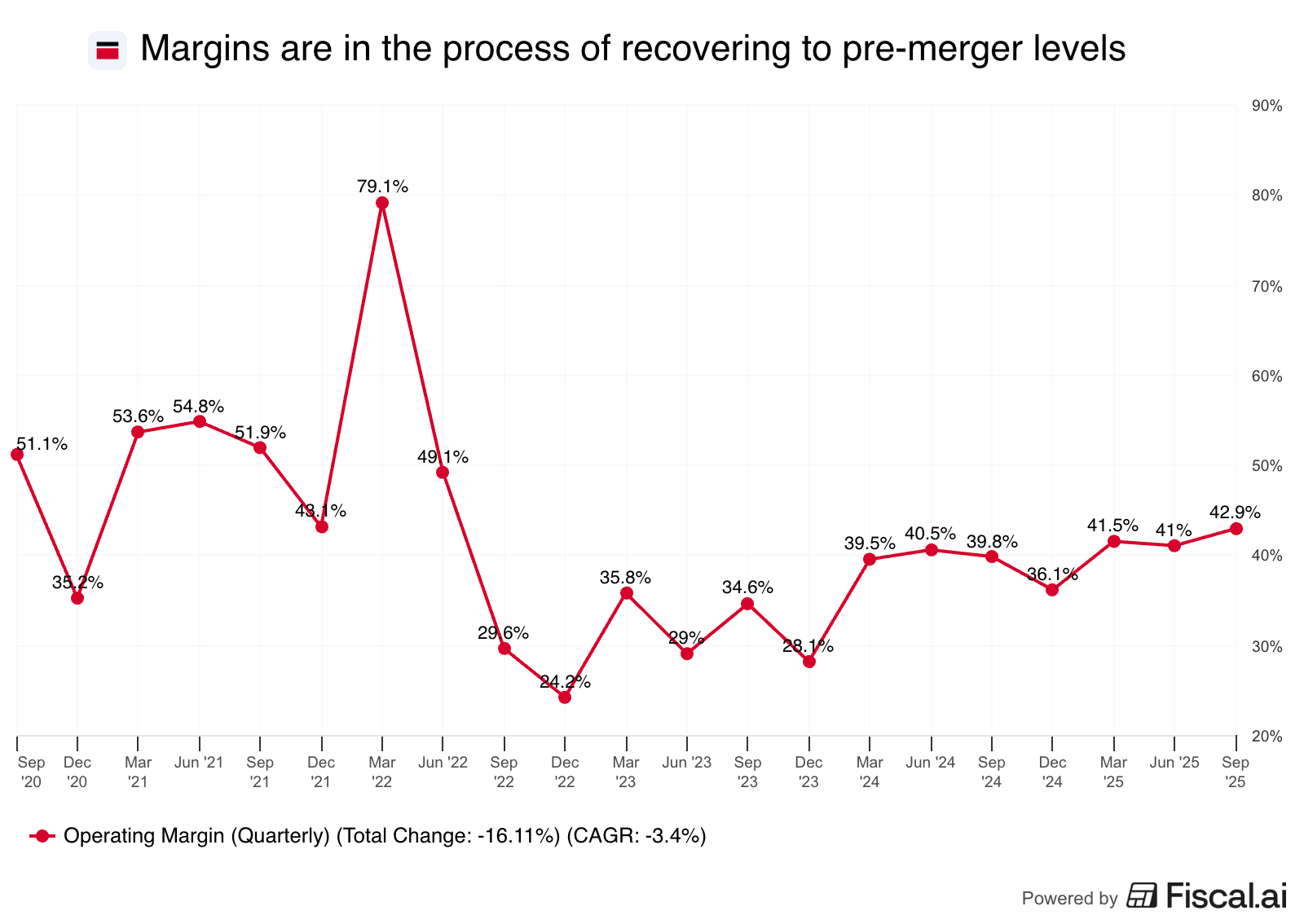

The IHS Markit acquisition in 2022 did put some pressure on EPS growth, though, mainly because it inflated the share count. Before that deal, S&P had been steadily reducing its shares outstanding by about 2% a year. Then the merger added more than 120 million new shares, taking the total from roughly 240 million to around 360 million. Management responded quickly and ramped up buybacks, bringing the count down to roughly 320 million by the end of 2022 — but you can still see the dilution in the long-term EPS trend.

The acquisition also had a noticeable effect on S&P’s return metrics. ROIC, which used to sit comfortably in the high-20s to mid-30s, dropped into the high single digits after the deal closed. Of course, the underlying company didn’t get worse, but the balance sheet suddenly carried a massive amount of goodwill and intangible assets.

And when the denominator of the ROIC equation balloons overnight, the ratio looks weaker, even if the underlying operations remain just as profitable as before. If you adjust for goodwill, ROIC is still well into the 20% range.

Margins tell a similar story. Across all five segments, S&P operates around 40% at the operating line, which is already phenomenal and puts it in the same league as companies like Microsoft. But before the IHS merger, those margins were even higher, around 55%. The IHS businesses are structurally lower margin, so we’re unlikely to see those old peaks again anytime soon. Still, management believes S&P can push back above 50% over the next few years as synergies continue to kick in and the company benefits from more operating leverage at scale. Gross margins hover around 70%, once again right in line with some of the best software businesses in the world.

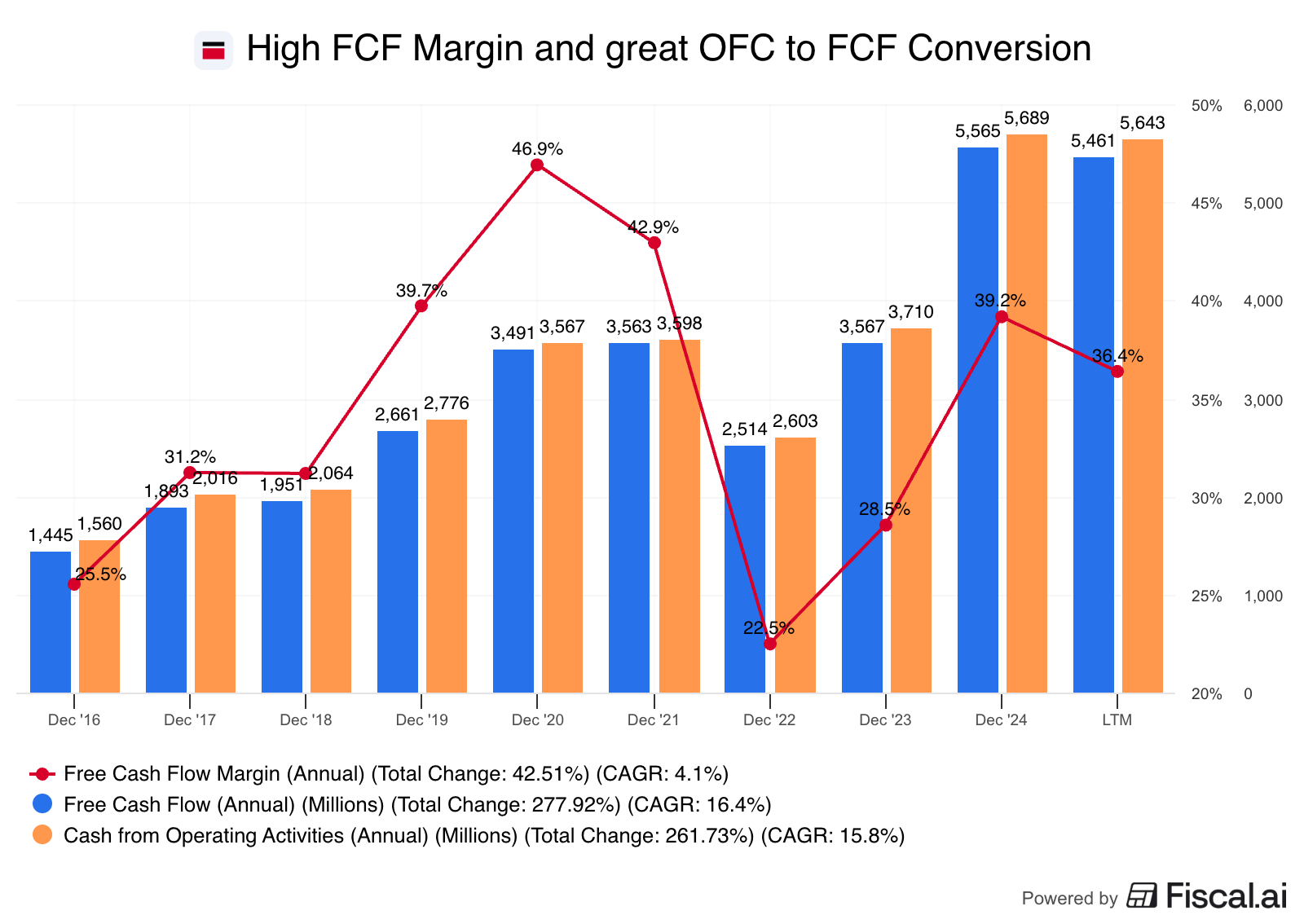

But the metric where S&P really stands out, even compared to Microsoft, is free cash flow margin. Microsoft sits at roughly 26%, while S&P is a full ten percentage points higher, consistently landing in the mid-30s. A big reason for that is capex. S&P’s capital expenditures usually come in well below 2% of revenue, which means almost every dollar of operating profit turns straight into cash.

That leaves plenty of room to return cash to shareholders. Excluding the IHS Markit dilution, S&P has reduced its share count by about 20% since 2012 and has increased its dividend by an average of 10% per year for 51 consecutive years. It’s one of the longest dividend-growth streaks in the market, even if the yield, currently around 0.8%, doesn’t look particularly exciting. That’s the downside of owning a stock that compounded at even higher levels.

Looking forward, buybacks will likely remain the main tool of value creation. Management hasn’t committed to a new buyback program, but they’ve repeatedly said they aim to return 85% of free cash flow to shareholders each year. Assuming around $5 billion in annual FCF and roughly $1.2 billion in dividends, that leaves just over $3 billion for buybacks — roughly 2% of the current market cap, which should support steady per-share growth.

Management and Incentives

One noteworthy change at S&P Global over the past year has been the transition in leadership. The company appointed a new CEO, Martina Cheung, who previously ran the Ratings division.

As is often the case with internal hires, it’s unlikely we will see any major changes under her leadership. If anything, the business might become even more focused on its core strengths. The decision to move ahead with the spin-off of the Mobility division, for example, happened under her watch.

What’s still a bit of a turnoff is the low level of insider ownership and the somewhat underwhelming incentive program. But to be fair, it’s hard for any non-founder executive to build a meaningful personal stake in a $150 billion company, so it’s not entirely surprising.

As for compensation, annual bonuses are tied to revenue and margin targets, while stock grants are primarily linked to EPS growth. It’s not a bad setup by any means, but it’s also not the strongest we’ve seen. The good news is that it has worked for S&P for decades, and there’s really no reason to believe it won’t continue working going forward.

Valuation and Investment Decision

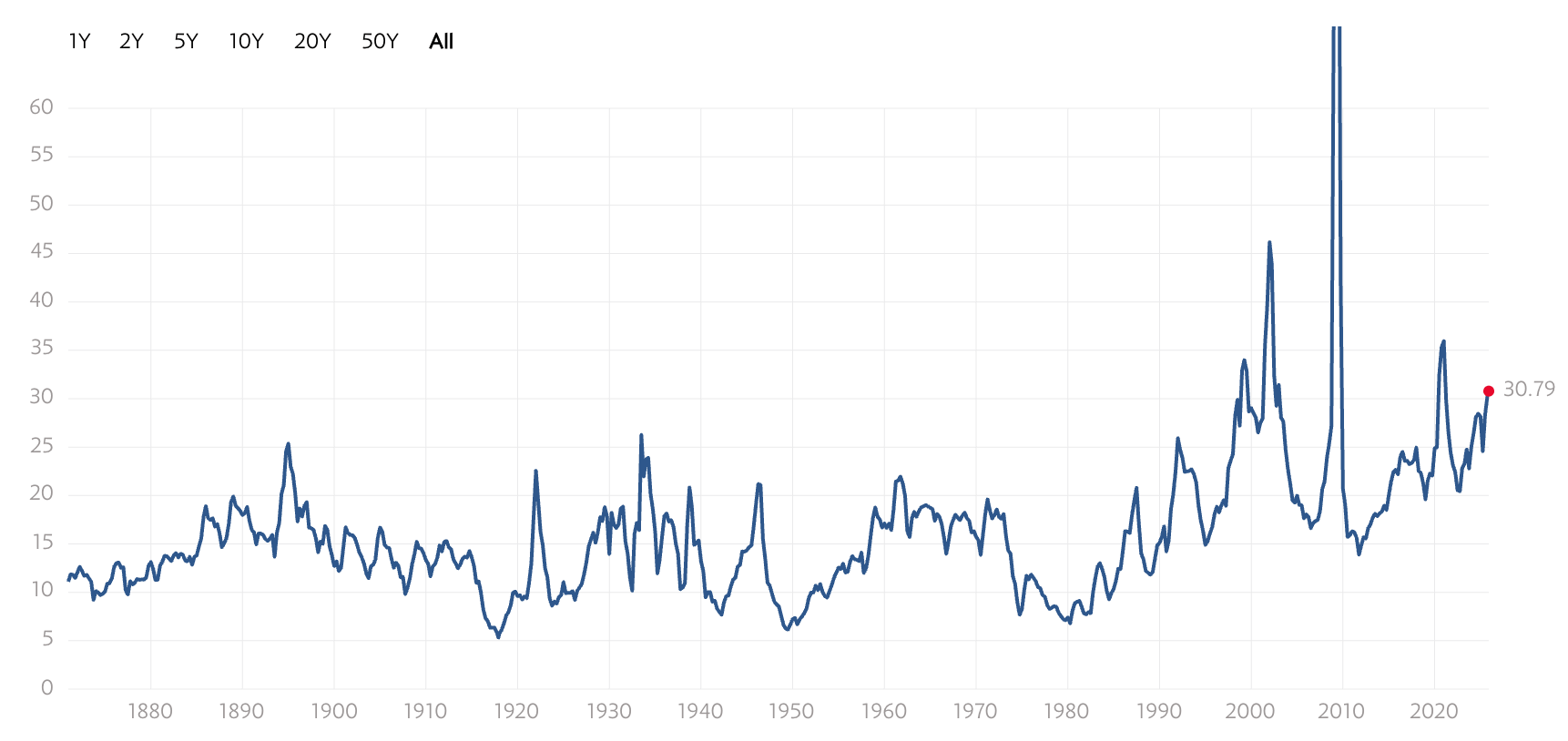

Shawn and I recently talked about the valuation of the overall market. The S&P 500 is currently trading at around 30 times earnings — roughly double its historical average. I’m a bit hesitant to call the market massively overpriced based on that data point alone. Part of the truth is that the average company in the S&P 500 today is a much better business than it was in 1960.

But even with that in mind, I’m still not entirely comfortable underwriting a 30x multiple. So when I tell you that S&P Global looks “cheap” relative to the market — simply because it trades at roughly the same multiple while being, without question, a far better business than the average S&P 500 company — take that with a grain of salt. That’s the kind of relative valuation that gets you in trouble in bear markets.

Valuation eventually catches up with every company, no matter how good it is. Back in 2021, S&P Global was trading at a P/E north of 40x. Since then, the stock has gone basically nowhere, zero returns over the last three years, and plenty of other high-quality names have run into the exact same problem.

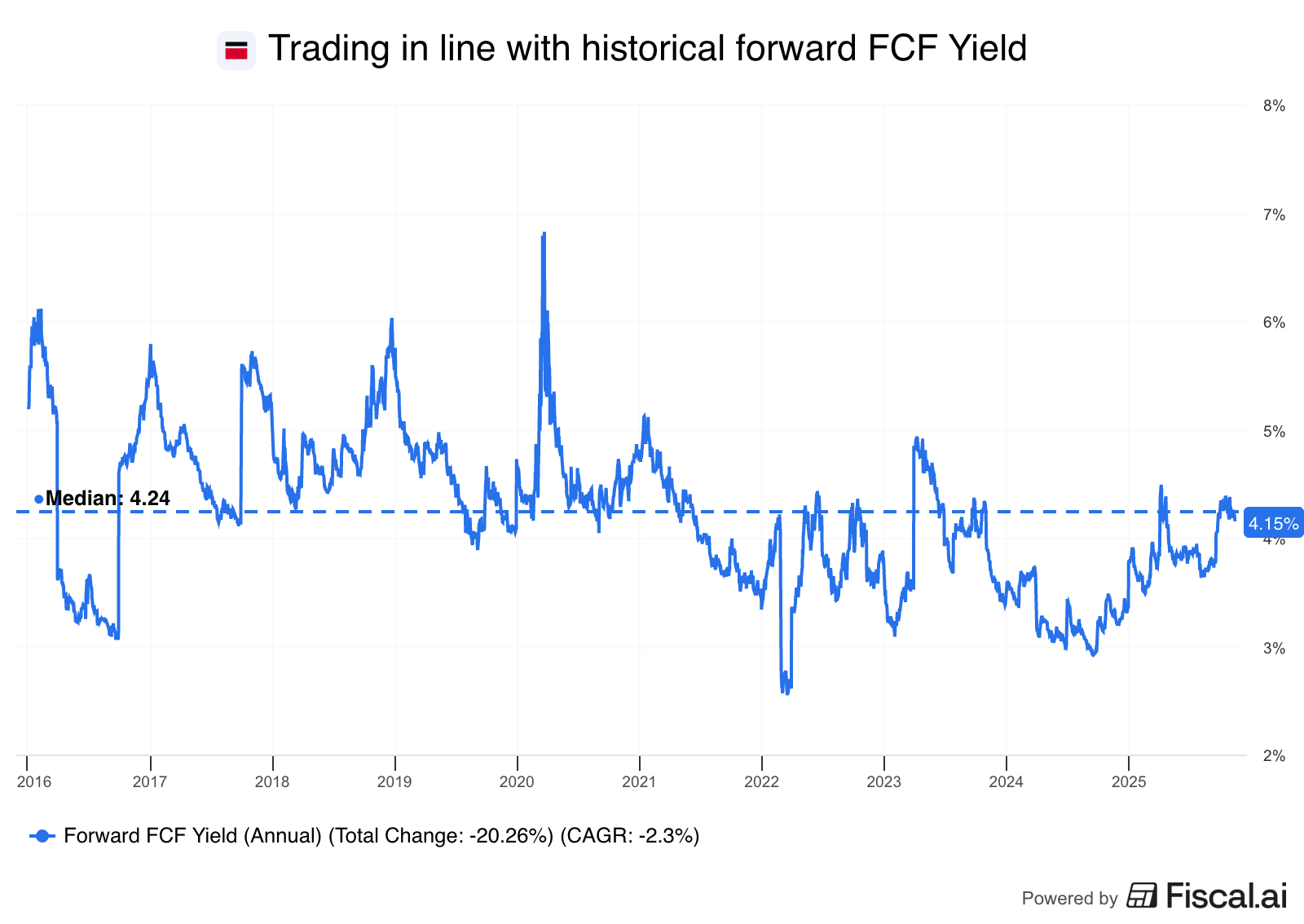

When I first started digging into S&P Global, I was pretty confident it looked like a good deal at today’s prices. A forward FCF yield of around 4% sounded promising. But surprisingly, that’s actually slightly below the average of the last decade. Not exactly the bargain I expected going in.

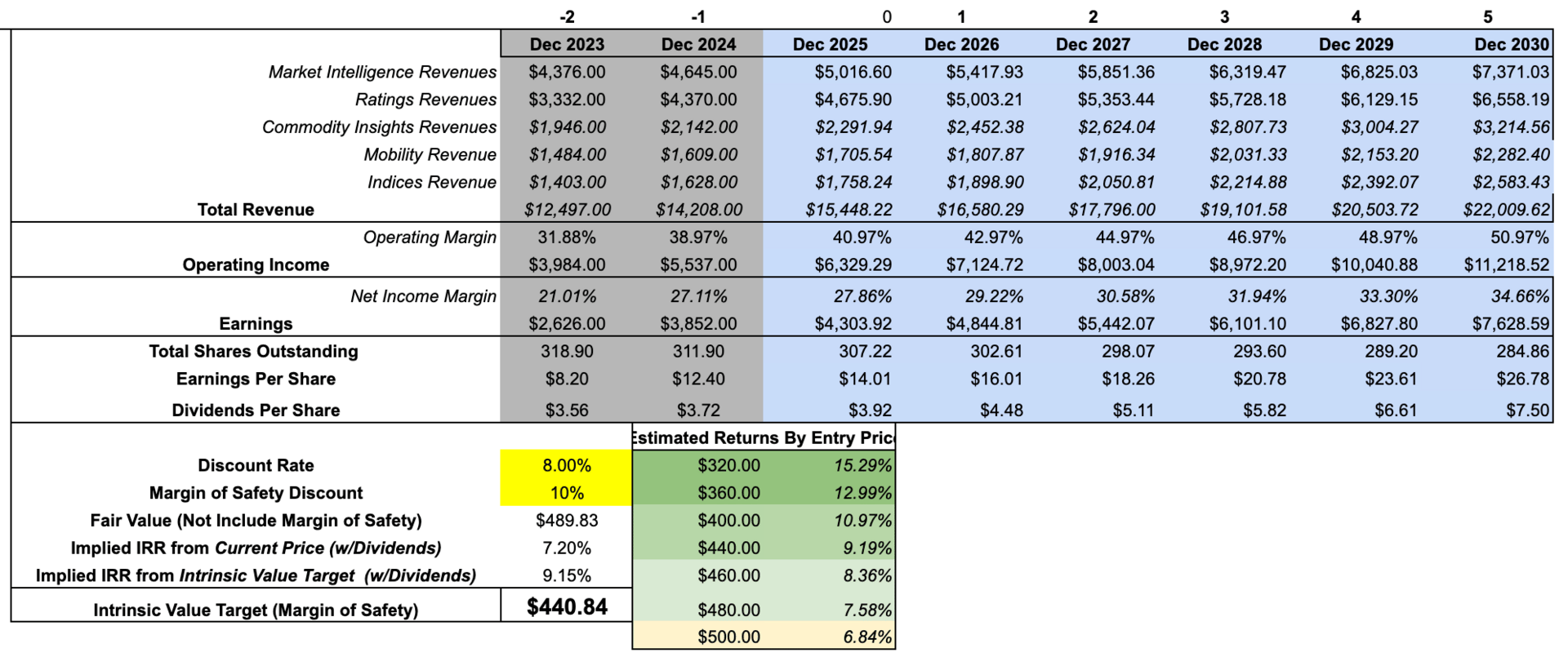

But let’s dig a little deeper and actually run a model. I’m expecting revenue growth of around 7.5% per year — right in line with S&P’s long-term average and consistent with steady mid- to high-single-digit growth across the different segments. Ratings and Market Intelligence should both land in the 7–8% range; Commodity Insights and Mobility a bit lower at 6–7%; and Indices right around 8%.

And since Mobility is still part of the business today, and shareholders would receive shares if it’s spun off, I kept it in the model as well.

Where the real upside could come from is margin recovery. I think it’s completely reasonable to assume operating margins can move from roughly 40% today back toward 50% by the end of the decade. That would come as S&P fully digests the IHS Markit merger, gets more operating leverage from scale, and starts to benefit from efficiency gains through AI across the different segments.

With buybacks in mind, I’m assuming the share count will come down by about 1.5% per year. Using an 8% discount rate, a 10% margin of safety, and an exit multiple of 27x, I get to a fair value of roughly $440 per share.

If you bump the exit multiple to 35x, which is S&P’s trailing P/E, the fair value jumps to around $570. So, long story short, we can predict the company’s earnings and cash flows with a pretty high level of confidence, but the real swing factor here is the multiple you, or the market, are willing to give S&P.

And while I’m confident S&P will remain a high-quality company and, at a minimum, move in line with the market, it’s hard for me to get overly excited about the stock when the main lever is simply what valuation the market decides to place on it.

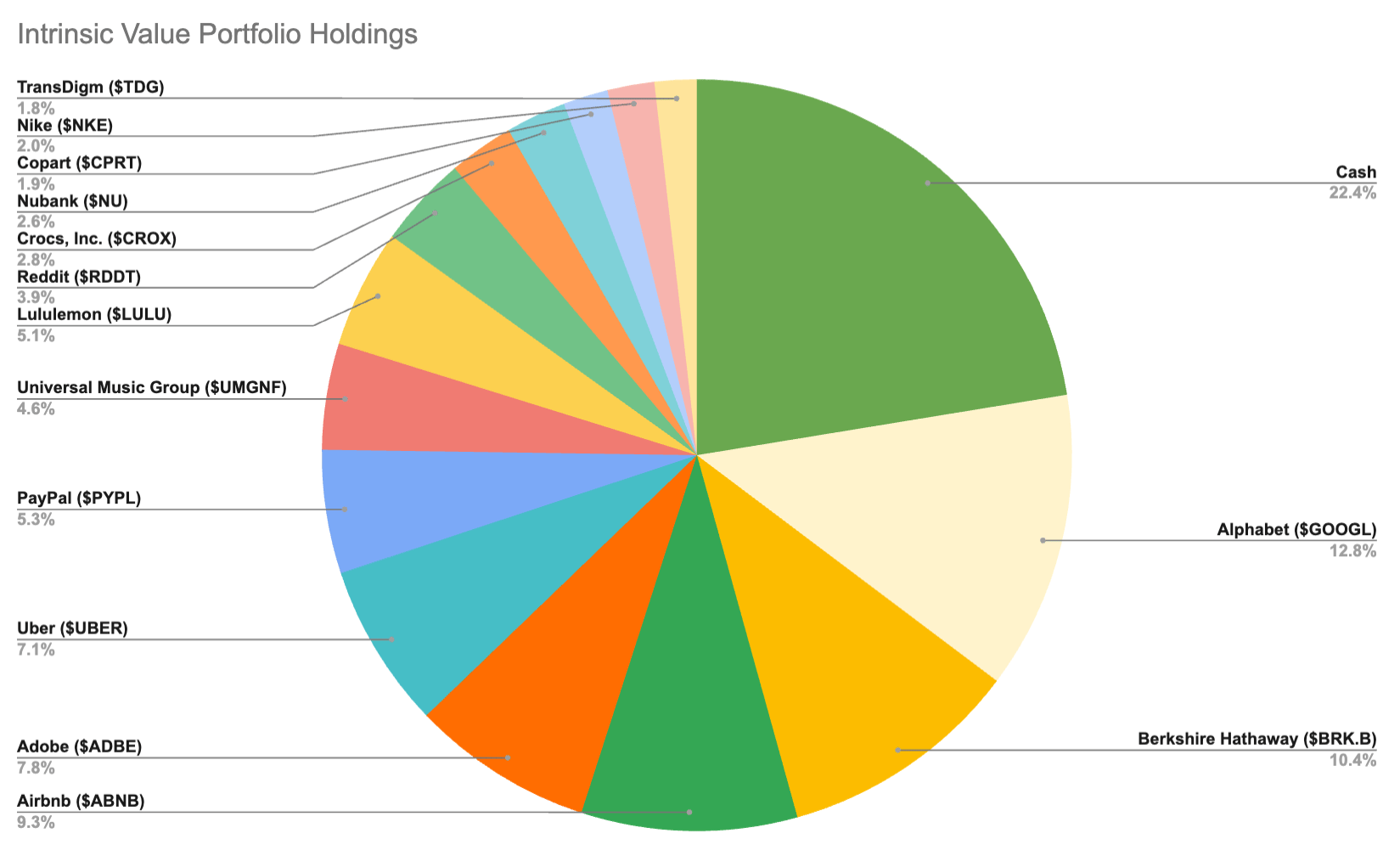

So, this might come as a surprise to you—and it was one for me—but S&P Global hasn't yet been added to our Intrinsic Value Portfolio. It will be at the top of our watchlist, though, and if we see more weakness in the stock, I would love to buy it. And at the right prices, this could easily be a 5% position.

For more on S&P Global, you can listen to our podcast here.

More updates on our Intrinsic Value Portfolio below 👇

Weekly Update: The Intrinsic Value Portfolio

Notes

Well, it has been a quiet week in the markets. After last week’s turbulence, where nerves kicked in, and we saw some red days (not a regular occurrence these days), the dust has settled a bit, and the market has started to “recover.”

For anyone who missed last week’s newsletter, where we announced some portfolio updates, we established a position in Crocs. For the full reasoning, I’d recommend going back to last week’s episode, but we’ll soon release a detailed portfolio update covering performance, holdings, and our broader investment thesis.

Given the risks that Crocs clearly comes with, we wanted to wait for a price that offered a sufficiently large margin of safety. I’m glad we did. When we first covered the stock, it traded close to $100. We entered at $73. Two weeks later, we’re up roughly 15%.

But if there’s one thing I know, it’s that these gains can disappear just as quickly as they appear. The real question is how the next quarters unfold and what they tell us about the durability of the Crocs brand and the potential recovery of HeyDude.

Quote of the Day

"Being a value investor means you look at the downside before looking at the upside.”

— Li Lu

What Else We’re Into

📺 WATCH: Kyle Grieve explains: “How Great Compounders turn Time into a Superpower”

🎧 LISTEN: Interview with Greg Jensen – Co-CIO of Bridgewater

📖 READ: Richard Zeckhauser on Investing in the Unknown and Unknowable

You can also read our archive of past Intrinsic Value breakdowns, in case you’ve missed any, here — we’ve covered companies ranging from Alphabet to Airbnb, AutoZone, Nintendo, John Deere, Coupang, and more!

Do you agree with the investment decision on S&P Global?Comment to elaborate! |

See you next time!

Enjoy reading this newsletter? Forward it to a friend.

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here.

Join the waitlist for our Intrinsic Value Community of investors

Shawn & Daniel use Fiscal.ai for every company they research — use their referral link to get started with a 15% discount!

Use the promo code STOCKS15 at checkout for 15% off our popular course “How To Get Started With Stocks.”

Follow us on Twitter.

Read our full archive of Intrinsic Value Breakdowns here

Keep an eye on your inbox for our newsletters on Sundays. If you have any feedback for us, simply respond to this email or message [email protected].

What did you think of today's newsletter? |

All the best,

© The Investor's Podcast Network content is for educational purposes only. The calculators, videos, recommendations, and general investment ideas are not to be actioned with real money. Contact a professional and certified financial advisor before making any financial decisions. No one at The Investor's Podcast Network are professional money managers or financial advisors. The Investor’s Podcast Network and parent companies that own The Investor’s Podcast Network are not responsible for financial decisions made from using the materials provided in this email or on the website.