- The Intrinsic Value Newsletter

- Posts

- 🎙️ Netflix: Winner of the Streaming Wars

🎙️ Netflix: Winner of the Streaming Wars

[Just 5 minutes to read]

Who says Netflix isn’t a big tech stock anymore?

I don’t care if Netflix got swapped out of the market’s favorite shorthand, ditching Netflix and “FAANG” for the Mag7, because if you strip away the acronyms and just look at what the business is doing, it’s still compounding in a way that would make most companies blush, with operating profits growing 32% a year on average since 2018!

And that’s exactly why Daniel and I wanted to dig in now, because when you see a business like this drop 33% in six months, it reminds us that, even if “everyone knows the company,” that’s not the same thing as “everyone understands the company.”

— Shawn

Netflix: The King of Streaming

In addition to the stock selloff, what piqued my interest in Netflix was also personal, which will come as little surprise to those who know that so many of Daniel's and my stock picks come from our own consumer insights.

For context, I’d been freeloading on my parents’ plan for years, until Netflix cracked down on password sharing, and I ended up in this limbo where I didn’t use it enough to justify paying for it, but I also didn’t want to lose the option value of having it whenever I did want it.

After more than a year, I finally caved. I tried the ad-supported tier for $7.99, because it was cheap enough to justify. But within a few weeks, I upgraded to premium, because, well, ads are annoying(!).

I suspect that illustrates what’s happening broadly with the business right now, with Netflix having entered into a new phase, where it’s less about getting you in the door at any cost (Netflix was happy to kick me off the platform for a period of time) and more about moving you up the ladder once you’re inside. They know that it’s very difficult to resist subscribing to Netflix forever, and at some point, you’ll come back (I did, at least).

So, while subscription counts used to be the obsession, both for Netflix and for the investors watching Netflix, that metric is becoming less and less relevant as the company shifts toward focusing on increasing average revenue per subscriber (ARPU).

By pushing folks to stop password sharing with crackdowns in 2023, they drove a wave of new subscribers to the lowest-priced ad tier initially, with the hope that, over time, ads would grow tiresome, but a Netflix subscription would be too difficult to live without, leading to upgrades to premium (improving ARPU).

At this point in the Netflix story, we know hundreds of millions of people are willing to pay for Netflix monthly at very low rates of churn, and that Netflix has the gravity to suck users back in who got booted during password-sharing crackdowns (such as myself).

So, looking forward, two key drivers of Netflix’s intrinsic value will revolve around how many ad-tier users they can get to go premium, and then, how much further they can raise premium pricing before incurring a significant increase in churn? (I suspect ad-tier users come at more or less breakeven for Netflix, so the profit is in the Premium subs.)

Netflix Today Vs. 2022

The Streaming Wars!

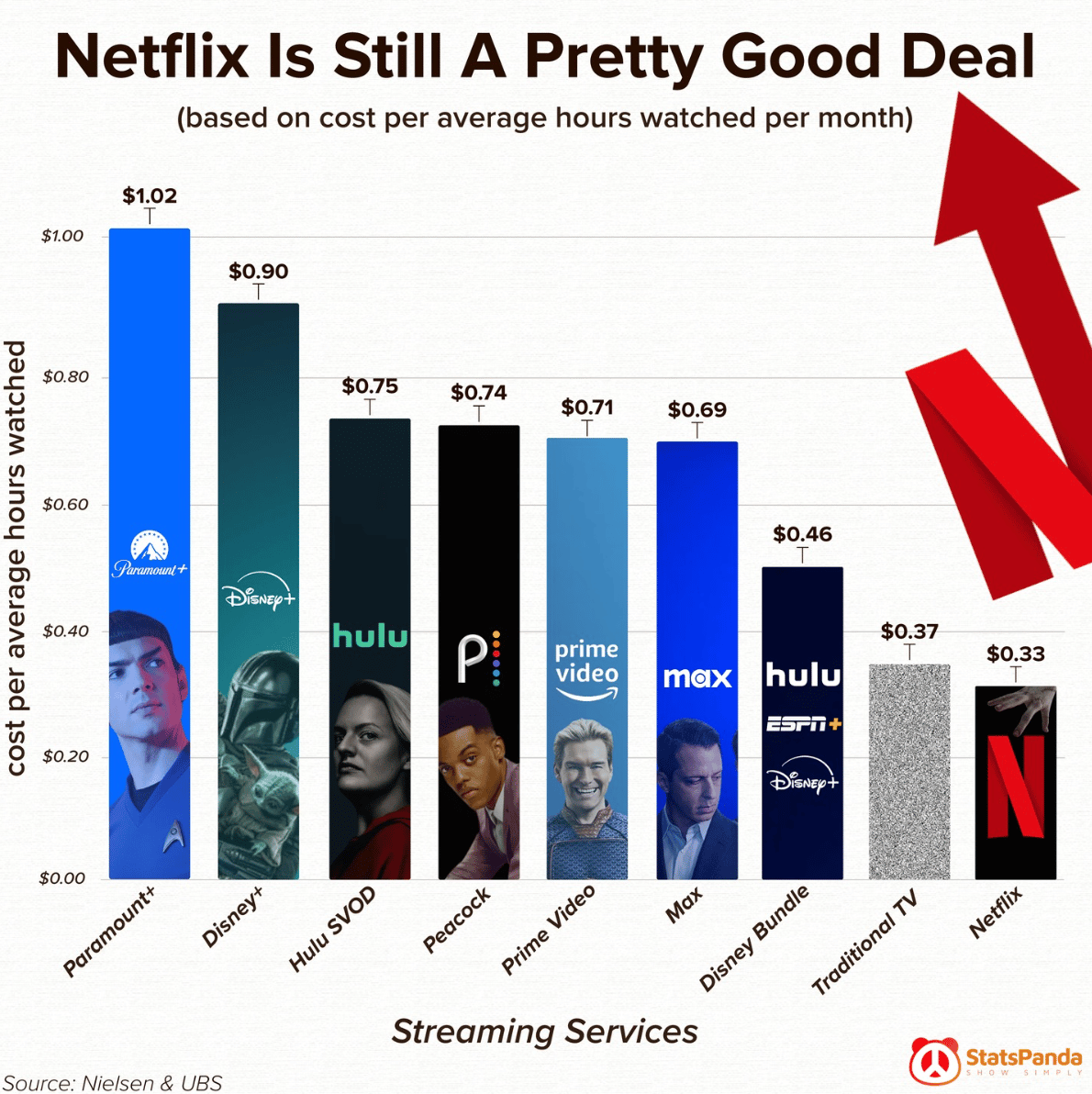

Netflix is increasingly looking less like a fragile subscriber story and more like a robust monetization machine, as it’s moved past the “streaming war” competitive concerns that dominated the narrative in 2022.

In hindsight, we’ve learned that other streaming apps have hardly put a dent in Netflix’s subscriber retention and growth (see the earlier chart above), and so, while the competition still fights to reach scale, Netflix has, in my opinion, signaled that it’s the winner of the first round of the streaming wars by now being able to focus instead on monetization.

And interestingly for us, this is the phase when most of the tangible value creation for shareholders occurs, as free cash flow balloons, even though the market continues to revise down the multiple it’s willing to pay for Netflix’s earnings.

Point being, structurally, there’s a lot less uncertainty around Netflix today than there was compared to 2022, when sentiment last bottomed out over the deleterious effects of new streaming competition, before the business flexed its muscles with password-sharing crackdowns and the rollout of ads while continuing to churn out hit original content.

Spurring the panic in 2022 was the company's first-ever decline in paid subscribers, leading many to conclude that streaming competition was already eroding away Netflix’s excess returns.

Bill Ackman famously bought the stock and then sold out a quarter later over subscriber concerns, which perfectly captures how hard it is to maintain long-term convictions when short-term panics arise, even for the pros. Of course, Netflix didn’t suddenly become a worse business because one quarter’s net adds disappointed, but investors had trained themselves to interpret the business through that single lens, and lenses have consequences if substituted entirely for big-picture thinking.

Retrospectively, Netflix’s shares getting cut in half from the end of 2021 to 2022 in response to one weak quarter (and, to be fair, a selloff in Big Tech across the board), seems like quite the overreaction to what was actually a very normal fluctuation in the business after the Pandemic pulled forward so many paid subscription additions.

A 30-Year Overnight Success

Let’s rewind a bit, though, and appreciate that Netflix is a pre-dot-com bubble company, dating back to 1997. It was a little surprising to me that Netflix is coming up on three decades of existence, because the company still “feels” so young compared to the lingering cable industry it disrupted.

Netflix was early enough to the category that it actually preceded the mainstream-ification of DVDs. They actually had to determine whether mailing discs to customers could even be viable, so they got an early version of the DVD format and mailed it to themselves to see if it would survive transportation and still work. Before that, they tested mailing VHS tapes and realized it was too expensive because of the size and weight, which means the onset of DVDs literally enabled Netflix to exist.

Even in 1998, the ambition was bigger than “mail DVDs,” though, hence the “Net” in the name Netflix. Netflix’s CEO, Reed Hastings, foresaw at-home content consumption becoming digital, and Netflix wanted to be the enabler of that shift — mailing DVDs were always a means to that end.

Jeff Bezos actually offered to buy Netflix in 1998 for $12 million, and, well, Netflix declined because it wanted to partner with Amazon rather than sell. Hastings had taken inspiration to do to Blockbuster what Amazon had done to book stores, so selling to Amazon at that price would’ve been a capitulation of his dream before it had even begun to be realized.

Then the dot-com bubble happened. Netflix had raised about $150 million, fortunately, but the business wasn’t yet profitable, and management became concerned about whether they’d ever be able to raise funding again before bankruptcy set in. So they swallowed their pride and took another swing at selling the company, this time to Blockbuster, for $50 million. Blockbuster declined because they thought they could instead let a competitor shrivel up and die. Yes, Blockbuster passed on buying Netflix.

Netflix did, of course, not shrivel up and die.

The company survived by showing its killer instinct, cutting 40% of the company’s employees overnight. Not 5%. Not 10% over six months. 40% overnight!

By 2002, despite the tech market still being in rough shape, Netflix raised another $82 million as a lifeline, but at an enormous cost, selling around a quarter’s worth of the company’s equity to investors. And then from there, we got the version of Netflix most people remember, the one that scaled from a DVD-by-mail business into a streaming behemoth.

Netflix Isn’t Fighting Disney; It’s Fighting Your Remote

Most people define Netflix’s competitive set as other streaming apps, and that’s true in a narrow sense. Disney+ and Hulu compete for subscription dollars, HBO Max competes for premium scripted series, and Prime Video competes because Amazon can subsidize content economics in a way no pure-play streamer can.

But Netflix’s internal competitive framework is broader and, frankly, more honest.

They don’t benchmark themselves against streaming services alone. They benchmark themselves against everything that can steer a person’s leisure time away from Netflix, including linear TV, user-generated content on YouTube, video games, and social media. So their strategy is less about “beating Disney+” and more about winning the specific moments when someone decides what to do with the next hour of their life.

Management refers to those as “moments of truth,” which I love as a phrase because it forces you into the most realistic version of competition. Not who has the best catalog in the abstract, but who wins when the consumer’s thumb is hovering over a remote, a phone, or a controller.

Incredibly, despite Netflix’s cultural footprint, its share of total TV viewing time remains under 10% in every country it operates in.

Even in markets where Netflix feels ubiquitous, the majority of leisure time is still dominated by everything else, especially linear TV and non-Netflix entertainment.

Cable has persisted longer than some would’ve guessed, but as the number of hours devoted to cable TV continues to decline, a chunk of that consumption will continue to flow to Netflix, increasing Netflix’s share of total viewing hours over time.

This is why, when people talk about streaming wars like they’re trench warfare where everyone gets destroyed, I’m inclined to say Netflix has already won the first era of the war, and everyone else is fighting for second place. Netflix is playing for the largest prize — global free time, not just a slice of the subscription pie.

Netflix’s leadership has been explicit about what the real engine is: engagement.

If members are deeply engaged, retention improves because the service feels valuable, and customer acquisition improves because satisfied members promote Netflix via word-of-mouth conversations about its content. Thus, strong engagement enables Netflix to spend less to retain & acquire subscribers than the competition through paid marketing, allowing them to reinvest more in content and in the effectiveness of their suggestion algorithm, spinning the flywheel faster.

Competitors Become Suppliers

Netflix started as an intermediary distributing other creators’ content, and then the next big shift was producing its own content, which, honestly, we probably would’ve criticized at the time for being outside its circle of competence as a software company.

Fortunately, Netflix didn’t let critics rein in their plans, and they defied the odds, becoming as big a player in Hollywood and other global hubs for cinema as anyone.

And now, they have this unique blend of popular original content, available only on Netflix, with shows and movies licensed from other media businesses, too.

Beyond the significant cost of trying to create all of their own content, licensed content has been something of a strategic weapon for Netflix.

The show Suits is a great example. It was a “second-run” show, but it suddenly became a monster hit on Netflix long after its original airing. The lesson isn’t that Netflix got lucky but that Netflix has shown it can take an already-proven asset, license it at a fraction of the cost of producing a new original, and still generate enormous engagement.

I attribute this largely to Netflix having the best algorithm, thanks to years of being the #1 player in the industry, providing them with ample user data.

Breakdown of media & streaming consumption

I find myself doing this, but I’m sure many can relate to the idea — I often open Netflix to have it “tell me” what to watch, because the algorithm is so effectively personalized. Whereas with other streaming apps, I largely open them when I have specific shows in mind to watch (or as a backup if I really can’t find anything on Netflix).

That trust in the Netflix algorithm is why Netflix is able to take content from other platforms and breathe new life into it among its subscriber base.

And because the Netflix model is built around delivering enough value per dollar of content spend, the question is never solely about choosing between “original or licensed” content in the abstract. The question for Netflix is “what engagement does this content generate relative to what we spend?”

If you can buy engagement more efficiently through licensing than through originals, you do it. It strengthens the member proposition and improves the return on capital tied up in content.

The even more interesting question is whether competitors are cannibalizing themselves by licensing shows to Netflix in exchange for a few dollars today. If your competitors aren’t as scaled and are desperate to prove profitability to their own shareholders, the incentives can go awry. Back catalogs become a funding source, yet competitors undermine themselves by becoming suppliers to Netflix.

Local Content, Not Hollywood Exports

Netflix is sometimes framed as an American platform expanding outward, and I understand why people think that, because the most visible hits early on were English-language and Hollywood-adjacent. But the company’s actual playbook is local-first. They aim to make great local content everywhere, with the hope that the best stories will travel.

This matters because it’s the only way to truly compete for free time in over 190 countries. Exporting Hollywood is a limited tactic, but an archive of authentic programming for local markets at scale is a recipe for global entertainment dominance.

Squid Games makes the point pretty well. It wasn’t engineered as a global blockbuster in the way the industry typically thinks about blockbusters. It was created first for Korean viewers, and then it reached the rest of the world because authenticity travels better than generic globalized storytelling. It would’ve been unfathomable, years ago, to think that audiences globally would happily sit through a series dubbed in another language or with closed captions, and yet, that’s exactly what Netflix proved with Squid Games.

This was not by accident, because Netflix has invested heavily in subtitling and dubbing. They subtitle and dub in dozens of languages, and something like 97% of subscribers have now watched a non-English language title at least once.

From an intrinsic value standpoint, high-quality translation increases the reach and shelf life of each piece of content. Once you spend $20 million or $30 million on a movie, you want to maximize global viewing, and language accessibility becomes a force multiplier.

This is also where Netflix starts looking like a tech company again. Distribution, personalization, translation workflows, all of that scales differently than a traditional studio model, and Netflix has built systems that make the global flywheel spin faster.

Netflix’s unit economics did shift, though, when it moved into original content production because originals are cash-intensive upfront, whereas licensing is less capital-intensive since you’re not funding development years ahead.

But licensing means you don’t own the IP, and you don’t control the rights. That’s why Netflix thinks about content in terms of efficiency ratios and also halo effects (where a title becomes a cultural moment that drives acquisition).

And this is one of my favorite insights from studying Netflix. Content creation is part of their marketing budget.

Historically, marketing costs in entertainment have been variable, but Netflix has turned much of that into a fixed cost by using the platform itself as the marketing channel, surfacing titles based on your behavior and preferences when you open the app. Point being, if you own the content and the distribution, as Netflix does, you can reduce customer acquisition costs in ways competitors struggle to replicate.

Netflix “Just Works”

Daniel pointed out something to me that may be obvious as a user but is easy to overlook as an investor: Netflix just works. Outside of a handful of botched live events where tens of millions of people were watching simultaneously, Netflix tends to perform better than other streaming apps. It loads faster, crashes less, has more accurate closed captioning, and has a more intuitive interface.

There are real business decisions underlying that.

Netflix embraced cloud computing early, migrating infrastructure and compute to AWS over what was a painful seven-year process. That matters because personalization and recommendations become more compute-intensive over time, and cloud-native architecture positions Netflix to scale those capabilities.

On top of that, Netflix built and operates its own content delivery network called Open Connect. It’s a proprietary CDN that helps internet service providers localize and manage Netflix traffic, improving streaming quality and consistency. About 17,000 servers are deployed across nearly every country, and that infrastructure helps explain why Netflix “just works” more reliably than other apps!

In a way, Netflix is like a restaurant, and restaurants aren’t just about the food.

People go for the hospitality, the service, and the atmosphere. In the same way, Netflix isn’t only the content. The app experience is part of the product, and Netflix has made the viewing experience easy, intuitive, vivid, and consistent enough that the user experience itself becomes a driver of loyalty. Again, that’s why an old show like Suits can be a hit for Netflix and less so for other platforms — being on Netflix often makes a show popular (or popular again), but not vice versa.

That, to me, is a moat.

Capital Intensity

The elephant in the room is that Netflix is capital-intensive, which, until the Mag7 started dumping hundreds of billions into AI data centers, was a real limiting factor in Netflix’s appeal to investors comparatively.

Producing localized hit content in India, Japan, Colombia, France, the UK, and everywhere else is expensive. This isn’t a software tool like Microsoft Excel, where the product can easily scale globally, allowing margins to explode with little incremental cost.

And so, for years, one of the most common critiques of Netflix was the balance sheet & cash flow statement. Too much debt. Too much cash burn. Too much negative free cash flow. And the critique always sounded damning because investors treated negative free cash flow like a character flaw rather than like a strategic choice to invest in the company’s moat.

Original content requires upfront cash long before payoff arrives, which is why Netflix had a substantial drag on free cash flow for years.

But you’re spending on something that generates value across years of member engagement. It’s like Universal Music Group, where the core model is betting on artist talent, funding production and touring, and then profiting off royalties for decades.

TV shows and movies are different because they’re replayed less than songs, but the consumption time is longer, and some content becomes timeless anyway, creating assets with effectively indefinite lifetimes. Plus, hit content can always be revitalized by the next generation, so there’s some enduring optionality. People still love to watch the original Star Wars!

The reason this matters is that Netflix is now on the other side of that investment cycle, meaning that operating leverage can kick in, since content spending doesn’t have to scale 1:1 with subscriber growth. A large investment needed to be made to significantly diversify Netflix’s content to appeal to a wider base, but now, Netflix has the content to satisfy a more global audience without the same need for incremental content reinvestment, leaving room for margins to expand.

See for yourself:

On that note, I should mention that Netflix is doing roughly $39 billion in revenue, with a global ARPU of $11.64, which breaks out to a U.S./Canada ARPU of around $17.20, and an Asia Pacific ARPU of around $7.30.

We can deconstruct things further, though, to get a better look into Netflix’s operating profits: With content amortization costs of around $22 billion, that’s roughly 50% of revenue, down from ~60% a few years ago. Marketing expenses come in at $3 billion, about 8% of revenue, while tech and development costs are another $3 billion. Then, overhead is 4.5% of revenue, leaving Netflix with an operating profit margin nearing 30%.

You will notice that, as the business has matured, the gap between free cash flow and operating profit has narrowed, as past investments in content pay off over time.

This is why I think the “Netflix is just a capital-intensive studio” framing is incomplete. Studios don’t have this kind of recurring revenue base. Studios don’t have this kind of direct-to-consumer distribution. Studios don’t have this kind of data feedback loop. Netflix is a hybrid, and hybrids can be misunderstood, which is exactly why they sometimes get mispriced.

The Warner Bros Question

Before we get to valuation, we have to talk about the company’s proposed acquisition of Warner Bros.

For context, there are two competing offers, one from Netflix and one from Paramount Skydance. Netflix offered to pay $27.75 per share of Warner Bros, with $23.25 in cash and $4.50 paid in Netflix stock.

That implies an enterprise value of roughly $82 billion, including debt, which values Warner Bros’ equity at ~$72 billion. Netflix, though, isn’t offering to buy all of Warner Bros. Netflix would take the crown jewels, meaning the studios and streaming assets, while leaving behind some of the legacy linear television assets that are structurally declining and complicating.

As a result of the Netflix deal, Warner Bros. shareholders would get A) $27.75 in cash, B) approximately $4.50 of Netflix stock, and C) shares in a spinoff company founded with the company’s remaining assets, including CNN, TNT, Discover+, and Bleacher Report.

But Paramount wants to buy all of Warner Bros., and is offering $30 per share in cash. It’s a cleaner deal, but long story short, Warner Bros. is worth 5x as much as Paramount, which would be a gargantuan deal for them to digest, so there are concerns that they might not be “good for the money.” Netflix, on the other hand, is unequivocally good for the money.

The story is made messier by the fact that Paramount is run by David Ellison, the son of one of the world’s richest men, Larry Ellison (founder of Oracle), who is offering to personally backstop the deal’s financing for Paramount. There’s also a web of political connections that seemingly position Paramount to be the likelier candidate to pass regulatory scrutiny, but nonetheless, the Warner Bros. board is recommending that shareholders accept the Netflix offer.

It’ll be 12-18 months before we have any resolution on this, but from Netflix’s perspective, I’d imagine they see this as a once-in-a-generation opportunity to snap up another media giant’s assets, providing them with a deeper content library and iconic IP.

To be clear, Netflix doesn’t need a deal like this to win. They are already winning. The question is whether the incremental value of content ownership and IP is worth the distraction and risk, and on that point, I’m not sure.

If Netflix can cherry-pick assets that make the platform stronger without inheriting a pile of declining legacy baggage and debt, I can see the strategic appeal. I’d probably be a bit relieved if the deal didn’t go through (though a Netflix + HBO streaming bundle would be awesome!), but I’m also inclined to say that Netflix’s co-CEOs, Greg Peters and Ted Sarandos, have proven themselves as being more than capable capital allocators who, I’m sure, are well aware of the disastrous history of media mega mergers.

It’s the weakest point in my bullish thesis for the business long-term, but I’m inclined to give management the benefit of the doubt. My concern, then, is less that the current deal offer is value destructive, but that the company will get carried away in a bidding war with Paramount for Warner Bros. that takes the acquisition price meaningfully higher.

Valuation, And The Discipline Of Waiting

With all that said, since the deal is far from a guarantee at this point, I focused on modeling Netflix’s earnings without accounting for the Warner Bros. acquisition for the sake of simplicity.

As such, I modeled earnings per share growth into the second half of the decade, discounted those earnings back at an 8% rate, and used three different terminal multiples depending on the base (30x earnings), bull (34.5x), and bear cases (23x). I also layered in a 30% margin of safety to reflect uncertainty stemming from the Warner Bros. deal.

Assuming some continued room for operating leverage in the base and bull cases, with revenue growth ranging between an average of 9.5% a year and 11.5%, respectively, I landed on a fair value estimate of between $100 per share (base case) and $140 per share (bull case, clearly).

In a bear case, it’s hard for me to plausibly imagine revenues actually declining, but I could see the revenue CAGR decelerating significantly to, say, 5% over the next five years if competition begins to weigh on Netflix’s business. That could also mean modest declines in margins as Netflix spends more again on content to remain competitive, though some of the downside is reduced by the fact that Netflix has been aggressive about repurchasing shares in recent years (spending 16-18.5% of sales on buybacks annually between 2023-2025).

If, in a bear case, growth falls off, the stock would surely be punished, but each dollar of buybacks would go further in shrinking the share count if made at lower prices, helping to support earnings per share growth by reducing the denominator in that calculation.

So anyways, I hedge the bear case a bit, but if the bear case proves true, I could imagine Netflix’s fair value today being below $50 per share.

And since we don’t know which version is most likely to match reality, I estimated a blended fair value that assumes a 50% likelihood of reality approximating my base case, 30% for the bull case (showing my bullish bias), and 20% for the bear case, suggesting a fair value overall of about $100 per share today.

But I mentioned wanting a 30% margin of safety to feel comfortable with the investment — for the risk/return profile to match our hurdle rate, and so, a target intrinsic value entry price for Daniel and me would be between $70 and $75.

We weren’t actually expecting to add Netflix to the Portfolio this week, but on Thursday, we got a 6% slide to ~$75 in the stock that put the shares down 40% in the last six months. An ideal entry price would be closer to $70, but with a long-term perspective in mind, we’re content with opening a full 5% position in Netflix (best not to be too greedy when the margin of safety is already reasonably wide!).

We tend to record the podcasts a week or two earlier, so we actually put the stock at the top of our watch list in the episode, only for it to become sufficiently more attractive in the meantime, leading to the decision pivot in the newsletter here.

The market may very well continue to drag Netflix down in the short-term, or the S&P could spike again, and we don’t know (nor does anyone else) what will come next, but if you zoom out enough, we suspect this will prove to approximately be a very attractive entry price.

Updates on the rest of our Intrinsic Value Portfolio holdings below!

Weekly Update: The Intrinsic Value Portfolio

Notes

This past week, for members of our Intrinsic Value Community, we had the pleasure of hosting two excellent guest speakers: Drew Cohen of Speedwell Research and Adam Seessel, author of Where The Money Is: Value Investing In The Digital Age. Members had the chance to chat with both of them directly for 90 minutes or so, and I have to say, both were very inspiring. Adam Seessel’s wisdom was particularly impactful.

Adam helped solidify a distinction in my head that I think is very timely: Owning monopolies is great, but there are monopolies that are solely “milking” (his words) their positioning, while others use their monopoly positioning to aggressively reinvest and to expand their dominance into new areas. In the latter camp belong titans like Alphabet and Amazon (his only two “tech” holdings), who’ve used profits from Search and E-Commerce, respectively, to expand into streaming (YouTube), cloud computing, quantum computing, and more. Adobe and Apple come to mind as examples of the former. Apple especially has milked a lot out of the iPhone, but has very little to show for it, in terms of business diversification.

That’s not to say we’re interested in exiting our Adobe position (we don’t own Apple) — Adobe is one of our largest bets, but we did walk away from the call particularly excited about Amazon.

Amazon: Correspondingly, with Amazon down about 20% in the last month at the time of our purchase on Thursday, we felt the company had finally reached a level of sufficient attractiveness to warrant a full 5% position in the Portfolio.

Nike: If you’re keeping tabs at home, we’ve used up 10% of the cash in our portfolio in one week by starting positions in Amazon and Netflix! To fund these moves and keep a bit of cash ready on the sidelines for future opportunities, we opted to close our Nike position. Overall, we made a 9% return on it.

Why did we exit? For no specific reason other than that, of all our portfolio holdings, Nike was the one we were least excited about going forward and had the lowest relative conviction in, so we decided we’d rather sell it down from a 2% portfolio holding and liquidate into cash.

Berkshire: Unfortunately, Nike’s relatively small position didn’t satiate all of our cash needs to invest in businesses we’re more excited about (NFLX/AMZN), and so, we opted to trim Berkshire from almost 11% of our portfolio to below 8%.

Again, you may be asking why? Well, since we first invested in Berkshire, we’ve treated it as a placeholder position. It’s a reasonably stable (and fairly valued) source of funding to tap into when opportunities arise, as we’ve identified with Netflix and Amazon. You might argue, then, that we should sell more of the Berkshire position, but that would free up more cash than we currently need. Plus, we all have our biases, and for better or worse, we sleep better at night knowing we own a piece of Berkshire.

Crocs: One last change! On Thursday, after reporting earnings and continuing to buyback their own stock hand over fist, Crocs jumped over 20% intraday! With our Crocs position up ~35% for us, we felt this made for convenient timing to lock in some gains and free up more cash to be used opportunistically. Yet, the thesis is very much working out as hoped, so exiting the position entirely now would likely be premature. As such, we agreed to cut the position in half. Long-term, we’re not thrilled to be in retail companies, so we hope to further whittle down this holding over time.

We’re just an email away ([email protected]) if you have any questions or comments on these moves :)

Quote of the Day

“Most entrepreneurial ideas will sound crazy, stupid, and uneconomic, and then they'll turn out to be right.”

— Former Netflix CEO, Reed Hastings

What Else We’re Into

📺 WATCH: How a single Costco changes its local economy

🎧 LISTEN: The Story of Uber with Clay Finck

📖 READ: How Warren Buffett’s Geico fell behind Progressive in the auto insurance race, article by Adam Seessel

You can also read our archive of past Intrinsic Value breakdowns, in case you’ve missed any, here — we’ve covered companies ranging from Alphabet to FICO, Transdigm, Lululemon, PayPal, DoorDash, Crocs, LVMH, Uber, and more!

Your Thoughts

Do you agree with the portfolio decision for Netflix?(Add a comment after submitting to elaborate!) |

See you next time!

Enjoy reading this newsletter? Forward it to a friend.

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here.

Join the waitlist for our Intrinsic Value Community of investors

Learn how to join us in Omaha for the 2026 Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meeting!

Shawn & Daniel use Fiscal.ai for every company they research — use their referral link to get started with a 15% discount!

Use the promo code STOCKS15 at checkout for 15% off our popular course “How To Get Started With Stocks.”

Read our full archive of Intrinsic Value Breakdowns here

Keep an eye on your inbox for our newsletters on Sundays. If you have any feedback for us, simply respond to this email or message [email protected].

What did you think of today's newsletter? |

All the best,

© The Investor's Podcast Network content is for educational purposes only. The calculators, videos, recommendations, and general investment ideas are not to be actioned with real money. Contact a professional and certified financial advisor before making any financial decisions. No one at The Investor's Podcast Network are professional money managers or financial advisors. The Investor’s Podcast Network and parent companies that own The Investor’s Podcast Network are not responsible for financial decisions made from using the materials provided in this email or on the website.